How to meet the needs of child prodigies?

To many, the idea of a childhood genius - a prodigy, if you will - has an almost mythical quality. The tales we read in newspapers each year of young children taking GCSEs and A levels portray them as superhuman.

But isn’t it an impossible paradox? Surely, having a towering intellect can’t be teamed with playing with dolls or soldiers? But it is.

These children look like any other children. They don’t go around wearing bow ties or carrying large piles of books. They are not all pupils at private or even grammar schools.

Instead, most live normal lives, having fun, taking part in games; but all the time they are having to combine this with possessing an exceptional intellect, which means they often celebrate achievements most children attain years later.

TES has met some of these young people trying to negotiate the tricky path between making the most of their academic gifts and having the freedom to act their age. They and their families have told us their stories and explained the unique and difficult decisions they have had to make about their education and future.

Wajih Ahmed

Wajih is the University of Southampton’s youngest ever student, having started his economics degree at 14.

Wajih’s potential was spotted early and encouraged by his parents, Saadia and Usman. Some of his achievements are nothing short of jawdropping. At the age of 3, Wajih could understand simple mathematical concepts and by the age of 8 he was working at GCSE level at home, while at his primary school he followed the normal curriculum.

Wajih took his maths GCSE aged 9, and got A*. By 12, he had taken his maths and further maths A levels, and had been awarded A* grades. He had also taken an additional four GCSEs, in the three sciences and statistics, getting the top grade in each one.

By 14, Wajih had taken 10 more GCSEs, an AS level in economics and A levels in physics and chemistry.

He still lives at home in Hampshire with his parents and his brother Zohaib, aged 13, who is also gifted - he achieved A* grades in maths and further maths A levels at the age of 10. Saadia, who trained as a lawyer, is a full-time mother and Usman works for the Ministry of Defence.

“We thought 14 was a good age for Wajih to complete all his GCSEs and A levels,” Saadia says. “I think it’s very good that he has experienced working with people from another age group already - most children don’t have that opportunity. He is able to make friends with people of all ages.”

In Year 9, he studied for his GCSEs along with Year 11 pupils at Thornden School, his local comprehensive, and had his own timetable so that he could also attend Barton Peveril Sixth Form College in Eastleigh.

“When he wants something he works really hard. All we have ever told our boys is to give their best effort,” Saadia says.

But Wajih’s proud parents say their son is enjoying himself and having fun. They insist that when he was working to achieve a university place he “spent a few hours each day doing focused work”.

“The rest of the time he spent playing. He wasn’t sitting in his room all day working, he has friends and a social life. The assumption that gifted children are `nerdy’ is wrong,” Saadia asserts.

And Wajih, now 15, is settling well into university life. “I’m really enjoying it and I’ve made a lot of friends, but I also still see my friends from school,” he says.

“The other students don’t treat me that differently. When they ask about me I just say I’m 15, I don’t say a lot else about my exam results. The work is great. It is a lot more challenging. I really enjoy the independence of university.”

Wajih hopes to become an actuary in a City firm when he has finished his studies, but first he wants to get a PhD in economics at a London university. “He’s had a head start in life and he is loving it,” his mum says, proudly.

Niall Thompson

Niall had achieved A* grades in A-level maths, further maths, statistics and physics, and started a maths degree at the University of Cambridge by the age of 15.

Niall, now 19, was brought up by his mum Bev in Manchester, and they lived with his grandparents for much of his early childhood. Although he had always been thought of as “bright” by his teachers, it wasn’t until he started secondary school that Niall’s mathematical talent was spotted - in a cognitive ability test and his behaviour in class.

“The teacher noticed I took no time at all completing my work in the mixed-ability class,” Niall says. “We were encouraged to ask for more work when we had finished, and I kept asking, and she kept giving me more. In the end I was obviously so annoying she gave me a GCSE textbook and asked me to try that. I think she thought there was no chance I could do it, but I ended up giving it back to her having completed the exercises.”

From the beginning of this extraordinary academic experience, Niall took control of his own education. He, supported by his family, doggedly pursued his ambition to study at university as soon as possible.

At the end of Year 8, Niall had taken his maths and further maths GCSEs. In Year 9, he was going to sixth form part-time to do AS-level maths, wearing his school uniform and “sticking out like a sore thumb”. He also set himself a target that year of taking English and science GCSEs at school, plus AS levels in two other subjects.

This decision was partly dictated by the fact that he wanted to start university as soon as possible and Oxbridge academics frown on applicants who have had a break from studying maths. Niall went to sixth-form college full-time from the beginning of his Year 10 so that he could get his A levels.

“All I wanted was to be given the level of teaching that I required, and my high school couldn’t give me that. I knew I wanted to go to university, so I knew I wanted to take other A levels. It felt pointless to put my maths studies on hold. I had a real love for it and wanted to carry on.”

His school was against the plan, but Niall’s mind was made up. “My family gave me determination and drive, as well as tenacity,” he says. “I wouldn’t take no for an answer and that drove me forward. When I was 14, I felt like I was 17, as I was treated the same as others that age.”

Tutors assessed Niall’s maturity before he was given his place at Magdalene College, Cambridge. They also spoke at length with his mum about whether he was ready to move hundreds of miles from home and live independently at such a young age.

Niall admits that choosing to accelerate his education put him under pressure. His workload didn’t ease up when he started at Cambridge in October 2009 - he was working at least 50 hours a week, hardly most people’s impression of student life.

But, aside from the fact that he was studying an intellectually rigorous course, there was another reason. Being 15, his welfare was closely monitored by a personal tutor, who would often receive emails saying he had been seen “near” the student bar, reminding him he was not allowed to go in. Niall says that he felt “watched” and socially isolated.

Despite this, Niall, who achieved a 2:1, doesn’t regret any decisions about his education. At 19, he is a thoughtful, articulate teenager who already has a degree, and he is studying for a master’s at the University of Manchester - a place with a “completely different feel”. He plans to undertake a PhD and then work in industry or for the government.

“My advice to anyone else planning to do what I did is never forget why you are studying in that way in the first place. It’s easy to let it get to you, but you have to remember the reason is because you love the subject, and nothing should distract from that.”

Mia Speranza

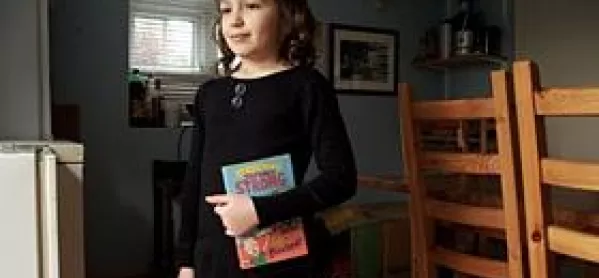

Mia spoke coherently at 12 months, could read at 2 and could write by 3. Now 7, she enjoys reading novels popular with teenagers. Teachers have assessed her as working at the level of a 12- or 13-year-old.

Aged 3, Mia was assessed by an educational psychologist and had an IQ of 132. When she was tested again a year later, her IQ was 149. To put this in context, an average adult can expect to score 100.

Mia’s parents Michael and Nicola have struggled to find the right way to educate Mia. At the age of 7, she has already been to three schools, in the state and private sectors.

“Having a child like this is wonderful and terrifying in equal measure. You desperately want to do the right thing, but there’s very little help to show you what the right thing is,” Michael says. “Our experience of the education system, at least until the present school, has been hostile rather than helpful. It’s been a bit of a shock.”

Mia does well at many tasks she starts, for example, piano playing, but has a limited attention span. Being given a task below her ability bores her, and means she may start acting up, refusing to work and getting in trouble at school. Michael and Nicola are worried by this. They are anxious not to “hothouse” their daughter. They are not pressing for Mia to take exams early, just “to be able to do whatever interests her, and to be able to go as far with that as she wants to go”.

They have found some reluctance from teachers - not in her current school - to cater for Mia’s needs. In one school, Michael and Nicola were told that teachers didn’t believe the educational psychologist’s assessment, and Mia was given work she’d done at home two years previously.

“Mia is a brilliant little girl. She’s funny, she’s sensitive and she loves to cause trouble, but she does it with a twinkle in her eye. All we want is for her to receive an education that interests her, stimulates her, catches her imagination and makes her want to learn more,” Michael says.

Mia’s parents have sought advice from Potential Plus UK, the gifted children’s charity. This has given them access to other parents in the same position. “If most other parents were saying, `My son said “mummy” for the first time today’, how do you tell them that your child is having a conversation with you about death and telling you that 3 + 5 - 4 = 4?” Michael asks.

Mia currently attends Brookham School in Hampshire. Her headteacher Diane Gardiner says that enrichment activities are working to keep her interested and happy at school at the moment, but in future she might have to work ahead of her peers. “We work really hard to make sure she is not bored, and it helps that she is not the only very bright child in her class, so she has a level of challenge from her peers,” she explains.

“Since Mia has been with us, we’ve done a lot of work helping her understand how to work with others, and she’s now much better at working as part of a group,” Gardiner says. “She really needed to do that, otherwise she would find life very tough.

“In some areas - research, problem solving and reading around a topic - Mia is working at the age of 12 or 13. Her reading is astonishing, she is good at maths, but not as good as some boys in her group. She is ahead in all areas.”

Mia, who says she dislikes sitting exams and homework, but loves art and music, has a range of careers picked out - sports teacher, dress designer, writer, pop star and chef. When asked what her dream school would be, she says she would choose to be homeschooled - so that she could go on fun educational outings with her family. “I used to be bored when I went to other schools because I was given really easy work to do, and I did it really quickly, then there was nothing to do,” she says.

“Teachers always thought you could only listen if you didn’t look out of the window, but I can do both. Now I get harder work which is more my standard.”

Cameron Thompson

Cameron’s parents had an inkling that their son might be gifted when he accused his reception class teacher of lying.

The little boy had come home from school, eager to tell his family about a new fact he had been taught: numbers start at zero. When his mother Alison happened to mention that there were also negative numbers, Cameron - amazingly for someone of such a young age - immediately understood the concept. And the next day he asked his teacher, “Why did you lie?”

Luckily, she saw the funny side, but the event had serious consequences - it started Cameron on an educational journey that led to his starting degree-level work when he was 11.

At the age of 7, a family friend set him an 11-plus maths paper, which he completed without dropping a mark. The only problem was that he didn’t know how he’d got the questions right; it was intuitive.

But it wasn’t until secondary school that things really took off. In Year 7, Cameron scored one of the top marks in the country in a cognitive ability test set by his school. His headteacher suggested that Cameron do higher-level work and by the December after starting secondary school he had completed all the GCSE maths modules. He took the exam aged 12 and his A level aged 13. In parallel to this, Cameron had started taking short courses in maths through The Open University at the age of 11.

The intention was never that he should start a degree - his parents were merely looking for a way to help their son. But Cameron will graduate from The Open University this summer aged 15 - at the same time that he will take GCSEs in his other subjects. He is thought to be one of the few people in Europe to study for a degree at the same time as being in school. His parents joke that Cameron is looking forward to putting letters after his name in his school books.

“We didn’t set out for him to do a degree, just for him to work at a level that he was happy with. Even now, I don’t think he’s totally found his level,” his father, Rod, says.

Cameron, who was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome when he was 13, says he wants to be a university academic. “School is pretty good. I get singled out a lot, and occasionally mocked by other pupils, but I don’t mind. I usually just ignore it. If I get in a verbal argument with another pupil I usually win,” he says.

The Asperger’s manifests itself in other academic ways. He says it means he is very capable at IT, the sciences and maths but “can’t stand” more subjective subjects such as art and RE. He also has a fantastic memory.

Cameron faces big decisions this year about his future. He would like to study towards a master’s degree, but his parents want him to be a “normal boy” and attend sixth form. The current plan is that he will take IT and physics A levels, and study for master’s level courses through The Open University.

His future is already full of opportunities. Cameron has had invitations from universities to come and see their computer programming and robotics work, and academics at the University of Cambridge want to speak to him when he is 17.

“People are right to say you shouldn’t accelerate children, but there is only so much of the same (work) that children like Cameron can do,” Rod says. “To assume children are the same is a flawed argument. This is a hobby for Cameron, why can’t he pursue his hobby? I have no doubt that Cameron will end up doing something like working at Nasa, with lots of other `geeky’ people.”

How to decide what is best for super-bright children Photo: Seven-year-old Mia Speranza works at the level of a 12- or 13-year-old and has an IQ that makes her eligible for Mensa. Photo credit: Julian Anderson Original headline: Young brains of Britain

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters