- Home

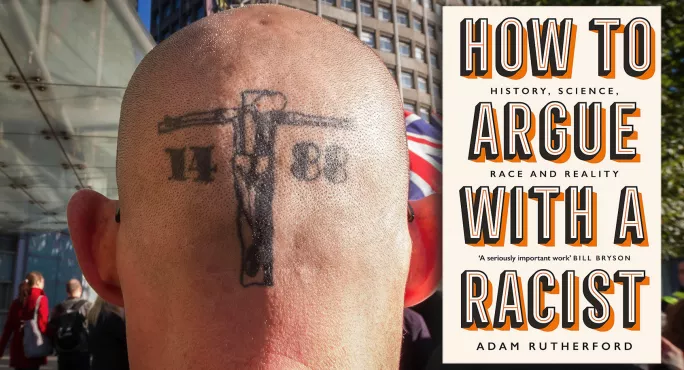

- Book review: How to Argue with a Racist

Book review: How to Argue with a Racist

How to Argue with a Racist: History, Science, Race and Reality

Publisher: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

Author: Adam Rutherford

Details: 224pp, £12.99

ISBN: 978-1474611244

This is a great addition to existing work on how ideas of “race” and racism affect our society.

Scientist Adam Rutherford argues, as many others have done before him, that the general scientific accepted viewpoint is that “race”, a category detailing human differences based on physical differences, actually has no basis in science.

I think it bears repeating.

“Race”, the idea that people of different skin colours are distinct fundamental biological groups with related behaviours, doesn’t exist from a scientific point of view.

We emanated from our ancestors leaving the area that we now call Africa over 70,000 years ago. But that is pre-history, and we find it difficult to get our heads around.

This is where Rutherford drops an apparently simple truth: if we use logic and maths, we can see that our relatedness as a species is also closer than we think and it starts with the metaphor we use to think about families.

Family trees

When we usually think about family trees, we can maybe go a few generations back, creating an image that our families are distinct. Your parents - two ancestors.

Their parents (your grandparents) - four additional ancestors. The parents of the grandparents, eight additional ancestors. The discipline of genetics assumes that a generation is around 30 years and in each generation further back in time, the number of your ancestors doubles.

Over a 500-year period, your ancestors would number 1,048,576. A thousand years ago, around the time of King Cnut, your ancestors would number over a trillion people. This sounds incredible, especially when we consider that there are more people alive now than have existed at any other time.

How can our family tree be so large and distinctive? The issue is that rather than positions in each branch being unique to our own families, there are ancestors who occupy positions in the branches of other families.

This is where the metaphor of a distinct family tree breaks down, because rather than a unique individual and separate system, your ancestors are my ancestors, and not because of the accepted scientific fact that Homo sapiens originated from Africa.

Rutherford suggests that if you could draw a perfect family tree for all Europeans, at least one branch of that family tree would pass through a single person who lived in the 1400s. Going further back in time and we reach the mathematical certainty of the genetic isopoint; a point in history where all the people alive at the time are the ancestors of everyone living today.

This is not at the Stone Age, which may fit popular conceptions, but the time of the Egyptians, the Hittites and the Shang Dynasty in the 14th-century BCE.

Simplifying complex science

Alongside this history lesson, Rutherford also deconstructs the notion of skin colour (not binary as we like to describe people as “black” or “white”), how genes work, or, most importantly, how they do not work and how there is more genetic diversity between Africans than between Africans and anyone else in the world.

Rutherford makes the point starkly: there is more genetic difference between two San people from different groups in southern Africa than between them, a Briton, a Sri Lankan and a Māori.

What makes Rutherford’s short book brilliant is that it explains the very difficult and complicated science around genetics in easily understood terms.

I’ve used the notion of the genetic isopoint with history students and, although disbelieving, someone usually works out the maths and says that to go against this idea would be like believing in fairy tales.

Yet, this is the issue. Rutherford is fantastic at explaining why the apparent scientific rationale behind race thinking and racism is just not true, but we, as a society, and as educators, are currently locked within, and actively maintain, racial ways of thinking.

Sensible debates

Racial thinking and racism are more than just science, they have social power and status, too.

Rutherford’s hope is that the book should be a weapon, written to, “equip you with the scientific tools necessary to tackle questions on race, genes and ancestry. It is a toolkit to help separate fact from myth in understanding how we are similar and how we are different”.

It is undoubtedly useful if you are struggling to understand the science, but its faith in rationality, that we can engage in productive arguments with racists, is bound to fail.

This is why How to Argue with A Racist is such an interesting title, because when trying to engage in real-time with someone who is racist, it is likely to result in insults on Twitter, being dismissed as being woke or even being shot and killed while going out for a jog.

Beyond the confines of the book, debating can be a dangerous, even deadly, business. Simply put, arguing with a racist, particularly if you are representing the object of their racism, can be a very bad idea.

Self-reflection

However, I think Rutherford’s title is meant to relate the dialogue we should have with ourselves.

We live in one of the most liberal democratic states and education systems in the world, but we remain very much tied to racial thinking.

Some curriculum thinkers point out the need to ensure that we keep dead, white men on the curriculum, maintaining racial ways of thinking about ideas and humanity. We reach for racial explanations when discussing the IQ scores of different groups identified by skin colour, justifying educational approaches that seem to work only for certain groups and not for others.

We give explanations, as the sprinter Michael Johnson did, that the reason why certain sports and cultural activities are dominated by certain groups is down to biology.

The current crisis has revealed the issue of racial thinking in stark terms. The number of deaths due to Covid-19 in minority ethnic groups has led some to reason that genetic difference reflected in skin colour is to blame.

This ignores the fact that certain ethnic groups, owing to economic, social and historical factors, are in jobs that increase their exposure to the virus and limit their ability to work from home.

Racism and racial thinking is not just a problem for overt racists. It is a problem for us all as we use it to orient our thinking about the world we live in.

Society and science

Rutherford’s book, within this context, should be seen as an important element in the discussions we are going through internally around the types of societies we want to live in and the type of education systems we want to provide.

It should become part and parcel of our thinking about our classrooms, curricula and organisational cultures because, for all our belief about science and research informing schools, we still use the language and notion of “race” to make sense of our society and its institutions.

In a world where many of us accept that memory is the residue of thought, our continued racialised imaginary serves to legitimise racism in education and society despite the scientific evidence proving otherwise.

Rutherford provides a timely reminder that while science can offer many answers, it cannot by itself, resolve social issues.

That change, unsurprisingly, is down to us.

Nick Dennis is director of studies at St Francis’ College, Hertfordshire. He tweets @nickdennis

You can support us by clicking the book’s title link: we may earn a commission from Amazon on any purchase you make, at no extra cost to you

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters