- Home

- ‘GCSE results will expose the UK education system’s uphill struggle to reach a world class standard’

‘GCSE results will expose the UK education system’s uphill struggle to reach a world class standard’

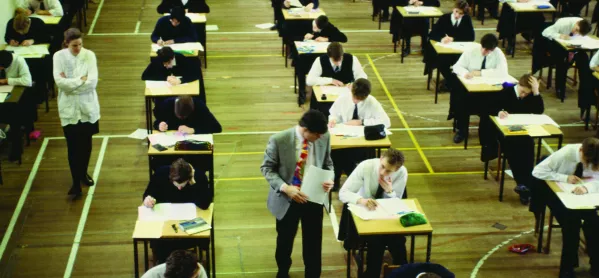

As thousands of young people open their GCSE results tomorrow, breakfast television through to the evening bulletins will cover stories of whether students have received the grades they need to go on to do their preferred A-levels, a vocational course or an apprenticeship. It is a comfortingly familiar story with viewers understanding nine A*s is great, but that a string of Es and Fs probably means retakes at your local FE college.

But, from next year all that will change with a new GCSE grading system, which will bring into sharp focus the extent to which young people in England are not yet meeting a world class standard.

So what exactly is changing? Back in 2013 the coalition government, under Michael Gove’s tenure in the Department for Education, decided that GCSEs were not challenging enough. They thought the existing A*- G grading system made it too difficult for post-16 institutions and universities to distinguish between students - especially the very highest performers.

As a result, new GCSE courses were designed (and many are still being designed), along with a new grading system of 1-9 (with 9 being the highest).

A mix of numbers and letters

Both the new GCSE courses and the new grading system are being rolled out gradually over the next few years to 2019. This means that, from 2019, pupils will be given a numerical score for each of their GCSEs on the new 1-9 scale. But, to complicate matters further, because this is happening over time, it means that in 2017 and 2018, pupils will receive a mix of numbers for some subjects and letters for others.

While this seems to be wildly complicated, and it is, these reforms do serve a necessary purpose. The new points scale, combined with new accountability measures, represent an attempt to break with the past and nudge schools to focus on both the progress and achievement of all pupils. This is rather than the current situation where schools have an incentive to focus on those who, with a bit of a push, can scrape through the five A* to C measure of ‘good’.

The new system however retains some notion of a ‘minimum standard’. Similar to the role of a current grade ‘C’, a grade 5 will be considered a ‘good pass’ and will determine requirements for young people to continue to study English and maths post-16.

However, the exams regulator Ofqual have said that a grade 5 will be equivalent to the bottom third of a current grade B and the top third of a current grade C, meaning that the bar for a ‘good pass’ will be higher than it is now.

Underpinning all this are the Department for Education’s new performance measures for schools.

Attainment 8, is the total points scored by pupils across a range of eight subjects (English, mathematics, three further English Baccalaureate subjects and three additional qualifications) and is essentially a measure of pupils’ attainment in key subjects. Progress 8 measures how well a pupil has performed in those subjects in comparison to pupils who had similar attainment at the end of primary school.

Analysis carried out by my organisation, the Education Policy Institute, earlier this year found that in order to match some of the top-performing countries, pupils in England would need to score 50 points or higher across Attainment 8 subjects.

In 2015, only 38 per cent of pupils in England achieved this, meaning that almost two thirds of 16 year olds are leaving school having failed to secure results that are on par with their international peers in top-performing countries, such as Finland and Canada.

More worryingly, this figure rises to 80 per cent for disadvantaged young people. This is not a criticism of the efforts of young people or of teachers, many of whom work tirelessly in challenging and exhausting circumstances. But, we cannot pretend that this is not a problem and that it does not have implications for England’s workforce.

Lagging behind

A survey of adult skills, conducted by the OECD in 2012, found that 16 to 24 year olds in England scored much lower in literacy and numeracy tests than most of their international peers, with a large number of people with particularly poor skills. We are one of only a handful of countries where young people have worse basic skills than older generations.

Left untreated, this will have severe consequences for UK productivity and wages, which fell during the financial crisis and stagnated thereafter.

As older people leave the workforce, the younger cohorts appear less likely to have the basic skills required to meet the challenges of the labour market. This will be even more acute for workers from disadvantaged backgrounds, only 20 per cent of whom currently leave school having reached level of attainment that is on par with other developed nations.

If Theresa May is as committed to social mobility as she stated on her first day as prime minister, she and her new team need to understand and worry about this startling gap between the middle and upper classes compared with the poorest in our society.

Making sweeping changes to GCSEs and post-16 qualifications won’t be a panacea unless it is consistent with, and supported by other efforts to, improve teaching and learning from early years to adulthood. Neither will more grammar schools.

By age 16, the gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers is equivalent to just over 19 months, but 40 per cent of that gap is already apparent when children are age 5, so greater focus must be given to the early years and primary stages.

It’s too early to tell whether the reforms to GCSEs will drive up standards and attainment or whether they will prove to be an expensive distraction for teachers who are already in increasingly short-supply and work some of the longest hours in the developed world.

Either way, when results day comes tomorrow, we should pay tribute to the hard work of pupils and teachers. But we should also reward them with an education system that gives them a chance of reaching a world class standard.

Natalie Perera, is executive director of the Education Policy Institute

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters