Changing habits

When Catherine Battell was a student at St Anthony’s Girls’ Catholic Academy, there were eight or nine nuns on the staff. The Sunderland school had been set up by the Sisters of Mercy, and many of the girls’ parents remembered a time when the entire teaching staff wore habits. Of course, things had changed since then. But, still, no one could imagine a time when one would not see wimples in the corridor. A time when nuns would mix casually with lay staff and students. A time when the headteacher would not be a nun.

And then that time came. Battell (Sister Catherine) is now the only nun on the staff at St Anthony’s.

“In my mum’s generation, nearly all the teachers were nuns,” the 34-year- old says. “Now, it’s a lot more unusual. Never a lesson goes by when I don’t get a nun question. They ask if you’re allowed a boyfriend, if you’re allowed a mobile phone. All the things they can’t imagine living without.

“A lot of the girls here have a very stereotypical understanding of nuns. It’s something that’s hugely intriguing to them, because they see it as radically different from anything they would experience. The vows we take - poverty, chastity, piety - go so much against the values of the world the girls come from.”

The nun teacher was once a common figure in education, inspiring fear and guilt in Catholic schools across the country. So, too, the monk teacher: it was once unexceptional to see a teacher with a tonsure. Today, however, monks and nuns are so rare that people tend to spot them - “Ooh, look, it’s a nun!” - on the street, rather than simply passing them. Back when entire schools were staffed solely by consecrated teachers, merely turning up for registration in the morning would have constituted a 100-point jackpot in nun-spotting.

Blending in

In part, this is simply an issue of image overhaul. There are still nuns working in schools, but - particularly in Catholic schools - it can be hard to distinguish the teacher who lives in a convent from the teacher who simply chooses to accessorise her outfit with a rather large cross.

“I don’t wear a habit,” says Battell. “Nowadays, it’s a choice. A lot of the younger sisters choose not to wear a habit. So a lot of the girls here ask why I don’t dress like a nun.”

“In the past there was a very, very clear differentiation, particularly for religious women - they were in great big habits,” Cathy Jones (Sister Cathy), religious life promoter for the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales, says. “Now sisters will very often wear lay clothes, or very simple signs of their consecration. When I was teaching, I was wearing a very simple habit and cross, and some of the students couldn’t make that connection. They were expecting something from Sister Act.”

The decline of teachers in habits is also, inevitably, about decline in religious interest. In 1982 there were 217 new entrants, of both sexes, to Catholic religious orders in England. By 1992 this number had fallen to 77, and 10 years after that there were only 34 novitiates. In 2011, the most recent year for which figures are available, there were 36 new initiates into holy orders: 17 women and 19 men.

But it would be wrong to say that there is no longer any interest at all in the cloistered life. “I knew that I had to give it a go, for my own inner peace,” says Jones of her decision to become a religious sister. “I thought, `If it’s not what I’m meant to do, I can get on with the rest of my life. But if it is, then I’d have found what I’m meant to do.’”

Jones was until recently an RE teacher at St Francis Xavier Sixth Form College in South London. Like many other relatively young entrants to holy orders, the 39-year-old speaks of her decision in language more frequently heard at the start of a new romantic relationship. There was a pull towards something. A sense of possibility, of excitement. There was also fear: what if it all went horribly wrong? But, ultimately, it felt easier to live with possible heartbreak than with the unrealised potential of never having tried.

“I was scared,” Jones says. “But there was a sense that this was something I was being invited into. That this was something amazing. I wanted to see if I could do it.”

Battell uses similar language. “It’s something I gradually felt called to,” she says. “I thought I’d just do it and get it out of my system.”

Despite her own Catholic schooling, Battell did not even consider becoming a nun until she was in her mid twenties. She had taken a degree in criminology at university and had a career working in community safety. But, increasingly, she found herself thinking about joining a convent. Six years ago, she gravitated towards Sisters of Mercy, the convent that had run her old school; she took her final vows two years ago.

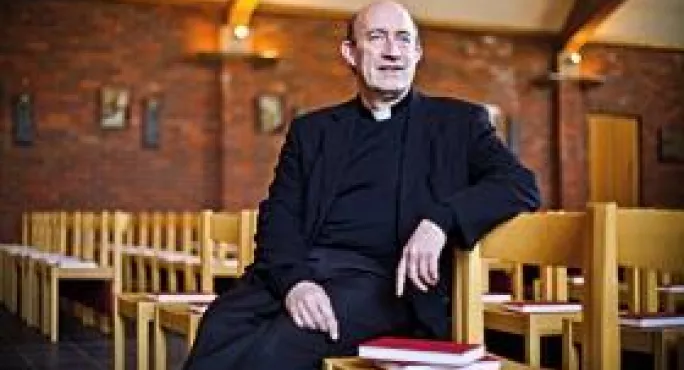

Monks and nuns, like teachers, are often career-changers. It is not uncommon for members of holy orders to have had previous careers that are not entirely in keeping with their later vows. “I worked in advertising,” says Father George Bowen, chaplain at the London Oratory School. “I was at Saatchi and Saatchi for 10 years, and then making television programmes for a short time after that.”

Business occasionally took him to Rome, where two of his friends were studying for the priesthood. On each visit, his friends would tell him that he ought to join them in their studies. “I remember thinking, `No way,’” Bowen says. “But it stuck in my head. A few years later, I awoke to the idea that it might be for me.

“I was about 30: I was getting on, really. I suppose instinctively I was settled into the idea that I was going into a celibate life. And I was comfortable with the idea that I would live in a different way, by giving my time to the community. The things that I thought would matter to me mattered less than I thought. And that freed me. It enabled me to see myself in this role.”

Working where they’re needed most

Becoming a monk or a nun, of course, is not the same as becoming a monk or nun teacher. But religious orders’ involvement in education has a well- established history, stretching as far back as the 4th century AD. Early monks were often the only literate members of society, and many set up schools within their monasteries. Gradually, certain monastic orders - the Benedictines and the Jesuits - became particularly associated with education. A novitiate would choose to join the Benedictines, for example, because of an interest in teaching.

It was not until the 19th century, however, that religious women began to play a much more active role in education. They would visit the slums and tenements of inner cities, setting up “ragged schools” for the poorest children. As Catholic labourers emigrated from Ireland to England to help fuel the industrial revolution, religious schools provided vital day care, with the added bonus that children would be fed, and often taught a trade.

Much remained the same until the 1960s. Unlikely though it seems, the era of flower power and free love had a significant effect on cloistered women, too. “From the 1960s, many of the women’s orders felt called and liberated to go out and serve those in even more needy situations,” Jones says. “Many felt they weren’t called to work in schools, which were more affluent, and went out to work with those on the margins. There was a lot of zeal to be going out as missionaries, in Africa or wherever else.”

With the advent of the welfare system and the demolition of inner-city slums, the need of even the poorest British schoolchildren was less than that of other, more marginalised members of society. “Now, many religious in this country are working with asylum seekers, refugees, women who have been trafficked,” says Jones. Many of the religious orders also have contacts in convents and monasteries overseas. So, if a Congolese asylum seeker is being sent back home, for example, monks and nuns can provide Congolese contacts to ensure ongoing support.

“Our community (Sisters of Mercy) was founded to pursue justice for women and children,” says Battell. “Before, we would have just gone into the local hospital or the local school. Now, a lot of us feel that we’re not needed so much in education but in other ministries concerned with women’s justice. We can go into prison chaplaincy, care of women who have been abused, a whole range of ministries. Before, we were much more localised. Now, we’re globalised.”

Battell, however, does work in a school: she is an RE and sociology teacher at St Anthony’s. She had not trained as a teacher before joining the Sisters of Mercy. Instead, she was asked by the superior of her community (“Mother Superior” has apparently fallen out of favour since The Sound of Music) to sustain the order’s active teaching connection with St Anthony’s.

“There’s a vow of obedience that we take,” she says. “We take that as what we are being asked to do by God. The school is very important in the community. We felt the sisters should have a presence there, especially since we’ve handed over to a lay headteacher. But it’s not where I have to stay for ever, if I feel there’s a greater need elsewhere.”

As the only nun in the staffroom, Battell is an object of constant curiosity for her students. “They’re really good at getting nun questions in, no matter how tenuous the link might be.” The questions range from the endearingly offbeat - “They always say things like, `Is Sister Act your favourite film?’ as though all we do is watch films about nuns” - to the thoughtfully theological. Battell has been asked whether she is married to Jesus, and how Jesus can have so many wives.

Monks get a similar reaction. “You wear a grey habit, and most of us have a beard and short hair,” says Father Emmanuel Mansford, a 39-year-old Franciscan monk who regularly goes into schools to talk to students about monastic life. “So when I first walk in they start laughing. I just laugh with them, maybe give them a high five or something.”

Students are often shocked to discover that Mansford had a girlfriend before joining the order. “They’re in school, so it’s difficult to ask questions about sex,” he says. “But when I mention that I had a girlfriend, they’ll ask what she did, how she responded.”

Chastity, however, is usually the least of students’ concerns. Self- imposed poverty, to the teenage mind, is a far greater hardship. “We don’t have mobile phones or TV or internet where we live,” says Mansford. “And that to them is more shocking.”

One boy, on hearing about Mansford’s circumstances, involuntarily burst out: “You have no life!” “So I said, `Is there more to life than these technical things? Can you be happy without them? If not, why not?’”

There is also a lot of confusion about the vow of poverty. “They think I sleep on the floor and we have no possessions and it’s really cold,” Battell says. Younger students often ask whether she is allowed to see her parents and whether she was permitted to take a teddy bear with her into the convent. (She was; she did not, however.)

Jones found that her students struggled to understand why anyone would willingly undertake a vow of obedience. “I could be sent anywhere: India, Rwanda,” she says. “That was important, because autonomy is so important to them. They could get their heads around not getting married as a way to serve God. But your wages not going to you - they say, `It’s an outrage! It’s not fair!’ And I say, `No. I freely choose it.’ It’s almost too much for them to understand.”

An alien outlook

Teaching monks and nuns typically hand their wages over to their monastery or convent. The money is then used towards supporting the community, and any excess distributed to sisters or brothers in poorer countries. “I do a lot of preaching here and there, and sometimes it would be nice to stop off and have a burger, just because you fancy it,” says Mansford. “But going clubbing, all sorts of designer clothes that I was into before - it just didn’t make me happy any more. Things that I was doing before lost their attraction for me.”

Possibly as a result of the absence of iPhones and designer jeans, students often have a perception of monks and nuns as almost alien beings: something very definitely other. Jones has heard a boy divide teaching staff into the categories “men”, “women” and “nuns”. “In the past, the clothes created more of a divide, a mystique,” she says. “We had a distinct identity, neither man nor woman. Now, a lot of that has gone, and the humanity is much more apparent.”

However, there is still an expectation that she will somehow be above the petty humanity of humanity. One student, for example, attempted to argue her way out of detention by asking whether she could be redeemed. “Pulling on your heartstrings, because you’re a nun,” says Jones. “Or an older teenager who said, `You’re a nun. You’re not supposed to be sarcastic.’ Well, I am sarcastic.”

Of course, any discussion of human flaws and the Catholic Church inevitably leads in one direction. Say the words “priest” and “children” in one sentence, and most people will not imagine the moulding of young minds. In 2000, for example, an investigation was launched into allegations of abuse by the former chaplain of the London Oratory School. At the time, Tony Blair’s two eldest sons were students at the school; Nick Clegg has just announced that his son will start there this September.

Then, in 2009, the former junior school head of St Benedict’s, a West London Catholic independent school, was jailed for eight years after being convicted of abusing five boys over a period of 36 years. Two years later a report was published that looked at 21 attacks at the school.

Also in 2009, a report was published showing that rape and molestation were endemic in Catholic schools and orphanages in Ireland from the 1930s to the 1990s. This, Jones argues, has had a much bigger impact than any of the parallel scandals in England. “Ireland is Catholic through and through,” she says. “The state and the system are so intertwined. So it was just such a shock to people that those they perceived as leaders in so many ways had failed them in that leadership.”

Bowen agrees. “One reads newspapers,” he says. “It’s obviously distressing for any of us involved in caring for other people, and giving your life in this way, that the whole idea of the priesthood is affected.

“Occasionally, you do say to yourself: do people look at one differently? But, generally, people are very good. Maybe I’ve just been lucky. After all, I’m in a community where people know me. But they do look beyond the collar and see the person in this job.”

Besides, says Mansford, it is not as though many in holy orders feel that they have a choice in what they do. “It’s not a career path,” he says. “It’s a grace. There has to be grace to live this way.”

OUT OF ORDER

New entrants, of both sexes, to Catholic religious orders in England:

- 217 - 1982

- 77 - 1992

- 34 - 2002

- 36 - 2011.

Photo: Father George Bowen left advertising behind to go into the priesthood. Photo credit: Alys Tomlinson

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters