- Home

- Investigation: Why primaries fear their falling rolls

Investigation: Why primaries fear their falling rolls

It is the issue primary heads would rather not talk about. But it is not going to go away.

Today, a Tes investigation reveals that, by 2022, tens of thousands of primary school places will be unfilled, leading to staff redundancies, larger class sizes, and even school closures.

Yet the issue is a sensitive one, as heads fear that discussing their falling rolls will jeopardise parents’ confidence in their schools and locking them into a spiral of a decline.

Exclusive: Primaries at birth rate breaking point

Background: Population bulge prompts fall in proportion of pupils receiving first choice secondary place

News: DfE cuts projections for growth in pupil numbers

“Schools don’t want to talk about this,” says Karen Buck, Labour’s parliamentary candidate for Westminster North, an area where spare capacity in primary schools will peak at 21.5 per cent by 2022. “They think parents will see it as a sign of falling standards, even though it absolutely is not. This is a demographic issue.”

The problem stems from the fact that, following a pupil population “bulge” in the 2000s, cohorts in Reception and key stage 1 classes are now smaller than the cohort currently in key stage 2. And the gap is only going to get wider.

Timo Hannay, a statistician at education data website School Dash, analysed Department for Education data to show that within three years, there will be around 100,000 unfilled places - based on existing capacity - equating to hundreds of average-sized primary schools.

“There are two things that will drive down primary enrolment,” he said. “The new Reception classes coming through will be smaller than any previously, and the current, smaller reception cohort will work its way through the system to replace the current year 5 and 6, so they will be smaller overall.”

Meanwhile, the biggest cohorts will leave over the next few years, driving enrolment down further. Nonetheless, Mr Hannay says the problem will not affect schools in a uniform way - it is likely to hit certain types of school harder, leading to possible mergers, or even closures, as they struggle to balance their budgets in the face of reduced funding levels.

Dave Thomson, a statistician at FFT Datalab, says that local authorities will “need to deal with this when they do their place planning”.

“There is already quite a lot of spare capacity at primary and it’s set to increase with the lower birth rate,” he says. “The 2018 [birth]figures might be a temporary blip but if the 2019 birth rate is even lower, it could have a significant impact in the future.”

Mr Hannay said the impact of this is likely to be “lumpy” rather than uniform, affecting certain types of school much more severely.

Primary school places hit harder in smaller schools

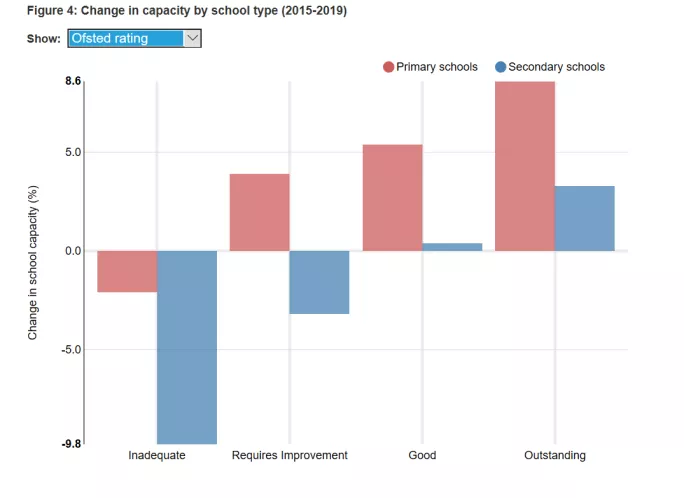

Smaller primary schools and those with lower Ofsted ratings - which were already suffering from lower pupil numbers in 2015, before current declines began - will be hardest hit, alongside schools in metropolitan areas such as London, where competition for places is fiercer, his analysis shows.

“The data tells us that primary school enrolment has been falling, and we know it has impacted some schools more than others - you would expect it to hit schools with lower Ofsted ratings the most,” he said.

“Some might see that as market forces at work. Obviously, that is controversial, but some might see this as an opportunity to close schools that are not performing or where there is not demand for them. But there are lots of knock-on effects of that.”

In the graph below, based on data from the Department for Education, primary schools rated “inadequate” by Ofsted saw their pupil numbers fall by 2.1 per cent between 2015 and 2019, whereas those rated “good” saw their pupil numbers rise by 5.4 per cent, and “outstanding” schools were boosted by an 8.6 per cent rise.

While these patterns are more drastic at secondary level, Mr Hannay said the issue of spare capacity in primary schools will become more pronounced as the population “bulge” works its way through the system.

Tiffanie Harris, primary specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders, warned that any downgrading of schools through the new Ofsted framework would have serious repercussions on their pupil numbers.

“If a school’s rating changes from outstanding to good, then a lot of parents don’t understand that and simply move their children,” she said.

“Especially if a school has been ‘outstanding’ for a long time, if it is downgraded, parents don’t see that the school is still providing a high-quality education. If you go from ‘good’ to special measures that rocks a community.”

The ‘London effect’

In London, where the competition for pupils is becoming particularly intense, the higher number of free schools exacerbate the problem of spare capacity.

Anne Lyons, a former president of the NAHT teaching union, said that in her part of north-west London, “numbers have plummeted very quickly within the space of four years”.

“A lot of school leaders are just trying to keep their heads above the parapet,” she said. “One of the biggest worries is that there is still a move to open free schools. In Harrow, there is a free school opening when schools in that area have falling rolls.

“Heads of maintained schools in that area are very concerned about their numbers, as well as the cost - most of us would have no objection to free schools at all, but they should be in areas of need,” she said.

Ms Lyons added that schools with spare capacity - and therefore less funding - are also more likely to serve disadvantaged communities.

“The schools that suffer are the ones that are traditionally less popular, and they are the schools with the most vulnerable pupils,” she said.

This is echoed by Ms Buck who points to the latest council data for Westminster schools which shows that, many of its primaries are two-thirds empty, having already lost one class.

“In our schools, there are a significant amount of them merging or reducing intakes,” she says. “One local school had to give redundancy to all its teaching assistants and then reemploy half of them.”

As pupil numbers have fallen, a free school - Minerva - opened in the area, compounding the problem.

“It was always half full, and it only lasted four years. It is pretty clear we did not need a free school - it was never going to sustain itself. When you’re going through a period of change, you don’t want the random, unplanned nature of free schools opening.”

A further issue she raised was that families struggling to cope with living costs in inner London ended up moving into temporary housing in outer boroughs, where capacity is more stretched.

Essentially, this leaves inner London schools empty, while adding to the burden of schools with full rolls in Enfield or Uxbridge - an example of some of the “lumpy” impacts of the problem.

Mr Thomson of FFT Datalab said a lot of spare capacity in the system in London would mean some schools were no longer viable and would be forced to close.

“I don’t think we appreciated how big a drop [in the birth rate] it was in 2018,” he said.

And he fears many areas will suffer. “It looks like a national rather than a regional problem - in every region there are local authorities where the birth rate has dropped considerably. This won’t just be a London issue.”

Mr Hannay’s predictions are slightly different to the DfE’s own forecast, as these currently “foresee a slower decline in which total primary school enrolment is flat for the next two years, followed by a reduction of about 100,000 pupils, mostly during 2022-2024.”

He says the fact that DfE predictions include nursery provision, where the falling birth rate is offset by increased participation rates, may account for this.

“Demography is not destiny, but it certainly offers some guidance to the future for schools,” he says. “So if you’re running a primary school, especially one that is small or has a low Ofsted rating, then brace yourself: forewarned is forearmed.”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles