How the poorest school beat the odds

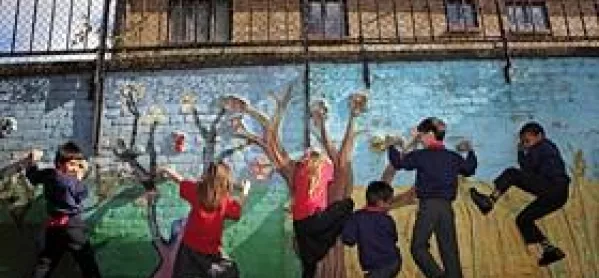

At first glance there is nothing unusual about Duncombe Primary School in North London. Children play happily in the well-maintained playgrounds, and appear to learn contentedly during stimulating lessons taught by impressive staff. Everyone goes about their business in a calm and efficient fashion. Indeed, Ofsted inspectors have rated the school as good with outstanding features. In many ways it echoes high-performing primaries around the country.

Yet dig below this tranquil surface, and ask a little about Duncombe’s history, and a very different picture emerges. Far from being a long-term beacon of quality and learning, it confronts daily a range of unrelenting problems. For this is the “poorest” mainstream school in the country.

According to the latest available official data, 95 per cent of the children who come to this school are eligible for free school meals - the highest rate for a mainstream primary or secondary school in England. It is a staggering statistic. In fact, since the beginning of September, this proportion now stands at 99.6 per cent - all but two pupils are poor enough to qualify for free school meals.

But for teachers at Duncombe the poverty experienced by their pupils is much more than a number. It influences everything they do, and has resulted in the creation of a unique and extraordinarily successful school. Far from being a “sink” school, overwhelmed by poor results and bad behaviour, it has accepted poverty as a fact of life - and triumphed.

Teachers daily go above and beyond the call of duty for the sake of children and their families, often putting in several hours of extra work a week. They not only successfully teach their pupils but also help parents solve problems with housing, immigration or domestic violence. Scratch the surface and you discover this is as much a community, with facets of social welfare, as a high-performing school.

A borough of extremes

Duncombe Primary, which has more than 460 pupils, lies in a busy part of Islington, inner-city North London, a local authority that is home to some of the capital’s richest and poorest residents. Almost all the pupils at the school live on the often desperately poor estates that surround it, sitting cheek by jowl with large and expensive homes. A high proportion of the local population are from refugee and asylum-seeking families and more than 75 per cent of children at the school speak English as an additional language.

Many of the pupils are in care, and school staff are familiar with visiting social workers who have very serious concerns about others. Some of the children are neglected, or live in homes where they regularly witness domestic violence.

The list of issues goes on. All too often children turn up to school having not had a full night’s sleep or without breakfast. Then there are a range of behavioural and learning challenges.

Many would view these as insurmountable obstacles. Many would take the view that without a more balanced social mix, good results would be more or less impossible. Yet key stage 2 test scores are reliably coming in above the local and national averages, which is testament to the hard work of everyone in the school, and Ofsted has heaped praise on the school. In short, this is a school that defies all the odds.

First and foremost, this is a story of how high-quality, consistent, knowledgeable leadership and teaching can achieve amazing things. Headteacher Barrie O’Shea has been in place for the best part of a quarter of a century, joining what was then a failing school on what was meant to be a temporary basis in 1989.

Things were so bad that at one stage, just before O’Shea arrived, the entire staff resigned. The school, rarely full because of its well- documented problems, was seen as an easy dumping ground for excluded pupils, and it was suspected that the former Inner London Education Authority saw it as a good repository for inflexible and difficult teachers.

O’Shea was the sixth head to be appointed in the year he joined and he did not expect to be asked to stick around. “The school was thought by inspectors to be beyond control and was due to close at the end of the summer term,” O’Shea says. “It was a struggle. Duncombe was a troubled school and we started our journey from a low base level.” Slowly, however, he brought change to the primary and was appointed permanent head.

Jump forward 23 years and it is a place transformed. Today the school is popular and academically successful. But the intake remains desperately poor and the challenges posed by economic and social deprivation are still omnipresent.

Ready to `respond to anything’

Staff happily take on social work unthinkable in more affluent primaries and secondaries. They help parents tackle problems with housing, immigration, police, health matters and domestic violence. According to a proud O’Shea, his teachers will “respond to anything”. Among the more obvious contrasts with what might be termed more “normal” schools is the presence of a home support worker and a community support worker employed by the school. Their professional skills and local influence bring extraordinary results. For example, parents who come to them suffering domestic violence can expect to be rehoused quickly because of the school’s close relationship with the local authority.

And there are other, even more unorthodox, duties. The school will support the families of pupils who are illegal immigrants while they attempt to “stabilise their role in the country” and apply for legal status.

Given the huge ethnic diversity of the surrounding estates, it is no surprise that three-quarters of children at the school have parents whose first language is not English. Often a parent will ask for help after their child has been attending the school for a while, as it is well known locally that they can trust staff to assist them and maintain confidentiality.

“The people we go to in order to get help for parents know we want nothing for ourselves, just for parents,” O’Shea explains.

But the school also reaches out to troubled students from beyond its own borders. Pupils excluded from secondary schools, those who have left the care system, and those at risk of becoming Neet (not in employment, education or training) are all welcomed with open arms when they come looking for help.

When this work started some years ago, the pupils were former Duncombe children who turned up at the school, returning to a place that represented security and stability in a mad world. But now teenagers from further afield appear at the school gates, having heard on the local grapevine that it is somewhere they can get help and maybe even continue their education.

“We would rather help than have these children roaming the streets,” O’Shea says matter-of-factly, as if any humane school would do the same. “Sometimes we will have one teenager with us, sometimes it is six. The longest they have stayed with us has been for three and a half years, and the shortest for one day.

“We had one lad excluded for taking a knife into his secondary who did his GCSEs with us and received good results. We found him to be good as gold and he went to college.

“We take children other schools wouldn’t dream of taking.”

An unlikely success

Despite its disadvantages, Duncombe has beaten the odds. Repeatedly research has shown that deprivation equals underperformance. And poor children who go to school with other poor children do even worse. According to a report by The Sutton Trust published three years ago, pupils eligible for free school meals in the most deprived schools on average achieve two grades less in their best eight GCSEs compared with free-school-meal pupils in the most advantaged schools, after individual factors are taken into account.

A study produced for the government this year by academics from the Institute of Education and Birkbeck, both University of London, and the University of Oxford found that differences in attainment related to background influences that emerged at age 3 remained until the child reached 14.

On paper, this Islington primary is among the least likely to succeed anywhere in the country.

According to Liz Todd, professor of educational inclusion at Newcastle University, the reasons children from poorer schools often have low attainment include lower expectations of pupils. She says that characterising children as “disadvantaged” becomes self-fulfilling.

”(If pupils need extra help) this often means that we focus on people as problems, when all people have personal resources and the means to achieve, and to solve their own problems.”

This is the stereotype that has been all but eradicated at Duncombe, where it is an article of faith for staff to have high expectations of all pupils. The focus is on improving children’s literacy and numeracy skills; it dominates every lesson.

Children who join the school’s nursery and reception classes have widely different abilities in speaking and other basic skills. Their first languages include Somali, Arabic, French, Hindi, Turkish, Bengali, Greek and Albanian. They need support as early as possible if they are to reach the expected levels in reading and writing later on in their school career. It is common for pupils to work with a speech and language therapist; others have one-to-one support.

What is most striking is how much children at the school enjoy learning: nursery teachers have been asked to set homework. “They want to be like their sisters and brothers (who are ahead of them). I’ve seen kids cry when we told them they wouldn’t have homework,” the school’s foundation stage manager, Bernadette Alexiou, says.

Sitting in on a Duncombe class is an uplifting experience when you consider what many of these pupils endure beyond the safety of the school gates. The Year 1 group I visited worked well in a formal classroom, listening attentively to their teacher. The atmosphere was lively and supportive. All the pupils were engrossed in their work. Yet this is a class where, because of a range of problems, the pupils might be expected to have trouble sitting still.

Many still have a “language deficit”. Teachers say that some are deprived of conversation at home. Their parents do not talk to them much or read them books. Consequently, school staff place great emphasis on talking in order to improve oral skills and vocabulary. They praise children when they improve and expand their vocabulary, and they are encouraged to reward clever conversation with various signs, games and sound effects. The children listen rapt when the teacher reads, and eagerly join in when they can.

One of the focuses of the school is to broaden pupils’ horizons, giving them experiences they might never have at home. Many will hardly have left Islington. Teachers are committed to taking pupils on visits so they can see the world around them in the capital and beyond.

The kind of educational results achieved by Duncombe do not come cheap. But the school has been given pound;240,600 by the government in pupil premium funding for this academic year. The initiative, which awards an extra pound;600 in funding per free-school-meal child on the roll, has not been without its detractors. One recent survey by Ofsted claimed that the project had made little or no difference. One major flaw seems to be that heads do not actively target the cash at the pupils who need it and cannot therefore display direct outcomes to justify the additional investment. Of course, in a school such as Duncombe where more or less all the children qualify for the extra funding, this is not a problem.

Here it is being used to pay for an interesting intervention - “partnership teaching”, in which up to three teachers are employed for the two classes in each year group. This allows them to work with smaller groups of children or to “team teach” pupils. Planning and preparation time is covered by the third teacher. It means children get extra attention from adults.

“We take every opportunity to reduce class sizes to manageable groups - similar to those found in the private sector - through our partnership teaching approach, and use our additional staff to carry out interventions as the necessity arises,” O’Shea says.

Relentless focus on outstanding teaching

O’Shea and his staff believe that this approach helps children to achieve, that they can’t be successful unless there is a relentless focus on outstanding teaching.

Anyone who has ever touched on the world of education can tell you that it is littered with schemes designed to raise the aspirations of poor pupils, change their attitudes to school and keep them engaged with education. Similarly, anyone who works in schools will tell you that all too often these fail or go untested.

So what works? The evidence from Duncombe suggests that “extended schools”, which run activities for the local community, think about the whole child and address the issues of family life, can certainly help to foster academic success. This is a school that is not afraid to open its doors to outsiders, an attitude that stretches beyond the many older pupils who turn up asking for help. On average, each week 60 people volunteer, thought to be one of the highest rates in the country.

Teachers also try to involve parents as much as possible in the life of the school. They are invited to meetings where they learn about the curriculum, and take part in art activities and workshops where they can see the resources teachers are using. There is a good reason for this. The experiences of more affluent schools show that pupils benefit hugely if their parents are engaged in their education. The parents at Duncombe are given every opportunity to learn what it is that their children are up to at school and why it is so important that they succeed. And succeed they do.

What could quite easily be treated as a hopeless situation is now being looked to - correctly - as a role model for other such schools, and O’Shea says he is more than willing to share his and his teachers’ experiences at the school.

But the recipe is simple: investment, high-quality teaching and leadership, and a commitment to the wider community. Teachers give children confidence and ambition, as well as the important skills they need to defy the educational odds.

What a school, and what a credit to so much that is great in our education system.

The school

461 total number of pupils on roll (all ages)

8.7% pupils with SEN statement or on School Action Plus

75% pupils with English as an additional language.

Photo credit: Nick Sinclair

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters