Opinion: ‘We have a new working pattern. Now we need a new learning one.’

The jobs market is changing fast, but education isn’t. As a result of globalisation and technological change, a new social contract is needed between the state and the individual - with massive consequences for education.

My dad went to grammar school. He trained as a chartered accountant doing his “articles”. He remained an accountant until the day he died. His education and training equipped him for a job for life.

I am currently enjoying my fourth career in my fifties. My generation was the first in my family to go to university. We managed to get into home ownership before prices went out of control. Our worries are whether our pensions will be enough in our old age, how old we will be when we retire and whether living to our nineties will bring with it unaffordable care needs.

But the future is now less certain for young people, both in and out of work.

School trained them to pass tests. University started to get them thinking, but although there may be work, there are few careers. Employers want recruits with skills and as creative thinkers, not people who are good at passing tests - they use technology for knowledge regurgitation.

Then this week Ernst & Young announced that they are missing out on too much diverse talent and so will stop filtering applicants by qualification. It seems that, despite the debt of a degree, its value as a qualification is diminishing.

The pattern is emerging of a much longer working life covering many “careers”. The final salary pension is no longer affordable as we expect to live into our nineties, and we therefore can expect to be working well into our seventies.

This series of articles discusses how our dependency on health, welfare and pension services; our demand for education and our contribution through taxation looks like it will change.

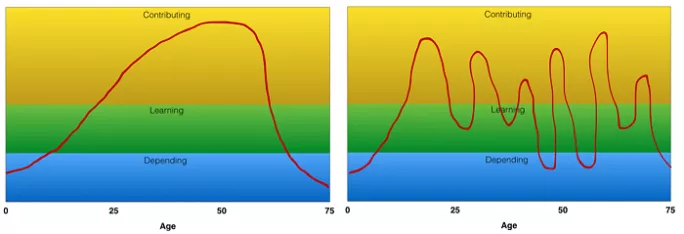

The graphs above show how we are moving from a smooth curve - leaving education, entering a working life of paying in and when in retirement drawing out - to one where we dip in and out of learning, welfare support and earning.

The implications of this could be huge for education.

The argument for moving away from school teachers filling pupils with content and then testing them is well rehearsed. It now looks more compelling than ever to instil a love of learning, and to coach learning. These learning skills will be for life, in a much deeper way than when the phrase lifelong learning was in common use.

This new pattern of working life could be good news for further education. If we need to dip in and out of education it will often be to learn new skills at the local college. As University Technology Colleges and studio schools show the way to new forms of work-related learning, it is possible many more of us will learn in this way.

The biggest change is likely for universities.

If more big graduate recruiters follow the lead of Ernst and Young their effectiveness in training for the jobs market will be sorely tested. What is to stop people doing a series of free massive open online courses to gain some of the knowledge and competences to get through the Ernst & Young process? With degrees costing more, people will look for new ways of getting the next well-paid job.

More positively, if changing jobs creates a need for new thinking could we revisit the higher education model? Would it make more sense for many school leavers to go to college to get more work-related skills and wait for university. Could four years of student loans be drawn down over a working life? Could universities re-discover themselves as centres of thinking and reflection rather than being the end of the education funnel that filters for high value employers?

Having just returned from a mentally refreshing three days on a university campus with 150 like-minded bright digital entrepreneurs, I am attracted to a working life that embeds a university experience into the normal pattern of my year. Could that be the future?

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters