Yesterday afternoon I interrupted a meeting at work to take a call from my nephew. He doesn’t ring me very often but he wanted to tell me himself about his AS results. I am delighted his hard work has paid off.

Meanwhile Facebook notified me about my “memories”. I found that on 14th August 2008 I posted at 1.57pm that I was “saturated with media bids on A-levels”.

In all of those media appearances as minister it was compulsory to begin by congratulating all the students and their teachers on another excellent set of results. I do so again, sincerely.

But I also thought it was time to delve back in to this year’s Joint Council for Qualifications data and see what I could find.

First, it was great to see the increase in numbers taking maths, further maths, physics and computing. These subjects are critically important in underpinning the sort of skills employers want. Alongside the rising unemployment stats this week, the number of vacancies also rose to 735,000.

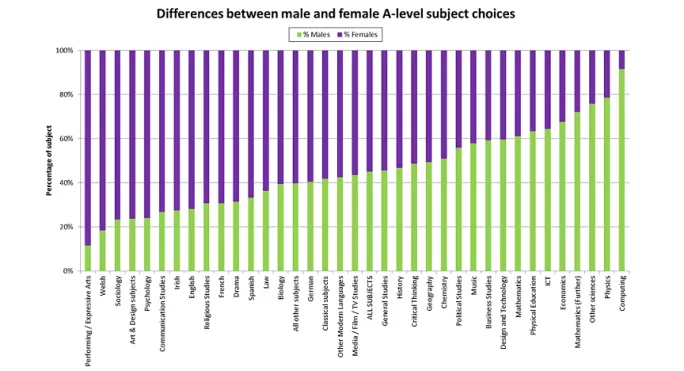

But then I noticed this interesting graph:

This tells us a number of things, including:

- More girls took A-levels than boys.

- Boys are much more likely to choose the Stem subjects.

- The only sciences that are more appealing to girls are psychology and biology

I then had a look through the data comparing entries by gender with 2013. Here I saw the number of girls choosing maths was actually falling and that the number of girls taking computing was as low as 456, compared to 4,927. This is despite 28,000 more girls taking A-levels than boys.

This is less good news.

UK employers and the British economy can not afford this loss of talent. The digital economy is growing fast. While it will require plenty who come via other subjects, such as designers, project managers, and marketeers, we desperately need to improve the take up of Stem subjects by girls.

What are we to do?

When I went to visit Kidzania at the beginning of the week, I was interested to be told that they initially had a problem attracting girls to try the activities in the Renault motoring experience. They solved this by having more women staff working in that area, leading the engineering.

Then I found this article “Girls do better in school when taught by women”. This study shows the significant effect on girls’ performance in South Korea when taught by women.

But if only 300 girls take computing at A-level, how are we going to get enough women confident enough to teach it? There are some great subject knowledge enhancement courses to convert biologists to shortage science subject teachers, but they do need some prior attainment in the subject.

One other thought was stimulate by this piece on maths teaching. This tells the story of David Wees, who said:

‘There’s lots of evidence that what we think about is what we know later. I want to increase the amount of thinking going on in math class.’

By focusing on helping learners make sense of a problem rather than just getting the right answers, he seems to have created a much more engaging and effective experience for learners.

Is this solution scaleable? Do teachers here have time to develop this pedagogy alongside the pressure of high stakes accountability?

I don’t pretend to know the answers, but I would love to make sense of the problem of the gender divide in Stem education.