Last Friday afternoon I ended up chatting to a teacher on the South West Trains journey to Dorset. I could tell straight away that she was a teacher. She sat down and immediately got on with her marking.

She told me about one of her colleagues.

He taught every lesson direct from the textbook. Pupils take it in turns to read out from the textbook paragraph by paragraph. He rigorously drills them in the text and they do well in the tests. The pupils, by and large, don’t mind as long as they do well in the exams.

I then found this article in the Washington Post by former venture capitalist Ted Dintersmith. He became interested in why “patently qualified people often proved hopeless in the world of innovation”.

He had an experience as a parent where a teacher said to him: “Throughout school, these kids will need to take standardised tests. We need to prepare them properly. Open-ended questions can confuse them.”

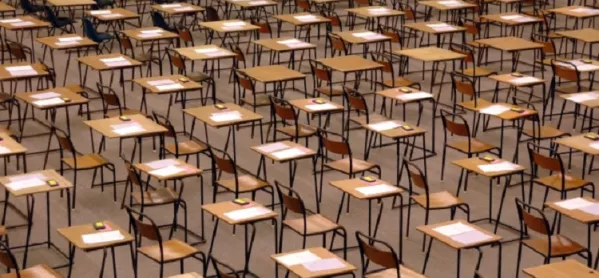

He ended up on a mission. He visited a lot of schools, categorising what he saw on the basis of what was: irrelevant, preparing kids for life and impairing life prospects. He describes what he found: “Teachers and students described to me endless additions to content, baffling new standards, and relentless high-stakes standardized tests of low-level cognitive skills. Our nation is hell-bent on catching Singapore and South Korea on test scores - a goal those very countries have concluded is nonsensical.”

Most striking was an experiment by one of the best high schools in the US, Lawrenceville School. They asked pupils to retake simplified exams in September, of tests that they had scored an average of 87 per cent in June. The results were an average of 58 per cent and “not one student retained mastery of all key concepts they appear to have learned in June.”

It is a great article that then discusses the examples of great teaching and learning that leaves behind the diet of standardised testing and matching teaching to the requirements of the exam board and the policy maker. It must be a relief to him that President Obama has called for a limit of 2 per cent of classroom time spent on testing in US schools.

Meanwhile, here in the UK, Nicky Morgan’s direction of travel in her Policy Exchange policy speech was very much the other way. She announced “robust and rigorous” assessment of pupils at the age of seven. Beyond the financial cost of this, with only one or two exam boards capable of doing this work, there are real questions of efficacy.

Will more testing work? Is there any evidence that it will improve the learning of children? It may improve their ability to pass tests, but is that the real purpose of school?

When I tweeted the Washington Post article I had one response from Zoe Elder, pointing to her recent blog on a related topic of a more relevant curriculum that better links skills acquisition and knowledge expertise. It included this lovely video, that is worth the ten minutes to watch it to the end.

The video, by Tiffany Shlain, tells a wonderful story of empathy and Ebola. In doing so it reprieves some of the themes of the Washington Post article, the need to reassess the purpose of schooling in the context of our rapidly changing global economy and society.

We will be exploring these themes next week on day two of the Whole Education conference.

In the meantime I hope that whatever we do we make it impossible for teachers to succeed by reading out textbooks. As I discussed with the teacher on the train, sociology GCSE can instead be a class that empowers young black girls or white working class kids to understand the context of their anger and disaffection, and to channel that energy on positive change. In doing so they will pass some tests, because school suddenly makes sense.

Jim Knight is chief education adviser to TES Global