Douglas Robb, headmaster of Gresham’s, caused a flurry with his blog last week accusing today’s mollycoddled young people of possessing an underlying sense of entitlement. He blamed schools (presumably not his own) for failing to engender grit, creating a generation in which everyone thinks they are special, unwilling to contemplate starting out on the lowest rung of the career ladder.

Put aside the economic and social anachronisms implicit in the idea that young people should expect to progress from “tea lady to typist…from floor sweeper to factory foreman”. It ill behoves us oldies to criticise young adults for failing to behave in the way we like to think we did. The adult world they are entering is vastly different from the one we faced several decades ago.

Far from being complicit in creating complacency, teachers today work hard to prepare young people to aim high, to challenge obstacles based on class, gender and ethnicity, and to expect all doors to be, if not open, at least not bolted shut to those whose faces don’t fit. We should be proud of supporting young people to believe in themselves. Obstacles remain, and in any case, not everyone succeeds - which is why schools don’t teach entitlement; they teach aspiration, buttressed by resilience for when things don’t turn out optimally.

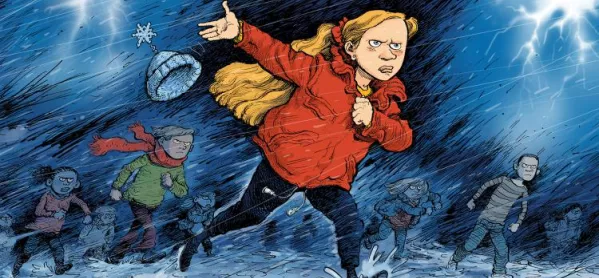

Robb’s comments would be little more than banal banter were it not for the fact that it reflects and reinforces an insidious trend of millennial-bashing, perfectly captured in a broadside book called The War on the Young, by John Sutherland. He adumbrates the key challenges facing today’s young adults: student loan burdens that will last a lifetime, and jobs that certainly won’t; general economic uncertainty; a longer working life and lower pensions; the increasingly remote prospect of home ownership, and its corollary, extended sojourn in the parental home. And that is before we start stressing about climate change and an impending energy crisis.

This dystopian new world was created by a generation that grew up, in the decades after the Second World War, at a time of unprecedented prosperity and promise. People really had “never had it so good”. Standards of living knew only one direction, social mobility broke down barriers, and it was reasonable for each generation to expect to improve on its parents’ circumstances. It is unfair and unconscionable for the generation that benefited from that unique historical conjuncture to turn its fire on today’s youth for their lack of resilience and moral fibre.

Sutherland shows that the rules are still made by the old, who continue to stack the odds against the young, requiring them to delay their own retirement in order to pay the taxes to support the much more favourable pensions of their elders. At the last election, proposals for older people to pay more towards their social care were condemned as a ‘dementia tax’, and quickly dropped. Yet just 6 per cent of the NHS mental health budget is devoted to childhood and adolescent mental health services.

A consensual society needs the next generation of young adults to be bought in, not frozen out.

Kevin Stannard is the director of innovation and learning at the Girls’ Day School Trust. He tweets as @KevinStannard1

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook