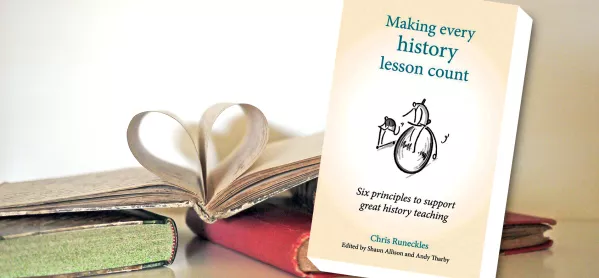

Author: Chris Runeckles

Editors: Shaun Allison and Andy Tharby

Publisher: Crown House Publishing

Details: 160pp, £12.99, paperback

ISBN: 978-1785833366

If I were a newly qualified teacher starting at Durrington High School, where the author Chris Runeckles is based and where the basic framework for this book has been outlined and developed by Shaun Allison and Andy Tharby, I would absolutely delighted.

Making Every History Lesson Count provides clear rules on the approach to teaching and learning employed by the school. It offers expectations around lesson planning and assessment, and the types of research on the mind, and the particular types of blogs from other educators, I would be expected to read. The book embodies the perfect “cookbook” or cultural acclimatisation tool. It is “on-boarding” par excellence.

Outside of this particular context, there are questions about whether it truly has, as some of the endorsements on the back cover indicate, wider relevance and traction for teachers trying to create their own successful recipe for teaching and learning in their own context.

The book aims to provide six research-informed principles to support great history teaching, yet the uncritical and simplistic acceptance of cognitive science research and its application to education undermines its purpose.

Cognitive load theory is accepted without a searching appraisal of the methodologies involved and many of the references to cognitive science papers are decades old or regurgitations from bloggers who may or may not have grasped the nuances of the research papers in the first instance. The citation of “old” papers is not really an issue in itself if it is supplemented by more recent literature showing the latest debates, developments and refinements. The absence of such work, either wilfully or through carelessness, undermines the central rationale of the book to include “lessons from cognitive science about learning and memory”. This is not possible if there is no command of the literature.

Proponents of “knowledge-rich” education have suggested that education needs to move beyond genericism, a one-size-fits-all approach to education. Runeckles is careful in the book to argue that this is not his intended aim, but it ends up becoming a generic teaching text because it is surprisingly devoid of history.

Historical examples are used to illustrate a teaching point, but they are deployed to serve the greater master of the overarching teaching model, rather than starting with the subject matter and working through how those principles could be applied. If Runeckles did this, it would be a very different book, but one, I suspect, that would not fit within the theoretical model of teaching and learning at Durrington. That the section “Know Thy Historical Period” is placed at number five, after “Prioritise Learning over Performance”, “Space It Out and Keep Coming Back”, “Set Single Challenging Objectives” and “Getting Them Thinking Hard” in the first major chapter of the text indicates that the theoretical model comes first, not the subject.

I can see this book being very useful for NQTs who need to fit in with the latest thinking about education and assessment in schools. I would also recommend, however, that their time would be enhanced by reading the cognitive science papers and popular books produced by the researchers themselves, and to read Teaching History, the journal for history teachers from the Historical Association.

Whilst they are not perfect on their own, they represent distinct, and palatable, elements of a balanced educational meal and cover in greater depth and detail the specialist areas they seek to serve.

Nick Dennis is director of studies at St Francis’ College, Hertfordshire. He tweets @nickdennis