Headteachers in England and Wales use data far more frequently to set targets for pupils than school leaders in other Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, new analysis has revealed.

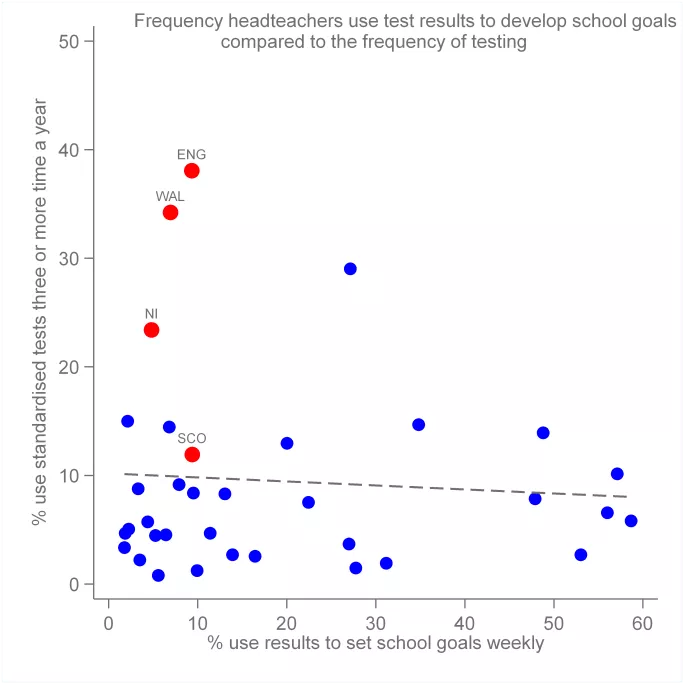

As part of the most recent Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) questionnaire in 2015, headteachers were asked how frequently they used standardised tests to set goals for their schools, and how many times a year they tested pupils.

Related: England’s pupils among the most segregated by ability

Pisa: London students do less well in Pisa rankings than GCSE

Quick read: Which pupils are the world’s biggest ‘bullshitters’?

There was little evidence to indicate that England’s secondary students are tested more than their peers in other OECD countries.

Approximately 10 per cent of headteachers reported that Year 11 was assessed using standardised tests three times or more per year. This mirrors the OECD average and is well below many other countries’ rates of testing.

However, the data did reveal that headteachers in England and Wales use data to set targets far more frequently than heads in other OECD nations.

When headteachers were asked if they used data from standardised tests to set goals at least once a week, nearly 40 per cent of heads in England said they did, with Welsh school leaders close behind in second place. The OECD average was less than 10 per cent.

John Jerrim, professor of education and social statistics at UCL Institute of Education, who analysed the data, said that England and Wales were “clear outliers along the vertical axis in the chart”.

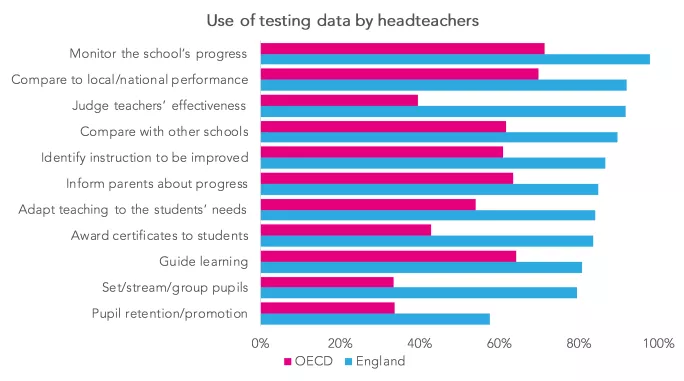

In a separate question, headteachers were asked how they use data from exams and other standardised tests. Professor Jerrim found that England was above the OECD average for using data in all areas, and English heads were far more likely to use data to judge teachers’ effectiveness or assess how teaching could be improved.

Nearly nine in 10 schools in England - 87 per cent - used data to identify how teaching could be improved, compared with an OECD average of 61 per cent.

And 84 per cent use data to adapt teaching to pupils’ needs, compared with an OECD average of 54 per cent, while 81 per cent use it to guide pupils’ learning - compared with an OECD average of 64 per cent.

English heads are also most likely to use data to judge school performance. More than 90 per cent of English school leaders use data to judge the effectiveness of their school against other schools and local or national benchmarks.

Furthermore, they were much more likely to use data to inform parents about pupils’ progress, and to stream or set pupils based on ability. Tes recently reported that England has some of the highest rates of ability grouping among OECD countries.

Commenting on his findings in a blog post on the subject, Professor Jerrim said: “Schools in England make extensive use of education data - much more so than other education systems across the world.”

“It plays a key role in many important decisions, particularly with respect to how instruction could be improved and the setting of key educational goals. At the same time, the amount of testing conducted does not seem to be excessive, at least compared to some other education systems across the world.”

“Education in England therefore seems to be very data informed. This is likely due to the ease and accessibility of the information that they are provided with. Other countries may therefore look to the experience of England if they want to encourage schools to make more data-informed decisions.”