- Home

- School trips: the two ways they can be saved

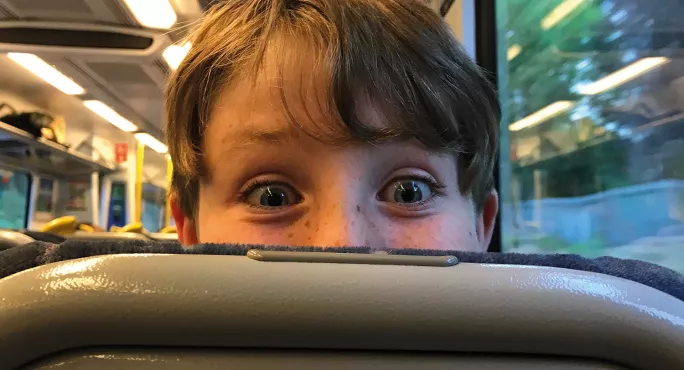

School trips: the two ways they can be saved

It is the start of the school day and I am going through my emails while drinking a hastily prepared mug of coffee.

As I filter through messages about data analysis (red star that), parent communications (best dealt with when you are not in a rush), and duty rotas (will I eat at all today?), one email catches my eye. The subject heading is: “Read only if you teach Year 11” and my heart sinks a little.

As I open the main body of the email and read the opening sentence - “Apologies for the late notice, but…” - my heart drops even further.

It reads: “The following students will be leaving at lunchtime today to take part in the following theatre trip/sports fixture/visit to an art exhibition/search for some very important rocks for their geography coursework (delete as necessary).”

Cue huge explosions of anger from the rest of my department: “This is ridiculous”; “I haven’t seen Craig Evans in my lesson for two weeks now”; “How can we be expected to get the syllabus covered in time?”; “We are a core subject so our lessons should be protected...”

No time for trips

Trips are a controversial topic in schools. Arguably, there is nothing more divisive between departments than the constant battle for students’ time, so decisions about when and how trips are conducted can cause a huge rift across staffing bodies. With the higher content demands of the new curriculum, things have worsened: there is no good time to take students out of lessons.

But I am not here to advocate the end of trips: I believe they are a really important part of academic enrichment. What I want to argue instead is that we need to change the way we organise them. I think two strategies may work.

1. Create a trips week

Many schools conduct a successful activities’ week at the end of the summer term when, let’s face it, everyone’s ability to concentrate has gone out the window. By scheduling all students and staff to be off timetable at the same time, one ensures that:

a) all students access some kind of non-academic enrichment;

b) the arguments about students being taken out of lessons are, in theory, reduced.

So why save this for the end of the year? The last week of the autumn and Easter terms can suffer from fatigue and lack of motivation, as well as disruption from festivals, events and the like.

So, instead of us going through the rigmarole of pretending to teach to the bitter end, why not have an activities’ week every term?

2. Pay teachers for their time

A straw poll of colleagues in a variety of schools suggests that more and more schools are adopting a “no trips in the school day” policy. This is due to the financial implications of paying for expensive supply teachers to cover the students who are not on the trip. Scheduling all trips for the last week of term would, in theory, lessen this financial burden.

However, if trips do have to be reserved for outside school hours, then teachers should be rewarded financially for their time. When you have already been in school since 7.30am, conducting an out-of-hours theatre trip is no small ask for staff, no matter how committed you are to your subject.

When one factors in one’s own childcare costs, transport home and maybe a parents’ evening later in the week, the incentive to organise trips becomes less and less. If you were getting paid extra for your overtime, you might feel more inclined to volunteer. Ditto giving up your well-deserved holidays. No teacher is in this profession for the money, so we wouldn’t require much extra pay. Thus, I don’t believe it would be a huge chunk out of a school budget to go down this route.

Will it work?

Clearly, the second approach is tricky in a time of tight school budgets, but it would reduce supply costs of replacing staff out in the school day. It should be cost neutral, or more likely a saving.

As for the first approach, clearly we can’t account for the scheduling of all external organisations with whom we liaise. However, over time, if education departments were briefed with enough notice, I am sure that they would be amenable to working towards meeting a school’s schedule.

I can also hear alarm bells ringing about how difficult this is all going to be to facilitate. However, schools might feel that it is a good use of their resources to employ a designated non-teaching trips leader to run the entire process. Thus, the week could be co-ordinated by one person.

I think either of these options will work, but I am keen to hear any other ideas of solving this issue. We need to find a balance that rewards teachers and doesn’t impact pupils’ academic studies too greatly, but that lets these really important trips continue.

Katherine Burrows is an English teacher at Abingdon School in Oxfordshire

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters