The prime minister’s promise this week to plough £1bn into razing, replacing and repairing crumbling schools across the UK is to be welcomed.

However, knowing where to begin the task ahead is crucial.

A golden opportunity lies in the small proportion of these buildings that currently pose the biggest health risk to pupils and teachers.

CLASP the situation

The 3,000 Consortium of Local Authorities Special Programme (CLASP) schools designed in the late 1950s should, therefore, be a priority in this project.

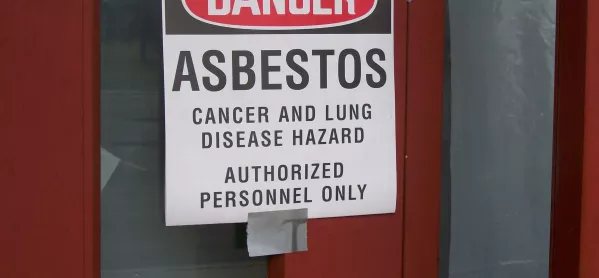

Extremely popular models in their time, CLASP buildings used light steel frames and were insulated with large amounts of asbestos in their structural support columns.

Most were only meant to last 40 years, yet remained standing long past their intended use. Even after the UK finally banned asbestos in 1999, some of them remained standing and are now approaching 70 years old.

It should come as no surprise then that, in the UK, we’re still paying the price for the huge tonnage of asbestos imported to our shores throughout the 20th century, much of which was used to construct CLASP schools.

And when I say “we”, I mean teachers, parents and - perhaps most tragically - schoolchildren.

Fixing a disaster in our schools

A recent report by the think tank ResPublica, for the campaign Airtight on Asbestos, shows that deaths in the teaching profession are rising exponentially due to prolonged low-level exposure to asbestos.

Teachers in the UK are five times more likely than average to develop mesothelioma, the fatal lung disease most closely linked to the material. Meanwhile, exposure to asbestos in the earliest decades of a child’s life doubles their risk of the same outcome.

The announcement includes £1 billion for 50 major school building projects, with a further £560m for repairs. But if the government wants to convert its praise of the public sector and improve the public’s health, post-Covid, it will need to do more.

Demolishing 1,000 of the total number of CLASP buildings still in use today would make a considerable difference to the asbestos risk posed by the UK’s total building stock.

Already we’re seeing criticism of the government’s pledge to tackle school dilapidation.

The National Audit Office has estimated that, for schools needing repairs to sufficiently improve above satisfactory level, the government would need to spend around £7.1bn, almost seven times the prime minister’s pledge.

With or without such investment to hand, the mistake now would be for the government to misdirect its attention to enhancing otherwise serviceable buildings, leaving the most hazardous schools the country has ever built to reopen in September of this year.

We must expel asbestos

We are now beginning to understand the cost of not removing deadly asbestos as part of the Building Schools for the Future programme, which came to an end in 2010.

Allowing children to enter buildings as unfit for purpose as the dated CLASP schools for another decade would be utterly shameful.

In their open letter to the chancellor of the exchequer written in April, ResPublica called for a portion of the £1bn fund previously committed to removing unsafe materials from Britain’s public estate to include asbestos in high-risk schools.

It points out that a government willing to prioritise the removal of CLASP schools could easily do so in line with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government’s advice on removing unsafe cladding.

If Boris Johnson’s government is truly poised to reverse the neglect of our educational public estate, it should proceed with the mantra: make the worst of all the first to fall.

Our priority should be clear. The prime minister must expel asbestos.

David Morris is the Conservative MP for Morecambe and Lunesdale, and has been an MP since 6 May 2010.