As a sociologist, my first reaction to the news that the biggest exam board has dropped the theme of suicide from its A-level syllabus was one of disbelief. In its wisdom, AQA has decided that students cannot be expected to discuss a topic as distressing and risky as suicide. Consequently, the study of one of sociology’s main foundational texts, Emile Durkheim’s Suicide, will have to go too.

It is important to recall that Durkheim’s classic is not just another book. This study offered a pioneering example of what the discipline of sociology could accomplish through the use of a rigorous methodology and statistics. For almost a century, Suicide has been used as the text through which sociological concepts and methods were introduced to students. Getting rid of Durkheim is like dropping the theory of relativity from the study of physics.

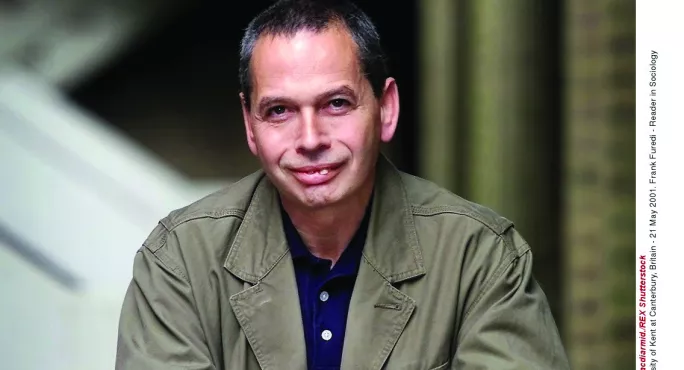

The decision to impoverish the sociology A-level curriculum was justified by Rupert Sheard, AQA qualifications manager, on the grounds that his organisation has a “duty of care to all those students taking our courses to make sure the content isn’t going to cause them undue distress”. The argument that this dry historical review of 19th-century suicide statistics is going to constitute a source of distress is bizarre. Just because it contains the word “suicide” in its title does not mean that by any standards of sensitivity this is a disturbing or traumatising book.

However, even if some students found Suicide upsetting, is that an argument for dropping this classic text? As a discipline, sociology is in the business of questioning comfortable assumptions and, in so doing, it frequently draws attention to the dark and destructive passions that prevail in human society. Sociology at its best disturbs and forces its students to engage with some very uncomfortable realities. If, indeed, AQA wants to turn education into a distress-free zone, it might as well stop offering sociology A-level altogether.

Unfortunately, the real problem is not the silly decision taken by AQA regarding a relatively dry and non-emotional text. The true menace haunting education is the powerful trend towards the medicalisation of the curriculum and the classroom. The most grotesque form assumed by this trend is the introduction of so-called “trigger warnings” in higher education. In some American universities, novels and even poems come with a health warning, indicating that they contain scenes of domestic violence, sexism, racism and a variety of other pathologies that may set off flashbacks for readers.

The premise of the trigger-warning crusade is that students cannot be trusted to engage with uncomfortable subjects. Nor can they be allowed to judge for themselves how to interpret difficult and challenging experiences and practices. The attempt to impose a moral quarantine around uncomfortable and dark dimensions of human experience serves to diminish the experience of education.

Teachers, who take the teaching of their disciplines seriously and who regard their pupils as students rather than as patients, must protest against the violation of the sociology curriculum. How long before other subjects are forced to alter their curriculum in order to make it patient friendly? If Durkheim can be excised from sociology, how long before the Bible is dropped from the religious studies curriculum? With its discussion of child abuse and child murder, rape, mass slaughter, torture and violence, this is clearly not a text for the faint-hearted. Incidentally, it also contains more than its fair share of graphic suicides.

And will Shakespeare be the next target of the “let’s protect the children from bad stuff” brigade? After all, Jewish students might be distressed by the anti-semitic lines in The Merchant of Venice. And will the study of slavery and the Holocaust be dropped from the history curriculum because the violence associated with these tragedies could upset some in the classroom?

Whether the content of a particular text causes distress to students cannot be determined according to a pre-existing formula. Individual memory and experience reacts to the content of a text in the most unpredictable manner. Insulating students from unpleasant reminders of their predicaments will not necessarily help them to deal with upsetting experiences in the different contexts within which they emerge.

The way to deal with students’ feelings is through sensitive teaching of difficult topics. The alternative is to avoid difficult discussions altogether, which is not what education should be about.