- Home

- ‘To produce more engineers, schools must focus on engineering habits of mind as well as on Steam subjects’

‘To produce more engineers, schools must focus on engineering habits of mind as well as on Steam subjects’

Most people agree that the UK needs more engineers. In fact, we’ve needed them for a while now.

Sometime in the first decade of this century, no one is quite sure when, the acronym Stem was coined as a way of solving this problem. What we needed, the argument went, was a focus on four subject disciplines - science, technology, engineering and maths - at school and university, and we would be able to grow more engineers.

Wrong. As the world-class civil engineering department at UCL has shown, undergraduates do not need to have maths or science at A level to be able to excel in engineering; it’s the mindset of students that matters more.

Wrong. As the proponents of Steam have shown, other subjects are important, too. Art and design and the arts, more generally - the “A” in Steam - have much to contribute; design thinking is, after all, very close to the engineering design process.

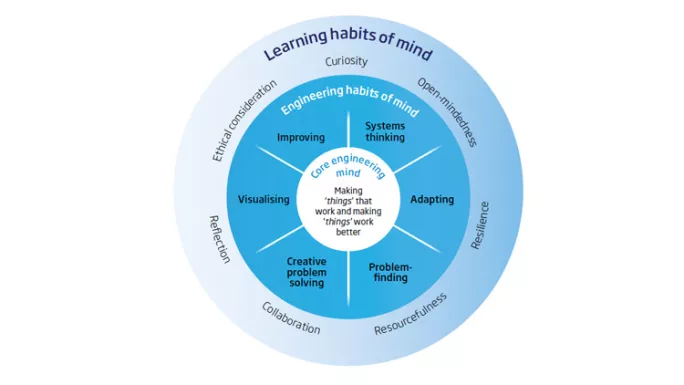

Wrong. We need to shift away from a focus on disciplinary knowledge to understand the kinds of habits of mind which engineers actually have in the real world.

These habits include systems thinking, adapting, problem-finding, creative problem-solving, visualising and improving:

This week, with the Royal Academy of Engineering, we launched Learning to be an Engineer: implications for the education system, a collaboration with the University of Manchester and Primary Engineer.

In it we describe the results of a two-year study into how schools which focus on engineering habits of mind as well as on Steam subjects find this a helpful way to promote an active engagement in engineering.

Specifically the Learning to be an Engineer research suggests that:

- Schools need to move away from a focus on Stem and Steam and develop a better understanding of the ways engineers think and act using engineering habits of mind;

- Teachers will do better when they use signature pedagogies, teaching and learning methods most suited to cultivating these habits of mind;

- We all need to build teacher capability through professional development to embed these habits into everyday teaching.

One FE college and 33 schools in Glasgow, Manchester and the south of England took part in the research, with 84 teachers and more than 3,000 pupils.

With the teachers we identified a cluster of three powerful signature pedagogies: the engineering design process, playful experimentation or what we term “tinkering” and authentic engagement with engineers. Each of these is important in the cultivation of engineering habits of mind.

With a range of professional development suppor,t all teachers managed to change their practice to move away from subject dominance to a focus on broader habits of mind.

While we believe that disciplinary knowledge is essential, our research suggests that we need to be less hide-bound by this, explicitly teaching the habits of mind and engineering capabilities that will set children and young people up for the future, making them more creative, resilient and career-ready.

These habits of mind are not exclusive to engineering but will enhance development of young people towards any career.

Engineering ‘faces a skills crisis’

Engineering is a varied profession that contributes 20 per cent of the country’s gross value added. But it’s facing a skills crisis that threatens its future sustainability.

Engineering habits of mind are vital for the future growth of the UK economy, whether they’re applied to civil engineering, hardware development or medical robotics. For engineering is rooted in curiosity, creative problem-solving, adapting and improving, all of which we see young children demonstrate.

Unfortunately, a knowledge-focused curriculum can all too easily leave these habits of mind undeveloped.

It’s time to reframe the challenge of not having enough engineers. It’s not just about which subjects they study (though Steam is a good starting point). The argument goes like this:

“If we see engineering education in terms of desirable engineering habits of mind as well as subject knowledge and clearly articulate how best these can be taught; and if we offer teachers high-quality professional learning to design new ways of teaching and working with engineers; then we can understand what schools need to do to ensure more students have a high-quality school taste of what it is to be an engineer so that more choose to study engineering beyond school and potentially become engineers.”

Even in times of very great change, schools rose magnificently to the challenge of these projects. Just think what might happen in calmer times.

Professor Bill Lucas is director of the Centre for Real-World Learning at the University of Winchester and an international adviser to the Mitchell Institute. He is the author of many books including, with Guy Claxton, Educating Ruby: What our children really need to learn. He tweets at @LucasLearn

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters