There are three certainties in life: death, taxes and seeing that picture of a monkey, a goldfish and elephant being asked to climb a tree at a CPD session on differentiation.

The presenter usually thinks they’re being hilariously edgy and original, but really they’re having to bat away eye rolls from every corner of the room.

Despite the audible groans, wry smiles and teachers resigning themselves to the fact that they are about to sit through exactly the same talk they’ve sat through before, the message behind that picture has never been so important.

Teachers are constantly told that we must meet the needs of every pupil in the room by offering a choice of task, targeting questioning and planning a variety of activities into our teaching.

But when it comes to assessment and exams, it’s a matter of “Differ-renchy-what? Non, non, non, mon frère. We’ve got no place for your fancy words round here.”

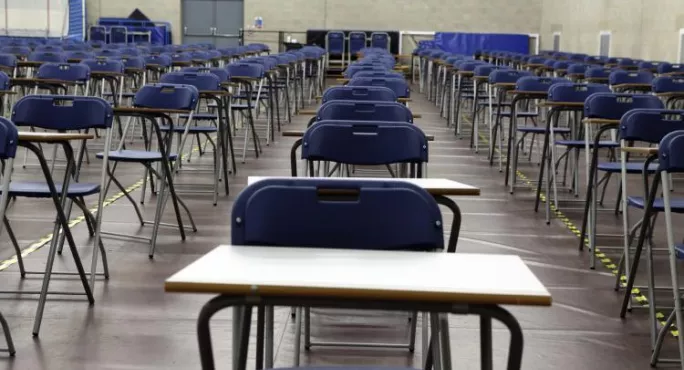

A couple of hours in extremely pressurised conditions

Our teaching system is set up to cater for as many different learners as possible. But our exam system really does ask those with varying skillsets and talents to all be measured and assessed in exactly the same way.

Two or sometimes three years of a pupil’s education hinges on a couple of hours in extremely pressurised conditions. And, if they buckle, well, that’s it. It doesn’t matter what the hell they were predicted, or how hard they’ve worked, or how many outstanding pieces of work they’ve produced during their course, they’ll be sucked into the cycle of retakes.

And why does this happen? Because Michael Gove, a man whose experience of education is that he once attended school, and the coalition government thought it’d be a pretty neat idea.

I’ve lost count of the number of pupils I’ve taught who understand the intricacies of Shakespeare, can dexterously apply linguistic theory, who can marshal a class debate like an experienced veteran, but just crumble when it comes to exams. Not because of a lack of knowledge, not because they can’t do it, and most certainly not because they just didn’t try, but because our exam system places so much pressure on children that they simply can’t cope.

Inspiring a genuine love of learning

Last week, as a reaction to the closure of schools because of coronavirus, the government announced that GCSE and A-level exams would be cancelled. Grades will be awarded from a combination of a range of factors including teacher assessment and non-exam assessment. Schools will not be judged on their results from this academic year in any subsequent Ofsted inspection.

It is absolutely imperative that we get this right.

I once worked at a school whose safeguarding policy was genuinely underpinned by the statement: “The best pastoral care you can give a child is an outstanding set of exam results.” Well, they may turn up to their exam malnourished, tattered and exhausted, but at least they turned up, eh? Each bum on a seat is a boost in the league table, isn’t it?

What’s really important is inspiring a genuine love of learning and ensuring that pupils have experienced and learned about a broad range of issues and topics throughout their school journey. School isn’t the end of a child’s education - stamped with a GCSE or A-level exam - but the beginning of an intellectual curiosity that will last a lifetime.

This news could be a gateway to a more equitable system, which judges pupils holistically, rather than on a few nervous hours spent in an exam hall. We now have an opportunity to reduce pressure on pupils, so that they get the grades they deserve.

Yes, I’m sure there will be some kinks to iron out. But if this approach to awarding qualifications proves fruitful and fair, it could set a precedent for years to come.

Paul Judge is a secondary English teacher, working in the North East of England