- Home

- Teachers will always work overtime. Now pay them more

Teachers will always work overtime. Now pay them more

Guy Doza wrote eloquently last week about teachers working overtime. It’s nothing to be proud of, he tells teachers, and it leads to a “culture of unmanageable expectations”.

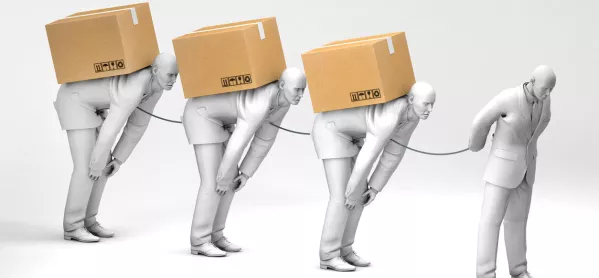

Teachers are overworked, he says, and underpaid (both true). They’re expected to work long hours, to such an extent that failure to “go above and beyond” brings their work ethic into question.

But he’s critical of those who succumb to the pressure or willingly give up time to market their school through open evenings, or catch up on work at weekends, because of the impact it has on the people around them.

Soul-searching

Such pieces inevitably stimulate some soul-searching. Did I ask too much of my colleagues in 28 years of headship? I ran highly pupil-centred schools, with busy extracurricular programmes and very dedicated teachers (I can sense Mr Doza grinding his teeth), who worked hard. I don’t think I demanded too much of them - though, for an objective view, you’d have to ask them.

Did I say objective? That’s tricky. Mr Doza deplores teachers doing anything outside contracted hours. But what constitutes a reasonable, even a contractual, teacher workload?

When I was a young teacher (I started in 1978), teacher workload was an ill-defined thing, though teacher unions repeatedly initiated work-to-rule campaigns for better pay. (We really were badly paid back then.)

In the late 1980s, Kenneth (now Lord) Baker decided to end the argument, asserting that teachers must work 1,265 hours in a year. This created immense ill-feeling. I knew fantastic teachers, who had long exceeded that figure, who responded by ceasing to run school sports teams, choirs or play productions. “If that’s what he thinks of us,” one told me, “he can stuff it.”

Removing professional trust

It was the first miserable - but significant - step in the Thatcher and Major governments’ process of removing professional trust from public services and introducing micromanagement, enforced by an oppressive accountability regime.

Thirty years on and, regardless of who’s in power, it seems impossible to row back from it. Actually, I’m amazed that any goodwill remains in the profession. Astonishingly, it does, even if it attracts Mr Doza’s ire.

He insists a coffee-shop barista wouldn’t say, “I don’t mind staying late to share the drink that I love.” But what about a crisis? Wouldn’t a committed employee stay on when the espresso machine blows up five minutes before the end of their shift? Maybe the employer would find some overtime pay, maybe not. But isn’t staying to help the natural, human thing to do, expressing both loyalty to customers and pride in the job?

That’s a trivial example. Commentators on the Tes webpage cited health workers who go the extra mile to save lives. The remarkable numbers of off-duty doctors and nurses who reported unbidden to London hospitals after the Westminster and London Bridge terrorist attacks didn’t ask about overtime before getting down to work.

Similarly, I suspect safety and repair workers up and down the country turn out to keep road and rail networks open when emergencies strike. And they keep at it till it’s done because, well, it matters.

Openness, flexibility and humanity

As a head, I tried to protect my staff from outside pressures. I sought change and improvement, naturally, but on a basis of reasonableness, openness, flexibility and humanity. (Nor did I expect teachers to read or send evening or weekend emails.) True, the greater freedoms and resources of the independent sector made this easier. But don’t underestimate how demanding private-school parents can be.

I cling stubbornly to a vision of teaching as a caring and people-focused profession: one which accepts that those whom it serves are unpredictable and demanding and will, at times, desperately need it go the extra mile.

But, if such generous professionalism is desirable, as I passionately believe it is, government must in return treat teachers as professionals: pay them better; stop micromanaging, controlling, exploiting, bullying and overworking them; give them time and trust; genuinely value them.

Until it does that, ministers’ claims to be “tackling workload” will remain mere empty rhetoric.

Dr Bernard Trafford is a writer, educationalist, musician and former independent school headteacher. He tweets @bernardtrafford

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters