Last week I wrote about the A Level results in England. I worried that the gender divide in Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects was deeply worrying in terms of meeting the skills needs of the economy. When the GCSE results were announced I was therefore keen to seen any patterns.

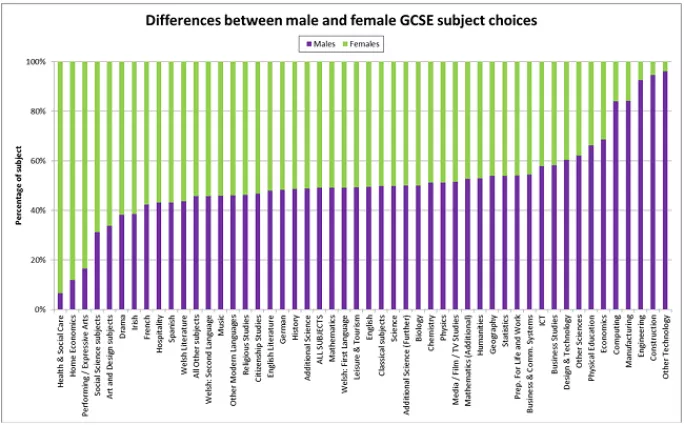

The same graph on gender divide stood out:

Last week many commented on how poor the computer science A-level is, and that girls were therefore reasonably giving it a wide berth. Computer science is now in the National Curriculum and the subject has received a welcome freshening from the examination boards. As a result, it had more than twice as many entrants this year (35,414, compared with 16,773 in 2014) - but the gender divide remains. More than five times as many boys chose this subject at GCSE.

But looking across the whole range of subjects, it is equally troubling to see what boys are not choosing.

More than 30,000 girls take home economics and only 4,000 boys. Health and social care is less popular, but of the 20,000 entrants only 1,500 are male. We know that creativity is as important to the future economy as Stem, and yet arts and design subjects are twice as popular among girls - a yawning gap of over 63,000 entries.

It is clear we have a big problem with gender stereotyping in subject choices.

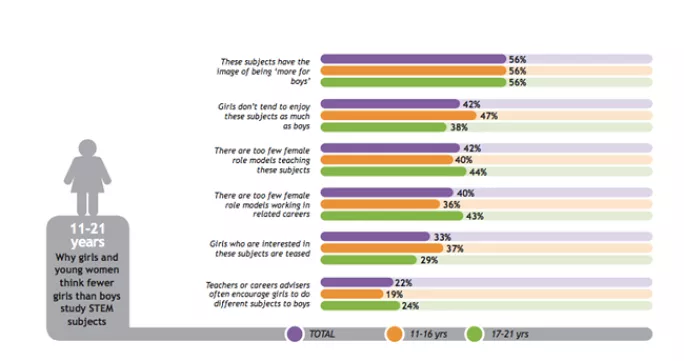

Why? This graph from the Girl Guides excellent 2014 Girls Attitudes Survey gives some indicators around girls and Stem:

It would seem it is a balance of culture, role models, poor careers advice and gender balance in the workforce. It is worth noting that the same report shows that 85 per cent of those surveyed experience everyday sexism in some aspect of their life. There is still much to be done.

But girls still significantly outperform boys. Although boys are still doing slightly better at maths, girls are winning at physics, chemistry, biology or computer science. It is much harder to find research on why boys tend not to choose subjects associated with caring and creativity, and yet it is a problem that must be addressed urgently.

The other GCSE data that grabbed my attention was the regional breakdown of performance.

I was delighted to see the biggest improvement in the North East and in Yorkshire and Humberside. These are areas with the longest tail of underachievement and their results are hugely welcome.

But the stand out performer is London. It is the best region in the country with 72 per cent getting A*-C and more than 25 per cent getting A or A*. Back in 1997 only 16 per cent gained give GCSEs at grades A to C. This is a stunning achievement by London’s schools, teachers, and pupils. I also think it is great tribute to the vision of Estelle Morris in starting London Challenge in 2003, and to Tim Brighouse, Andrew Adonis and Mike Tomlinson for leading the transformation of education in the capital.