- Home

- GCSE resits: Why I get students marking their own work

GCSE resits: Why I get students marking their own work

It was an unremarkable afternoon and I was an eager A-level English student, sitting in an over-warm classroom in West London 117 years ago. I was taught by one of those teachers who stays with you. And he said one of those things that stays with you. His name was John Rourke and he told us wide-eyed sixth-formers that education came from two Latin words meaning “to lead out”. In my mind, an image was conjured of poor and hungry people, dressed in rags and needy, lost in darkness and being led out of the all-encompassing gloom into the light. Ahead of them strode a solitary figure with a flaming torch held aloft to lead the way, a sort of Statue of Liberty-style Mr Chips.

Having something of a Messiah complex myself, this role appealed; I would take up the flame. Sometimes nowadays, midway through my best lessons, I still imagine myself in such an exalted and mythical role. However, when I turn around expecting to see the grateful masses smiling behind me, instead I can usually just about make out glazed and dull eyes staring back deep in the shadows, apparently about to either retreat or devour me. Over the decades since my introduction to the etymology of “educate”, I have felt myself pulled between the educational poles of human betterment and examination success rates. The pedagogies of Hector and Irwin compete for dominance of my professional mind.

GCSE resits: Two-thirds still do not pass by 19

More on this: ’We need a better plan for English and maths’

Background: GCSEs in English and maths ‘more useful’ than 5 passes

Sitting in the dark

One Friday just before lockdown, I had a lesson with a GCSE English resit class. It was a purely exam-success-rates kind of affair. Boot camp stuff. Do this. Remember that. Use this acronym. Write three paragraphs. The usual. Glazed and dull eyes abounded. I have a theory that when it comes to exams, many of my GCSE resit students feel themselves to be sitting in the dark, being asked to aim at targets they simply cannot see. So part of my process is to get them thinking like examiners.

At school, many of them just didn’t know anything about exam boards or assessment objectives. They knew nothing about exam technique or markers. They just did what they were told. So they rocked up on exam day, went into the sports hall in an orderly fashion, wrote a few paragraphs and walked away, hoping for the best. I don’t want my students to hope anymore. I want them to know. And so I try to get them to think like examiners. I want my students to think about every stroke of their pens, question everything they have written, read it with objective eyes, realise what they have missed and think all the time of what mark they would give to their own answer. When they leave the hall, they should know how they’ve done.

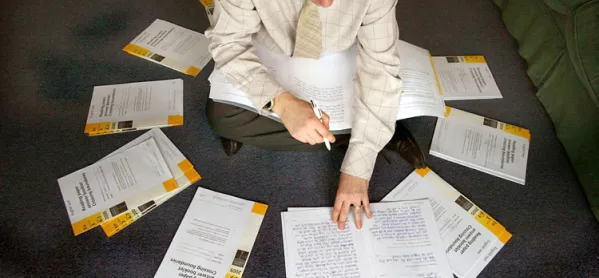

So anyway, there we were, sitting together on a Friday afternoon, all of us dreaming of the weekend ahead. In my mind, the flaming torch was definitely guttering. I asked my students to read an examiner’s report. What does that say you need to do? They dutifully made notes in their books. Then I got them to look at the mark scheme. What is the difference between levels? They tried to work out the levels. How can you get to the next level in your answer? They gave themselves targets. After all, these are no longer children, content to do as they are told, needing to be fed.

Now they are adults, and they need to know why and they need to do things for themselves. With a lot of help and a fair few dictionaries, my class managed to decode the dense passages of examspeak. They started to see what was needed and what the board wanted. Once they had read the examiner’s report and the mark scheme, then it was time to try to answer the question themselves. My students all modelled their own responses on the mark schemes. It was slow work, but it was work nonetheless. And sometimes, on a Friday afternoon, that is enough to count as success. As I circulated around the room, every single response I read was worthy of at least a grade 5. And this from students who had previously never even got close to a grade 4.

After a while, as sometimes happens, a single voice could be heard warbling up from the back of the class, intended only for a neighbour but nevertheless audible to all: “You know what? He’s getting us to mark our own work.” There was a slight edge of annoyance, as if I had been rumbled. And then there was a pause. “Although, to be fair, at least I know what I’m doing now.” The flaming torch in my imagination flared back into life. “Exactly,” I said, puzzling the Friday afternoon stupor with my sudden exultation. “That’s exactly what I’m doing.”

And I told them a story about a teacher in a classroom telling his students about the true meaning of education. They looked at me blankly and then they left, books in a messy pile at the side. But they did bloody well on that question. Every single one of them. And it was still light when I left college that Friday night.

David Murray teaches English at a sixth form college in England

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters