- Home

- ‘Judging a school’s achievements on Thursday’s GCSE results alone would be unjust’

‘Judging a school’s achievements on Thursday’s GCSE results alone would be unjust’

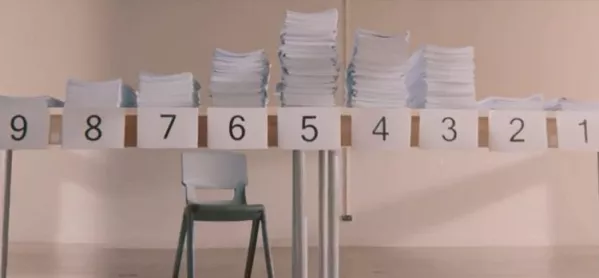

Picture the scene. It’s Thursday morning. A GCSE student bursts into the kitchen to give their parents the good news about their results.

16-year-old: “I’ve got a six in maths and a five in English!”

Parent: “Wow! That’s brilliant! [pause] Tell me again what that means…”

This week parents up and down the country will be trying their best to explain to friends and family what their child’s new GCSE grades equate to “in old money”.

As with decimalisation in 1971, many will be left uncertain as to what the true value of our new coinage is. Worryingly, as Tes revealed last week, the majority of parents appear unclear as to how the new grading system works and what a good pass is. Many employers appear to be none the wiser either.

The government may insist that they’ve been busy laying the groundwork since 2014 and that this change has been explained to parents and employers on numerous occasions. But while they may indeed have spoken, they’d be wrong to assume the message has landed. The onus has now predictably shifted to schools to ensure that those receiving results know what these new grades mean for them, and in turn that these young people are able to explain it all to employers raising an eyebrow over the CV they’ve just had placed in front of them.

It will be tempting to join the chorus of disapproval of this change over the next few days. However, the move from letters to digits may well be the least of our worries. Schools are dealing with unprecedented reform of all national qualifications. New subject content and the move back to linear exams have necessitated a very different approach to teaching and learning. The government is relying heavily on schools to implement the reformed GCSEs properly, and yet school leaders are finding themselves worrying about what might happen to their careers if this year’s results don’t look right to governors, Ofsted or RSCs. That can’t be right.

- When is GCSE results day 2017?

- How to support your students on GCSE results day

- How to tell your exam results day story: A guide for headteachers

Schools trying to offer the right curriculum for their students are restricted by the unnecessary straitjacket that is EBacc and the high-stakes accountability measures attached to it. It’s clear that the EBacc is narrowing the choices schools can offer and compromising their efforts to make sure each student can study the subjects that are most appropriate to them. The government has already dropped its requirement from 90 per cent to 75 per cent, proving how arbitrary it is. The NAHT headteachers’ union would like to see the EBacc requirement abandoned altogether.

The policy of double-counting English in the Progress 8 performance measures only when students have taken both language and literature is truly nonsensical. If an individual subject is worth counting twice then this should stand irrespective of what other subjects are taken. It is plainly wrong to use the prospect of a better ‘score’ as an incentive for schools to push uptake of English Literature. Any fall in pass-rates in English literature is likely to be as much about the mismatch of student-to-course as an indication of increased rigour and challenge. This is simple to change and it needs to change.

A narrow set of performance measures has never been an accurate way of determining the effectiveness of a school, yet it is data alone that drives performance tables, accountability and intervention. Very little, if anything, can be inferred from a single year of data. We’d recommend, and others have agreed, that three-year rolling averages are a better starting point. But this is year one of introducing the new GCSEs and a new grading system. It’s not possible to create a three-year rolling average as there are not three years of comparable data. It would be completely wrong for school leaders to find themselves under the spotlight if results this year don’t look favourable.

Much wider and richer sources of information, evidence and experience exist in every school, and NAHT expects all those who seek to hold schools to account, including Ofsted and RSCs, to look at this and not just the data arising from statutory assessments and national examinations.

The judgement of a school’s success or failure on the basis of performance data alone is unjust and unreliable. It should be seen only as a starting point. And so it is with young people. Straight-A (sorry, 9) students won’t necessarily make the best employees.

Statutory assessments and national examinations will never be able to capture all aspects of a pupil’s progress or all the different ways in which a school contributes to the progress a pupil makes.

Let’s remember that on Thursday.

Nick Brook is deputy general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union. He tweets as @nick_brook

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters