A member of the DfE’s new team being asked to improve behaviour in schools was head of an academy that subjected pupils to “unlawful” informal exclusions, Tes can reveal.

Mark Emmerson, chief executive of the City of London Academies Trust, was in charge of The City Academy in Hackney in 2016, when pupils were voluntarily “withdrawn” by parents - without these absences being recorded as fixed-term exclusions.

Revealed: The experts leading £10m behaviour programme

Related: DfE seeks 20 schools to lead on behaviour

Exclusive: ‘How our behaviour crackdown will work’

The academy said at the time that the strategy was used as an alternative for pupils whose parents did not want them sent to the “reflection room”.

Mr Emmerson has been selected by the DfE as part of a seven-strong national team to help schools curb unruly behaviour and prevent disruption in the classroom.

When first approached by Tes in 2016, Mr Emmerson said: “Our parent academy agreement has existed since 2009 when the academy opened, and was based on a model used in another school at that time.

“It is used as a targeted vehicle for a discussion with a small number of parents and students who we feel are disengaging with the behavioural expectations of the school.”

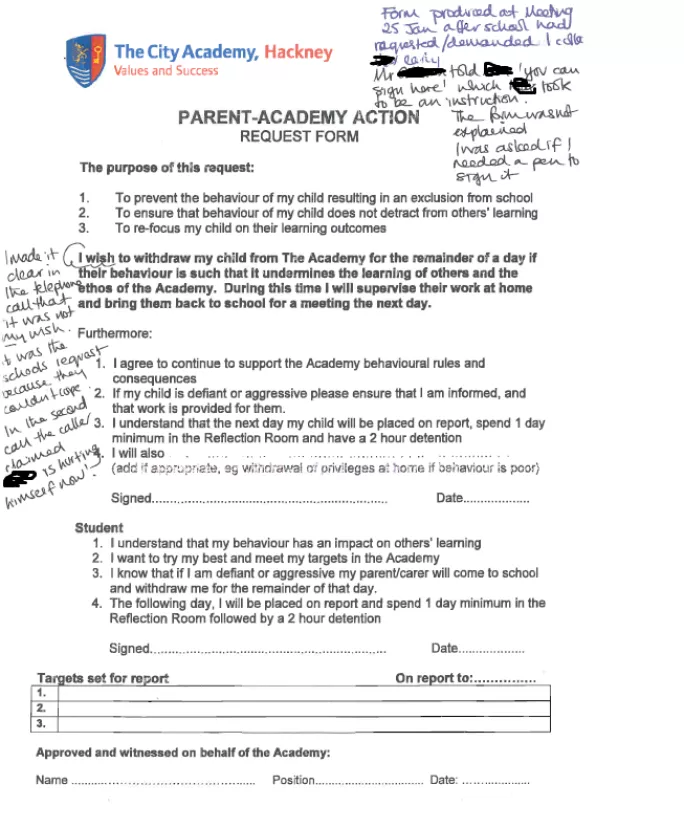

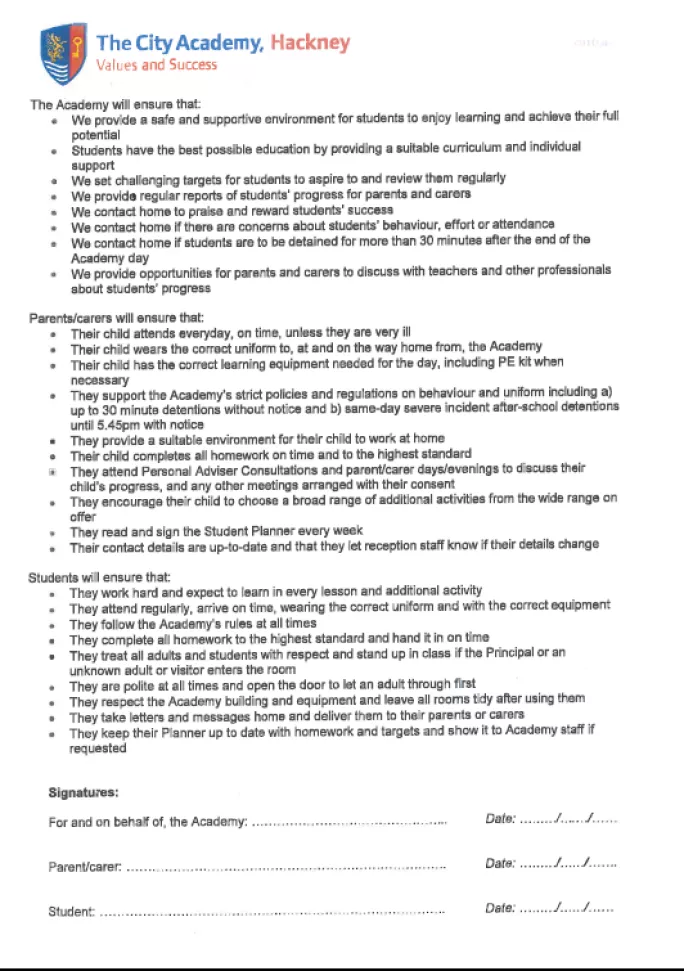

Some parents were asked to sign a form, seen by Tes, stating: “I wish to withdraw my child from the academy...if their behaviour is such that it undermines the learning of others.

“During this time I will supervise their work at home and bring them back to school for a meeting the next day.”

But after questions were raised by Tes the academy scrapped the policy and said it would record all the withdrawals in 2015-16 as fixed-term exclusions.

Mr Emmerson said: “I was happy to withdraw the request forms because our parents and the local authority need to have confidence in us, not because we had any absolute direction that it was not technically acceptable within the current guidelines.”

Sarah Hannett, barrister director at the School Exclusion Project, which provides pro bono advice to parents appealing exclusions, said at the time: ”[The withdrawn practice] is unlawful. If a child is to be removed from the school premises for disciplinary reasons, it needs to be recorded as a fixed-term exclusion.”

The distinction was important, she explained, because an informal withdrawal unlawfully “sidesteps” various procedural rights that are associated with a formal exclusion.

For example, parents must be provided with the reasons for the exclusion in writing and the governing body must be consulted if the number of fixed-term exclusions for a pupil would exceed 15 days per term. Informal exclusions tended to be used disproportionately for pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), Ms Hannett added.

Mr Emmerson said at the time that the progress of pupils with SEND and vulnerable students at his school was “significantly better than the national average, and better than the national average for all students”.

There were nine students whose parents had signed a voluntary withdrawal form in 2015-16, he added, with each form allowing a child to be taken home three times. Of these students, four had been out of school for the equivalent of one day since September 2015, three had spent half a day at home and the rest had not been taken out of school.

Also speaking in 2016, Anne Heavey, policy adviser at the ATL teaching union, said that members regularly contacted the union to discuss informal exclusions, about which it was “very concerned”.

“It can be harmful,” she said. ”[Pupils sent home] are missing out on valuable curriculum time. It’s going to affect that child’s attainment and take them away from their peer group.”

A DfE spokesperson said this morning: “He [Mr Emmerson] was chosen because of his track record in bringing about school improvement through good behaviour policies and instilling a calm ethos in schools.”

The City of London Academies Trust has been approached for comment.