An unremarked lexical outcome to the heightened state of awareness of terrorism has been the conscription of the term “radical” to describe someone holding extreme views, and posing a danger to civil society.

The Prevent strategy is aimed squarely at terrorism, but government guidance uses the term “radicalisation” to describe the process by which individuals are drawn in to support violent extremism. In this context, teachers and schools have a duty to pre-empt “radicalisation” through a balanced curriculum and attention to Fundamental British Values.

For centuries, to be “radical” was to be on the more “advanced” wing of the broad coalition of forces ranged in opposition to the hierarchical, aristocratic “settlement” that prevailed in Britain at least until 1832, and arguably well beyond. Self-identified Radicals contributed - occasionally losing their liberty or their lives - to the creation of liberal democracy. It is unfortunate that the term has now been enlisted to describe those who, from left or right, whether secular or sacerdotal, seek the violent disruption and defeat of liberal democracy.

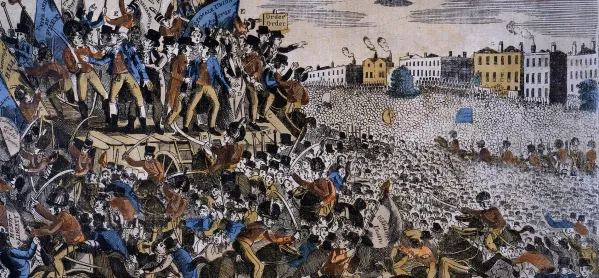

The film Peterloo reminds us of Britain’s radical history. Historian Katrina Navickas observes that, while the casualty toll was relatively small, the events at St Peter’s Fields in 1819 rank with Amritsar, Sharpeville, Soweto and Tiananmen Square in terms of significant mass protests. In all these cases, the protesters would have been perceived by the authorities as radical, since their demands, while not violent, involved change “from the root”.

The Manchester protesters were calling for the far-reaching reform, but not the overthrow, of the political system. Many joined the Chartist movement, but after mid-century, most radicals joined the broad coalition of progressives in the Gladstonian Liberal Party.

Going back earlier, Oliver Cromwell and the parliamentarian rebels in the 17th century would no doubt have been considered radical, had the term been invented. Certainly the Levellers, Diggers and others on the Roundhead fringe were radicals avant la lettre. But from the time in the late 18th century when the term “radicalism” was coined, it remained fundamentally constitutional in nature.

Although radicalism as a separate political tradition died out in Britain, across continental Europe it continued to denote a strand of left-wing, non-socialist thought - taking the place of liberalism, which in the rest of Europe tended to denote right-of-centre individualistic, laissez-faire dogma rather than social progressivism. Leonardo Sciascia, novelist and excoriating anatomist of political corruption, sat in the Italian parliament as an MP for the Radical Party.

In higher education, some still fly the flag for radicalism as a vehicle for oppositional academic analysis. The Radical History Review, and Antipode - a “radical journal of geography” - continue to plough their respective furrows.

The use of “radicalisation” to describe a trajectory towards violence and terrorism does history a disservice, in ignoring the long and honourable tradition of radicalism in this country.

The Prevent guidance itself offers a get-out, though. Schools must offer a balanced presentation of political issues, and provide a “safe space” for the discussion of sensitive topics. That leaves room for teachers to explore the fact that the liberal democracy which is being defended by these provisions was created by, not least, many who proudly wore the label “radical”.

Kevin Stannard is director of innovation and learning at the Girls’ Day School Trust. He tweets @KevinStannard1