- Home

- ‘Despite success, Sats results day left us hollow’

‘Despite success, Sats results day left us hollow’

Last Tuesday, on 10 July, I dragged myself into the school office for an early appointment with my computer. My anxious Year 6 team wanted to know our Sats results as soon as humanly possible. I could have told them to wait until normal school hours, but this would have only added to their anxiety levels.

We read them and immediately were confused. The set of figures did not match the headline results published at the top of the page. We worked the figures out manually and waited for an explanation of what had gone wrong. Sure enough, later in the day the headline figures were removed without explanation and it became obvious that a mistake had been made centrally somewhere, yet again.

As we sat together looking over the results, I congratulated the team for their hard work in preparing the children so thoroughly for the tests and their all-round education of the children in their care.

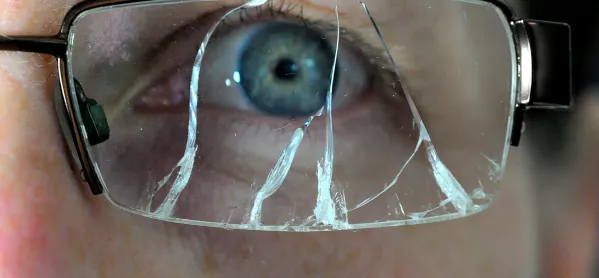

It all felt a bit hollow. The test results were pretty much exactly as we had predicted, with the exception of one young girl who did not attain expected levels because she doesn’t cope well with tests. This was a child who had felt so traumatised at the end of one of the tests that, as her paper was being collected, she had looked at the teaching assistant beside her, climbed on to her knee and sobbed.

Another child spent the year growing in confidence in her own ability but then spent the last 10 minutes in one of her tests writing “I am dumb” all over the answer boxes because she knew that she was running out of time.

Of course, I couldn’t stop to comfort her at the time, because I had to pack the test papers away in the correct packet, using the correct label, with the correct codes assigned to each child on the test register. As I did so, I was being monitored by an external adviser to make sure that we did it without cheating. Before his arrival, I had swatted up on the correct procedures for testing from the huge handbook, carried out the correct training for all staff involved and collected all of the paperwork to support the alternative arrangements for selected children. I had ensured that the papers were secure in their cardboard box, in sealed packets, inside a locked cupboard that only I had access to, with a log sheet attached to the cupboard to record anybody accessing the cupboard at any time since the arrival of the papers weeks before.

Lack of trust in the Sats system

This ridiculously mistrustful system is so bloated by its own significance that if we get any of it wrong we could face a maladministration investigation. This would see our whole team interviewed by external assessors, who would decide what we had done wrong, without informing us beforehand of what they were there to investigate or who could make career-defining judgements on those of us being investigated.

Those four days in May concluded, categorised and defined a group of children and their whole school life. Their trips, performances, cooking, storytelling, researching, problem-solving, model-making, role play, finding out about the world, rounders, football, gymnastics, computing, playing, growing were irrelevant.

They are now either at or below the "expected standard" because those tests said so.

As a school we preserved as much of what we know to be a rich school experience as possible, spending only the last few weeks before Sats practising papers. We didn't hold "Sats boosters" in any other lessons than maths and English, we kept test papers out of homework until the last few weeks and we didn't hold any after-school revision clubs or holiday sessions.

I know of plenty of other schools that feel under so much pressure to improve their results that they adopt some or all of these strategies and start preparations for the test at the start of Year 6.

My team were so anxious about the results because they knew that if the results were less than expected, we would have had to look at changing our approach. It would be perceived that our laid-back approach to Sats preparation was responsible for us doing less well than other schools.

'A stay of execution'

Our results did not feel like a celebration of a job well done, but rather a stay of execution. We know that other cohorts in the coming years will not perform at the same level, because we accept all children into our school regardless of whether or not they will meet expected levels in a Sats paper. This inclusivity leaves us vulnerable to a drop in results that will see us having to explain ourselves to Ofsted and/or the Department for Education, whose language is not that of personal growth but of floor level scores, coasting schools and sig minus ASP scores.

This deficit model of accountability, with the threat of failed Ofsted inspections, forced academisation and the sense of failure leaves us feeling that we have survived rather than thrived.

It is this constant threat attached to a drop in test scores that fuels a whole industry. My email inbox this week is already full of offers to help me plan how to improve Sat performance next year and to analyse where we are going wrong so that we can do even better in next year’s tests.

Though we try as hard as we can to hide these pressures from the children, they do have an impact. This is what the children told me:

"I found it hard to sleep for a few days before."

"I thought I would be one of the worst people and was very stressed at home."

"I felt dizzy, nervous and panicky for the first two days, scared that I would fail."

"The questions were hard and I kept thinking that I was going to run out of time."

"I felt shaky, I couldn't finish."

"Not being able to do the questions made me sad."

"When I couldn't find an answer in my brain, I was mad at myself."

When I read that Nick Gibb would “take a very dim view of any school that put pressure on children when taking these Sats because there is absolutely no reason to do so", I did not know whether to laugh or cry.

The whole bloated accountability system and resultant relentless focus upon school data is his and previous ministers' creation, making his comment akin to the historically callous and ignorant advice to ”let them eat cake.”

Siobhan Collingwood is the headteacher of Morecambe Bay Community Primary School, winner of the creative school of the year category at the 2017 Tes Schools Awards

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters