- Home

- ‘Isolation units are draconian psychological torture’

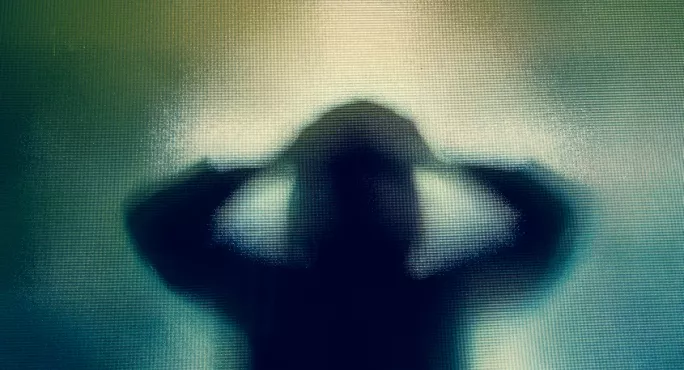

‘Isolation units are draconian psychological torture’

I am aware that the following sentence is going to cause many a hissy fit among readers, but, frankly, I don’t give a damn. Sending students to isolation rooms is a draconian, outdated form of psychological torture, which should have no place in our education system.

Now, before anyone says, “How am I supposed to teach my lesson if I can’t send a disruptive student to isolation?” I would like you to think of the teacher in 1986 saying, “How am I supposed to teach my lesson if I can’t cane the disruptive ones?”

It was 1986 when corporal punishment was banned in state schools across the United Kingdom. Now, in 2019, the days when a teacher could demand a student to bend over so that they could whip their buttocks with a wooden stick are long gone.

Why isolation units are wrong

For my generation, when we look back at corporal punishment, we are utterly horrified that it was ever legal, let alone common practice. I have no doubt that a future generation of teachers will look back at isolation units with the same horror, shock and disbelief.

Think for a moment what an isolation unit actually is. You are taking a child, forcing them to sit in a chair (often facing a wall or a boarded booth), forbidding them from speaking or making any contact with anyone around them, and then leaving them there for around six hours a day. In some cases, for up to five days.

Were I forced to sit in an isolation unit for an entire working day, I would probably end up quite fidgety, rocking back and forth on my chair. And it would almost certainly impact on both my mood and my emotional wellbeing. If you forced me to do it for a week, I would probably start losing my mind.

I challenge any teacher in support of isolation units to find a mentally healthy person who can sit in an isolation unit for a day and not feel depressed and agitated by the end of it.

Staring at a screen

Some people may argue that the isolation units in their schools aren’t like this. But, in reality, they probably are. I have seen schools attempt to prettify them by calling them things like “the reflection room”. Ironically, in one such “reflection room” there were no windows and the children had to sit in little boarded-up booths - there was literally no reflection.

I distinctly remember the austere atmosphere as I walked into one such room. A student was asleep with his head on his desk. In the next booth along sat a student watching a documentary on a computer screen with no audio or subtitles - he was literally just staring at a screen. It was depressing.

Just to be clear, if a student needs to leave the classroom because they are being a danger either to themselves or to other people, then I fully support sending them to a place where they can calm down under adult supervision in a safe environment.

However, in reality, isolation units are used as a standard part of a school’s disciplinary process. They are filled with students who failed to hand in homework, refused to remove a nose ring or just decided for whatever reason to sit in a different seat. Teachers are using isolation units casually as a form of everyday punishment for children who just wind them up the wrong way. I know these students; I know how you feel. But sending them to an isolation unit is not justifiable.

‘Until she cracks’

I remember one teacher triumphantly proclaiming, “She refused to take off her nose ring, so she is now sat in isolation until she takes it out. I wonder how long until she’ll crack.” This child spent almost two entire days there until she “cracked”. Taking a child out of lessons and forcing them to sit in silence in isolation over a nose ring is a stupid and disproportionate response. There are better ways to earn respect and authority than the threat of sending a student to a room to be miserable.

I remember distinctly the moment when I was teaching a Year 10 class about dystopian literature. We were looking at an extract from Kass Morgan’s The 100. The main character is called Clarke, and the book opens with her being summoned from her prison cell to see a “doctor”. The guards at the prison refer to her as “Prisoner number 319”.

As a class, we had a discussion about why they call people by their prisoner number rather than their name. The class concluded that it was because they wanted to take away Clarke’s identity: to dehumanise her.

One of the students in my class was, to put it gently, one of the more regular visitors to the school’s isolation unit. Jade (obviously not her real name) raised her hand, a smug expression on her face, and said, “That’s what they do in isolation, sir.”

“I beg your pardon?” I replied.

“In isolation, sir, they don’t call us by our name. They call us by a number.” In a mocking voice: “‘Oh, looks like number six is late coming back for break.’ Stuff like that. It is almost like they’re trying to dehumanise us, sir, by taking away our identity. You could even say it was like they were conditioning us for prison.”

Needless to say, I was delighted that she was taking such a keen interest in the text. However, I was slightly heartbroken that such a wonderfully bright student was treated so cruelly, by being reduced to something so terrifyingly akin to a victim from a dystopian novel.

Easy fix

Another thing that shocks me about isolation units is the demographic of the students who end up there. One school refused to give me the data for their children in isolation units until I filled out an official freedom of information request, at which point they begrudgingly surrendered the data, as was their legal obligation.

To no surprise at all, there was a disproportionate number of pupil-premium, English as an additional language and special educational needs and disability students in the isolation unit. Students who are already disadvantaged are then further disadvantaged by being taken out of their lessons and put into conditions that have an impact on their emotional wellbeing.

I think that, as teachers, we can sometimes see sending a child to isolation as an easy fix for our problems (and they often are). However, we need to take a step back, look at what an isolation unit actually is, and reflect on whether it is in keeping with our beliefs and values.

The way I see it, isolation units are a cruel and draconian form of punishment, and teachers across the country are turning a blind eye, because the quick fix they offer is just too convenient. Perhaps it is about time we started looking at the cost these rooms have on the wellbeing of the students who are condemned to sit in them.

Guy Doza works as a professional speechwriter in Cambridge. Before training as a teacher, he wrote for politicians, scientists, business leaders and CEOs

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters