- Home

- ‘A National Education Service is good in principle’

‘A National Education Service is good in principle’

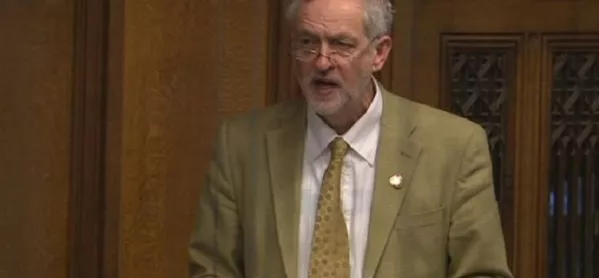

Lots of Labour ideas would have an impact on our sector if the party came to power. For example, the free universal childcare pledged by Jeremy Corbyn could, depending on the detail, encourage more people into work and learning. It could, in the longer run, pay for itself.

However, it is their proposal for a National Education Service that grabs most attention in my book. The idea is that learning throughout life is increasingly crucial and should be an integrated service. Rather like the National Health Service, it should be free at the point of use and not based on ability to pay.

It would be backed by hefty additional investment of around £13 billion per year, which Labour said it would find by reversing recent cuts in corporation tax. The bulk of it would go toward removing university tuition fees which, given the nature of the current system, will most benefit higher-earning graduates. Nonetheless, further education and lifelong learning would definitely benefit after years of cuts, to the tune of £2.5 billion according to Labour’s 2017 manifesto.

Ideas about lifelong learning

But beyond extra (welcome) investment, what would a National Education Service mean? There’s lots that’s not yet clear, though perhaps that’s not unexpected given the point we are at (at least in principle) in the electoral cycle. The general election isn’t due until 2022, though we’ll see what happens in practice…

In fact, Labour has said it will establish a Lifelong Learning Commission to generate ideas. Learning and Work Institute looks forward to contributing to this. In that spirit, here’s three things I think the development of the National Education Service should consider, building on a recent Fabian Society pamphlet that I contributed to.

The first is to look at people’s motivations to learn and inspire more adults to learn. Our recent research on how adults make decisions about learning shows the reasons are complex and the most commonly cited reason for not learning is lack of interest or not seeing the relevance. So a National Education Service needs to link with local services and groups, as well as employers and trades unions, to inspire more adults to want to learn.

Cost of learning

The second is to consider all the costs of learning. On top of course fees, people may face travel costs, costs of books and materials, possibly time off work, the opportunity cost of the time spent learning, etc. How will a National Education Service help people mitigate these costs? It could aim to further increase the amount of online learning - what would a blended learning approach look like? It could offer maintenance support to some groups, perhaps as a means-tested loan - how would it target this help?

Similarly, how will a National Education Service engage employers? Could that be through reforms to the current right to request time off to train? How do we inspire a culture of learning among more employers?

The third is to design the service around individuals. I think sometimes we forget that public services are meant to be services for the public, and instead expect people to fit around funding rules and government policy. A National Education Service will need to think about how all the building blocks fit together. How do apprenticeships and T levels fit into this picture? Given forthcoming devolution of the adult education budget in some areas, how “national” would the National Education Service be? Personally, I’d see it as a framework of entitlements that can be joined up and added to by local authorities.

Increasing participation in learning

The principle of a National Education Service is a good one. Given an ageing population, global change, and all the benefits we know learning has, it’s vital we increase participation in learning. That’s recognised across the political spectrum.

The question now is how we do it. That will require investment and fresh thought. Lots of us are ready to providing support in that thinking.

Stephen Evans is chief executive of the Learning and Work Institute

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters