- Home

- ‘Don’t play into government’s hands by blaming principals’

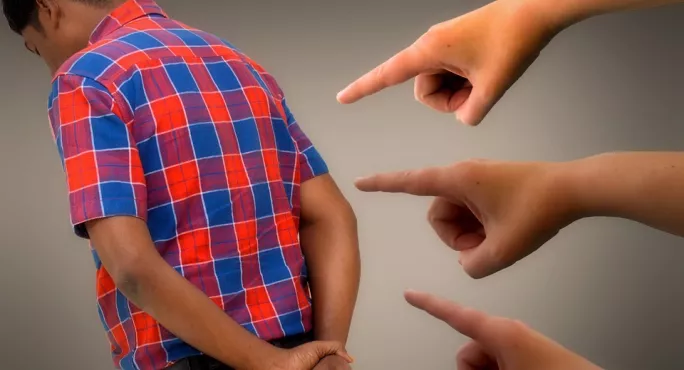

‘Don’t play into government’s hands by blaming principals’

David Hughes, chief executive of the Association of Colleges, is quite right that college principals who fail deserve compassion and dignity. There are other reasons why the current trend for pinning the blame for a college’s struggles on a single individual is a bad idea.

Firstly, it is toxic for talent management. As a wise and experienced deputy principal said to me recently: “Why would I want to step into that firing line?” Secondly, it’s the perfect ammunition for those in government who would rather spend money elsewhere.

In her recent, rushed speech to AoC conference, FE minister Anne Milton said colleges “need to use their money and resources wisely before making the case for more funding to the Treasury”. There are too many colleges in ”severe financial constraints that could have been avoided with good leadership”.

In better times for FE, it was common for ministers to come to AoC conference and say that colleges must improve standards if they are to receive new funding; Charles Clarke’s speech in 2002 was a classic of the genre. But Milton’s message is different. Leadership, she is saying, must improve before a case for extra funding is made.

No choice

If an education minister is not optimistic about Treasury largesse, this kind of message is perhaps inevitable. It’s not possible for her to blame the government (because they are “her people”), so she has no choice but to kick the ball back into the institutions’ half.

There are those in the sector that appear to agree with Milton’s proposition: in order to receive more money, we should make an example of leaders whose institutions have struggled. This is, at best, naive. Promising funding on condition of improved leadership, while spotlighting a minority of poor leaders in order to suggest this is the norm is one of the oldest tricks in the political playbook, whether we’re talking about Roman tribute or NHS funding in the early 1990s.

We’re going to see more of this from ministers in the run up to the Comprehensive Spending Review. It’s not confined to colleges - witness Lord Agnew’s recent crass bet of a bottle of champagne to headteachers that he could find savings in their schools.

Blaming an individual

FE should be wary of playing into such hands by blaming individuals for a bigger problem and we should recognise that the story, by virtue of the operating context, is very one-sided. principals’ employment contracts mean that those who might otherwise defend themselves in the public domain cannot typically do so.

FE commission transparency doesn’t extend to college board deliberations about who needs to go in order for an institution to be bailed out, and why. While it is simpler for us to blame an individual, and certainly more appealing to our sense of schadenfreude, it’s wiser to embrace the complexity of what is really going on. I know strong, expert leaders who decided to leave their colleges in recent years because it was the most effective way to secure support for the institution they loved. Sometimes departure is a sign of strength, not weakness.

It’s certainly the case that the quality of leadership and governance in colleges is variable. It’s also true that the pay gap between senior leaders and teachers is far too big, but I would argue that this is more a reflection of lecturers’ low pay - demonstrated most recently in Ofsted’s staff survey - than executive pay. If you want eye-watering salaries, check out universities.

As for “serial offenders”, there are also surely more effective methods of ensuring leaders with a poor track record are not employed by successive colleges than the fostering of a blame culture? This seems like a heavy sledgehammer employed to crack that nut.

Insufficient funding

Let us be clear, colleges’ big problem is this: for the past decade they have been insufficiently funded to do the job required of them and those requirements change far too often. Forced mergers, a halving of adult learners, low pay, mass interventions - these are not the fault of individuals.

In philosophical logic there is a flaw called affirming the consequent. All London buses are red, we might say. This object is red, therefore it is a London bus. Bad college management leads to financial problems. This is a financial problem. Therefore, it is bad management. Can you spot the mistake?

There’s a thought experiment we can use to test whether Milton’s proposition is correct, suggested to me by a recent tweet from FE policy analyst Mick Fletcher. Imagine that tomorrow you woke up and every principal and governing body in FE was suddenly extremely wise and acted accordingly. Would colleges receive more funding in the Comprehensive Spending Review as a result? I think not.

Ben Verinder is managing director of education consultancy Chalkstream

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters