- Home

- Sorry shouldn’t be the hardest word when crisis hits

Sorry shouldn’t be the hardest word when crisis hits

With apologies to Sir Elton John, “sorry” seems to be the word of the moment - whether because of its use or lack thereof.

There are numerous recent examples of leaders at all levels saying sorry. Think of the recent apologies by education secretary John Swinney and first minster Nicola Sturgeon about the 2020 “exam” results, or the University of Glasgow saying sorry in 2019 for its historic links to slavery. Going a lot further back, a classic example of the genre was the remarkable apology elicited from disgraced US president Richard Nixon by David Frost.

An authentic apology is offered without conditions or minimising what hurt has been done. It’s remorseful and contains a promise of no further such hurt. While there are countless examples of these during the pandemic, from leaders in various parts of the world, not all those in positions of power or authority are able to bring themselves to offer this authenticity.

The 2020 Scottish Qualification Authority (SQA) exam fiasco offers examples of “conditional” apology. At the Scottish Parliament’s Education and Skills Committee in August, CEO Fiona Robertson told us that she “regrets” how young people felt over their downgraded exam results - yet she continued to contend that the moderation system used by SQA had been “fair”.

Background: SQA refuses to apologise for results debacle

To apologise or not to apologise: How the SQA defended the results fiasco

SQA results debacle: Sturgeon says ‘sorry’

Priestley review of SQA results fiasco: 17 key findings

Sorry (not sorry): Overreliance on half-hearted apologies from pupils gets in the way of real solutions

In the Priestley review of the whole affair, there are a few further examples of what could be described as a conditional apology from the national examination agency. In Tes Scotland last month, Henry Hepburn’s account of the Priestley review cited various non-apologies from the SQA about its role in the hurt, upset and anger the approach to the 2020 exam processes caused.

The Priestly review noted: “The SQA has stated to us that there is no regret in respect of the moderation approach used this year (in terms of its technical application), but that the regret lies in the fact that the [post-certification review] process was not allowed to run its course, as this component was designed to deal with the sorts of problematic results that generated such an intense political and media focus after results day on 4 August.”

The SQA, it seems, believes the issue was one of message and communication rather than equity, fairness and, of course, harm; it has expressed no regrets in respect of the approaches used.

This short article isn’t really about the exam issues of 2020, but about the importance of apologising. As a woman in the workplace, I have been on the receiving end of the “I’m sorry that you felt that way” type of apology. I’ve witnessed a teacher apologise to a pupil in a similar manner: “I’m sorry if you...” These apologies are poor, conditional and an attempt to shift the blame. They are not authentic: to be authentic, the person giving the apology has to own the error, the misdemeanour and the behaviour.

We all make genuine mistakes. Should school leaders apologise to teachers after making a mistake? Should teachers apologise to children and young people when they make a mistake? Of course -we all should.

If education internationally is to be built on the Unesco “four pillars” (learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be), then we as teachers need to model the behaviour we want our children and young people to develop. In Scotland, if we are to deliver on the values-based education system we espouse then we need to model these values of justice, wisdom, compassion and integrity.

If we do not own our mistakes or errors, what lessons are we teaching our colleagues and children? That being in a position of power or authority means you never have to say sorry?

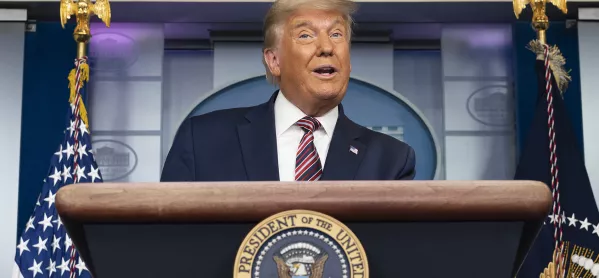

Maybe this from Maya Angelou - which feels particularly apt given current events on the other side of the Atlantic - is worth including in your school-values statement: “Apologising does not always mean that you’re wrong and the other person is right. It just means that you value your relationship more than your ego.”

If everyone said knew how to say sorry properly, in education and beyond, the world would be in a far better place.

Isabelle Boyd is an education consultant who formerly worked as a secondary headteacher and local authority assistant chief executive in Scotland. She tweets @isaboyd

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters