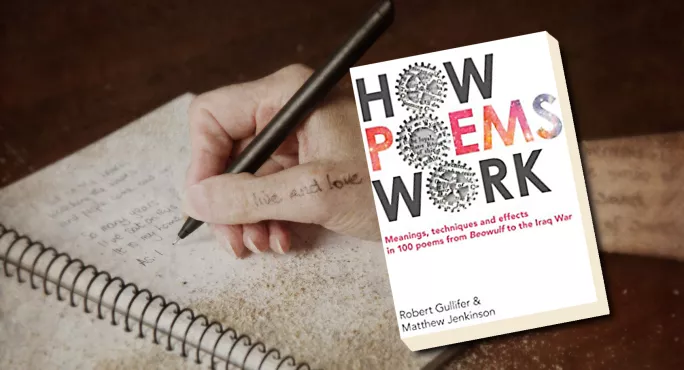

Authors: Robert Gullifer and Matthew Jenkinson

Publisher: John Catt Educational

Details: 303pp, £18, paperback

ISBN: 9781911382942

If you have seen Dead Poets Society, you will be able to recall the notorious “Rip it out!” scene, in which teacher John Keating encourages his students to remove the introduction to their poetry anthology. This scene popularised a long academic debate about a poem’s meaning: do we need to know the devices and the authorial intent to understand poetry effectively?

If you are a student or an English teacher, the simple answer is yes. In the context of the current curriculum, every word is for a reason, every writer has intent, and every device must be identified and explored. Yet, if it were to be discussed, it’s easy to think of many writers who would sit on the opposing side. Both Oscar Wilde’s art-for-art’s-sake preface in the opening of The Picture of Dorian Gray and Roland Barthes’ claims in The Death of the Author support the view that a poem’s meaning exists in the imagination of the responder and not the knowledge of the writer; a text’s unity lies not in its origin, but solely in its destination.

The recent publication by Robert Gullifer and Matthew Jenkinson, How Poems Work: Meaning, Techniques and Effects in 100 Poems from Beowulf to the Iraq War, brings this debate back into the spotlight. In their introduction to the book, the authors assert nicely that perhaps “the way poetry works” is not important, nor does it have to be explained. So why have they published a book with such a title?

Gullifer and Jenkinson argue that there is immeasurable value in learning about poetry - whether you are a general reader, teacher or student. The anthology addresses the debate with an effective objectivity, providing readers with an array of timeless poetry, as well as a brief analysis of both writer’s context and easily identifiable poetic devices.

The collection of poetry chosen for this edition is undoubtedly canonistic. The authors have selected an assortment of foundational British poetry, so the appearances of names such as Shelley, Kipling, Yeats, Tennyson, Rossetti and Browning should not come as a surprise to many; of course, one cannot argue the historical influence that these writers have had over the genre of poetry. As the content moves chronologically towards more modern publications, it is nice to see that the authors have widened their poetic spectrum to poets such as Carol Ann Duffy, Grace Nichols and Paul Muldoon.

Gullifer and Jenkinson justify the simple tone and briefness of the information they have provided; the book aims to present a taster of the historical and progressive climate of poetry. The result is twofold: if the reader is familiar with the poem, the information may become frustratingly oversimplified; if the reader is not, the information is an encouraging and accessible starting point.

Regardless, there is undoubtedly a lot to gain from this edition. Not only does it provide a collection that is arguably the “must know” of poetry, it draws nicely on key images, zooms into devices (both literary and structural), and has an easy-to-read format with emboldened terminology. At the front of the text, the authors have also developed a table to assist their readers in re-accessing the terms used. They have provided a definition for each keyword and the authors remind us of the poems they appear in; a useful tool that could spark endless discussion in the classroom or among friends. While it may have been wise for Gullifer and Jenkinson to make explicit that the poems are not limited to the devices they have identified, an engaged reader will deduce this, as they explore the collection.

However, the authors’ claim to challenge the “tweedy” image of literature is not entirely achieved and they seem to suggest that the British canon is “worthwhile” literature - a point challenged by various other modern or cultural anthologies. The choice to include only one-fifth female writers does suggest a somewhat archaic and traditional approach to the concept of valuable literature; some may argue it is slightly pedestrian.

If the aim of both authors was to challenge the canon, they haven’t accomplished it. But the book does provide a compilation of classic poetry with an effective chronological arrangement. The authors have achieved their main goal in that the literary analyses and meanings of the poetry included do not devalue nor detract from the poems. How Poems Work is an excellent compilation for beginners and, as the authors suggest, a nice reminder of poetry’s evolution.

Sarah Donarski is an English teacher at Wellington College