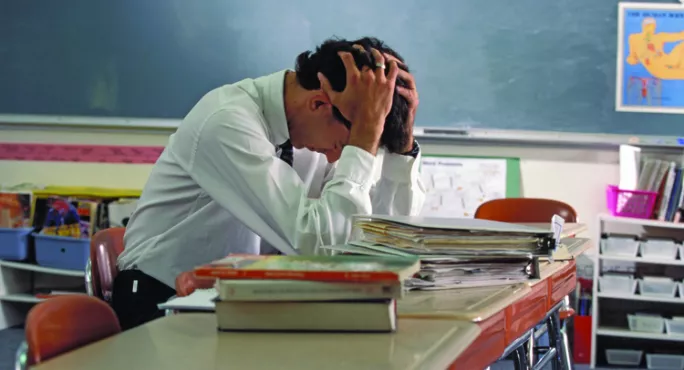

A colleague recently told me that education was in for “a seminal year”. He was echoing the thoughts of thousands of teachers up and down the country when he said that he was unable to keep up with the workload expected of him.

He said that he still loved the involvement with the pupils, but that was now largely lost in “the rest”.

Workload has, despite all the rhetoric from the government, become worse - something we all know.

I now visit a wide variety of schools regularly. They have many differences, but they all have one thing in common: the staff say that they cannot carry on like this.

A recent survey of 4,000 teachers supported this view. Some 82 per cent of those interviewed said that the workload expected of them was unmanageable. A recent EPI report found that teachers in England work longer hours than peers in most other countries, with a fifth of teachers in England working 60 hours or more a week. This is unsustainable.

The effect on teacher wellbeing is there for us all to see, and 73 per cent of those interviewed said that their health had been affected. Whatever happened to the search for a work-life balance?

Fair workload

The recent ”Fair Workload Charter” from the Nottingham Education Improvement Board has suggested that teachers should do no more than two hours’ directed time, and leaders no more than three. They have also suggested that high-quality schemes of work be provided so we can stop the hours spent on pointless planning. In addition to these very sensible ideas was the suggestion of clear policies on what student work should and should not be marked. I know that in the secondary schools I visit, the teachers would particularly agree with this.

Finally, there should be an annual review of workload policies and practices in every establishment.

The problem with very laudable ideas such as these is that they don’t seem to get off the ground. Everyone is now so consumed by accountability that we have forgotten all this planning and marking should actually be of benefit to the child. We have teachers who think that if they don’t mark for three hours a night, they are not doing a good job.

This has to stop.

Corrosive commitment

Teachers are reaching - or perhaps have reached - a point where this level of work commitment is becoming corrosive. Children do not benefit from overworked teachers. This level of work is not improving schools, but it is wrecking lives.

This year, this level of work has failed once again to result in a pay rise commensurate to the workload. The 1 per cent rise will make teachers feel unvalued. They also know that they remain without a voice.

The next year will also see the recruitment crisis worsen. Why? Well, graduates will see the pay and the conditions of service and seek alternative employment.

We will also see schools having to continue with a worthless testing regime and even more cuts that will affect all areas of education.

So, here we are starting that seminal year: perhaps it will be the year when the small cracks in the system widen to create the earthquake we can all see coming.

What good will that do our pupils?

Colin Harris is a former primary head and is now supporting teachers and headteachers

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook