- Home

- Not all children are born equal...

Not all children are born equal...

Once again, there were four of us patrolling the corridors looking for Aaron: two members of senior management, our principal teacher of pupil support and one learning support teacher. The police were also on the way, having been called because Aaron, with his history of violence, had threatened his teacher and several of his peers as he stormed out of the classroom.

Eventually, we all ended up in the same corridor, with Aaron sitting on the floor, swearing at the police, and two of us at either ends of the corridor, redirecting the parents of first years who had arrived for their “chance to chat”.

When the path was clear between the corridor and the front door, Aaron was taken away, kicking the police car as he went and shouting that he would “never come back to this fucking school”.

Of course, we all knew that was a lie. Aaron always came back. And we always accepted him back.

The following Monday, following a restorative meeting with his teacher, Aaron was sitting in the same classroom from which he had recently fled, starting yet another second chance. After a weekend of watching his mother shooting up heroin and getting close to a succession of men on her sofa, while Dad languished in a prison cell, there was never really another option for him.

And there was never another option for us. Who could begrudge giving Aaron as many chances as were necessary to turn his life around, given the inconceivably horrendous conditions under which he lived? Similar behaviour from a different pupil may have brought a different - and perhaps harsher - result but, despite his huge drain on energy and resources, when it came to Aaron the interests of fairness outweighed those of equality.

That may seem unfair. The system of comprehensive education has, as a founding principle, the mantra of equality for all.

But equality has failed. We let down thousands of children every single year because we try to give equal treatment to all. The truth that every teacher working with disadvantaged students should know is that we need to be less equal in our approach to ensure an equal opportunity at life for all.

Reasons for bad behaviour

Of course, pupils can be naughty and disruptive, no matter what their background.

I remember, as a newly qualified teacher at one of Edinburgh’s top private schools, I wandered into a history classroom where missiles flew past my head, pupils wandered about freely and nobody seemed to be on-task.

Why would they go for academic rigour when they could mess around at school with their friends and then, in a safe and supportive environment at home, apply themselves to their studies and catch up on all they had missed? Results did not suffer. Their behaviour was a choice with little reason behind it other than the fact they could do it, and it had little consequence to their lives.

In schools in more deprived areas that I have worked in, the behaviour was the same, but pupils had much more significant reasons to play up than just simply larking about.

Absentee parenting leaves few boundaries for young people to conform to - they are simply not used to being told what to do. And in many cases there is little parental or social pressure to conform and no role model to show them how to behave. Some pupils crave the attention at school that they lack at home and find they get it from playing up either for their peers or against their teachers in front of the whole class. Others have unmet needs, including anger issues and mental health problems (not least of which is clinical depression). Any of these may manifest in disruptive behaviour.

These children don’t make a free choice. Their situation defines their action. And unlike their more affluent peers, their misbehaviour does impact them academically.

Providing these children with equality of opportunity and expecting them to improve because they can study for the same exams as their more affluent peers is a nonsense. In these areas live the children who enter primary education already 18 months behind the highest performing four- and five-year-olds, who come from families who do not own a single book and who, because of multiple siblings and young parents struggling to cope, have been over-stimulated by hours in front of a television from an early age.

By secondary school, they may be missing large parts of their education because they live as part-time carers or because, like Aaron, their life outside of school is too complex and chaotic. When they do come in to the safety of school they are tired and hungry (often fed by their teachers) and, in a class where their absences mean they are already too far behind to keep up with their peers, their natural defence mechanism is to cause disruption, which affects everyone and delays the progression of all.

We have consistently failed to help these children achieve academically. This year’s breakdowns are yet to be released, but attainment was lower for disadvantaged pupils compared with all other pupils across all headline measures in 2015, according to the Revised GCSE and Equivalent Results in England, 2014-15. In the accompanying notes, the government reports that “the average position of disadvantaged pupils compared to others remains similar to that in 2013.”

In 2013, 37.9 per cent of pupils who qualified for free school meals (FSM) got five GCSEs, including English and maths, at A* to C, compared with 64.6 per cent of pupils who do not qualify.

If we go back as far as 2008, across England as a whole, 40 per cent of children eligible for free school meals obtained five or more GCSE examination passes at grades A* to C, compared with 67 per cent of those not eligible for free school meals.

Go back further and the metrics may change, but the fact remains: disadvantaged kids have always done worse than their peers.

We’ve tried numerous ways to close the gap. We are better schools than we were.

In general, teachers are better paid and better trained and, in many cases, more motivated, and, until very recently, they were better resourced and had more of a say in how the curriculum developed and what children should be learning than previously.

We are now much more aware of how our students are performing, and much better at measuring them and understanding the implications of any intervention.

We have tools like the Education Endowment Foundation’s Toolkits, which give us best practice on how to intervene to ensure all our students achieve. And we are more informed about research than we have ever been.

We are better at safeguarding and our pastoral teams are better. Schools are hubs of social care and intervention. We step outside our gates and sometimes our professional boundaries to try and ensure that the system can work and barriers are removed.

We’ve spent around £2 billion of pupil premium money. There’s countless more cash in the form of time and intervention from charities dedicated to closing that gap.

I could go on. By almost any metric we are better set up to provide equality in education than we ever have been. And the impact is minimal.

But one area we have not looked at properly is behaviour. Not really. Not in the way I think we need to.

Most schools have a fairly solid behaviour-management policy and try to adhere to it rigidly. It’s what Ofsted seems to want, it is definitely what the government wants, and it is what is expected, largely, in society.

We need to be less equal in our approach to ensure equal opportunity for all

We are obsessed with fairness. And we are obsessed with not letting people “get away with it”. In a narrative similar to that against welfare, we worry of being taken advantage of - if a child knows they can do something and blame their situation, then that is what they will do. We can’t let them get away with it.

That’s where “no excuses” comes from - the refrain of many a school now. What it comes down to, essentially, is that children should be able to block out everything they experience outside of school and it is a school’s duty to impose the boundaries that those students are missing. It is based on a belief that schools can change a child’s behaviour by enforcing a strict adherence to the “rules” during what amounts to a relatively small proportion of their lives.

And is this approach successful?

As John Tomsett, headteacher at Huntington School in York, has noted in his blog, the relationship between teachers and pupils is too nuanced for such an “inflexible” approach and it further disadvantages some of our most vulnerable children.

How many disadvantaged children fail academically because they are out of class thanks to fixed-term exclusions, or have dropped out of the mainstream system entirely because of permanent exclusions?

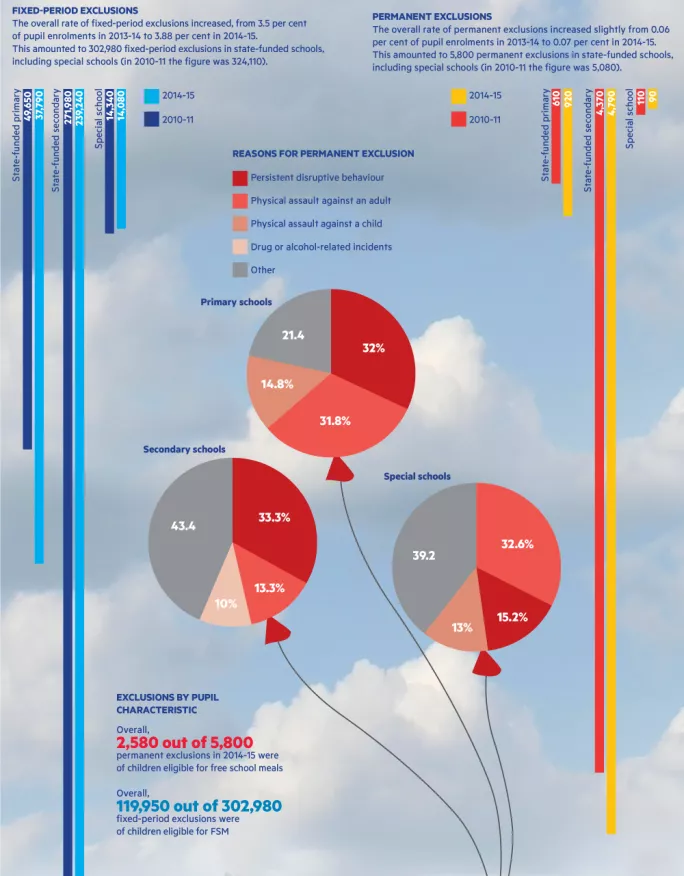

Pupils in England with special educational needs or those receiving FSM are much more likely to be excluded from school than other children. In 2014-15, those with FSM eligibility were excluded four times as often as those who were not eligible, while those with identified special educational needs and disability (SEND) were seven times more likely to be sent home.

Although these latter figures have shown a slight improvement over the past five years there has, in effect, been very little change (see graphic, above).

And how many children with undiagnosed SEND or who are on the cusp of FSM are labelled disruptive and make up a large cohort of the remainder of those excluded?

It is time we admitted that a blanket “equal” approach is unfair, as all children are not equal. I would argue not that we need to make excuses for these children, but that having a better understanding of their context and adapting for that may do more to close the gap in attainment than any extra funding that is in reality a cheap plaster on what is a social - not necessarily an educational - sore.

“No excuses” does not change the behaviour of these children. Some may be “saved” from themselves, but for the majority it is a different story.

Sometimes, you get a temporary conformism at school but outside there can be little impact.

And if they don’t conform, those who manage to avoid exclusion spend so much time being disciplined in pointless, punitive ways that they have very little chance of academic success - they are not going home, as those independent school boys at my first school did, to parents or tutors talking them through the course content and forcing them to catch up.

The ‘middle way’

It is wrong to suggest that any alternative to the no-excuses approach endangers staff and the learning of others. I am not arguing for a blanket amnesty on bad behaviour by those who are classed as disadvantaged. There is a middle way and all good schools in deprived areas should adhere to it.

At the school I lead, in an incredibly deprived area, we have strict rules. Discipline for Learning involves several progressive steps that all pupils are aware of and a robust system they can expect to be dealt by. Three offences and you’re out of class and sent to a partner department or, for more severe infractions, you are sent to principal teachers or the senior management team.

For the most part it works well. But there is an understanding, one that is clearly communicated by me and bought into by the staff - that there are always exceptions to the rule. Our children are not equal and our teachers recognise this.

Mhairi may have had her mobile phone out in class, but it was more than likely she was just checking to make sure her gran, whom she cares for, had managed to get out of bed that morning.

Alex may have come in half-dressed and with none of his books, but that’s because he was taken from his home in the middle of the night because his violent, alcoholic father had paid the family a midnight visit.

We don’t punish in these situations, but neither do we ignore. A quiet and sympathetic word in these circumstances may work far better than the full force of an inflexible system. If we enforced the policy we would not change their behaviour. We would damage the relationship, we would make their situation all the more difficult and, ultimately, we would have failed them.

A blanket ‘equal’ approach is unfair, as all children are not equal

Year on year, it appears that schools are taking little notice of pupils’ individual circumstances and judging them all by the same standards. There is a constant refrain that “they would not get second and third chances when they are working/talking to the police/up before the judge”, but this is a ridiculous argument. If we cannot give children extra chances to learn from their mistakes when they are still children (and, yes, that includes 16- to 18-year-olds) then when will this be available to them?

The time has come to abandon equality and concentrate on fairness (or equity) to redress the balance. Let’s treat these children differently - give them extra chances, extra resources, extra time. Let’s dedicate ourselves to giving them equality of opportunity by giving them more of our time and support than those who need it less (or who get it from the wider support systems they have at home).

Let’s have more nurture rooms where we could send Molly - fresh from a sleepless night caring for her siblings and her drunken mother, arriving in school tired and hungry only to tell a member of staff to “fuck off” when asked why she hasn’t brought a pencil - instead of excluding her for days until a parent can come in to discuss her readmittance.

The resources need to be made available for one-to-one support for Kieran so, rather than sending him home to stay up all night playing Call of Duty and getting further and further behind with his maths, he can be isolated from his classmates and given chances to get up to speed with his studies.

What will other pupils, and indeed teachers, think of this differential treatment for the most vulnerable pupils?

I believe that other children know and understand - sometimes more perhaps than the adults who teach them - that some of their classmates need a bit of a break. Social media gives them more access to the lives of others than most of us could ever imagine.

Meanwhile, most teachers in schools located in areas of multiple deprivation are only too aware of the circumstances affecting their children and make multiple adjustments to their views of behaviour management on a daily basis to ensure, as far as possible, that these children stay in class and get an education.

Of course, there will be those that this approach will enrage. “It’s not fair!” they yell.

But it’s not fair that young people have to endure a background that is no fault of their own. Real fairness is an equal start in life. Only when we target pupils such as Aaron with a sense of this real “fairness”, rather than trying to ensure equality for all, will we begin to see a society where everyone is valued, has a purpose and can contribute to the growth and development of all.

The writer is a headteacher in Scotland who wishes to remain anonymous to protect the students they teach and the community they serve

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe using the link below to read many more like it

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters