- Home

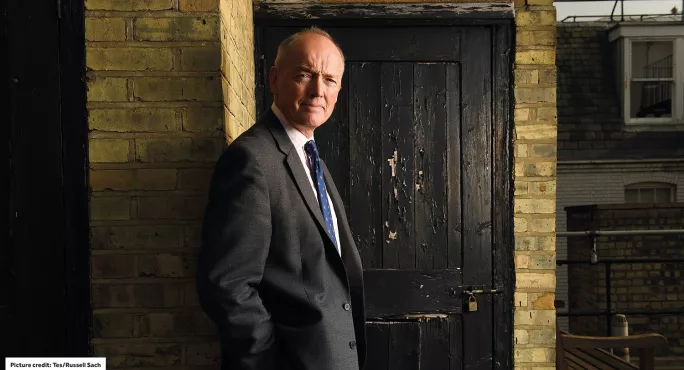

- Tes talks to...Mark Castle

Tes talks to...Mark Castle

Mark Castle is describing, in stark terms, the devastating impact that crime against a child can have on that young person’s chances of future success: “I spoke to a victim of historic child sexual abuse recently and he said, ‘The thing that people don’t understand is that, because the abuse occurred at a critical point in my education, my whole life was altered as a result.’”

Castle is the chief executive of the charity Victim Support and it is testimonies such as this that strengthen his belief in just how important teachers can be in helping young people to cope with being the victim of a crime.

Castle knows only too well the importance of supporting people through times of acute distress. Towards the end of a 30-year career in the armed forces, he was involved in the reconstruction of Iraq, working on the ground to develop the security infrastructure that would allow local communities to rebuild. “The fundamental thing, from what I saw in Iraq, is that if you don’t look after people who have been victims of crime, you can’t get the healthy society that we need,” he says, pointedly.

A surprisingly high number of children are victims of crime in the UK. The latest Crime Survey for England and Wales estimates that around 11 in 100 children aged 10 to 15 were victims of at least one crime in the previous 12 months. And although the total number of crimes experienced by children fell by 17 per cent on the previous year - consistent with a downward trajectory over the past eight years - the problem remains serious and pervasive.

Crimes include physical and emotional bullying in schools, as well as online activity resulting in bullying and sexual exploitation - a relatively new and growing problem. Violent crime and theft feature prominently in the list of offences committed against young people, too. Victim Support aims to assist victims across the full range of crimes although, with young people, it is not just about direct interactions between the charity and the young person but also facilitating better support from schools.

Get the basics right

Castle notes that there are currently significant variations in the ability of schools to support child victims, much of which comes down to training. Often, teachers are best placed not only to spot victims of crime but they are also the most likely people that a young person will turn to if they are a victim, so a lack of training can be a problem, Castle says.

Teachers do have training around safeguarding but Castle believes this often needs boosting. Victim Support provides a huge range of resources and training courses to help, but he says a lot of the impact a teacher can have is in getting the basics right. “What teachers have got to look out for is someone obviously emotionally different from the norm, for example they are quick to become angry,” he says. “Another symptom is that people have trouble sleeping, so if someone is obviously much more fatigued than they would normally be, there might be other things that are going on.

“If they quite clearly look as though they have lost their appetite or are feeling scared or are suffering panic attacks, all of those things give an indication that something is not normal and should be triggering the teachers to be thinking about intervening in some way.”

Teachers may assume that if there was something to worry about, someone closer to the child may have spotted it. But Castle says teachers are in daily contact with their students and, as such, are well placed to know what is normal for that child and to pick up on any changes in behaviour at the earliest opportunity and intervene before the problem escalates.

It’s also important that teachers realise it is often them that a student chooses for support, he adds. He explains that children are more likely to feel comfortable talking openly in a familiar environment such as school rather than a place where they feel as if they are being singled out. “A child going to a police station is very different from a child speaking to a teacher,” he says.

Once a teacher has identified that there is an issue, Castle’s first piece of advice is for them to find a good opportunity to talk to the child, at a time and location that doesn’t attract attention, especially where bullying is the issue. Other tips include asking open-ended questions, “because by doing that, you’re not being subjective in any way; what you’re trying to do is to get them to give you the information”.

Take each case as it comes

With younger children in particular, asking them to express their feelings through drawing rather than vocally can often be a better way of encouraging them to open up.

If a child does disclose something, Castle stresses that it is often the case that they won’t necessarily recognise they are a victim of a crime. This may be because they do not understand that what has occurred is criminal activity. So there is a guidance, as well as a support role, to be played in schools.

Most critically, any interventions must recognise that each individual circumstance is different. Dealing with one victim of crime does not mean that you can take that experience and apply it directly to a second victim - even when the offence is similar.

“If you’ve been a victim of violence, been stabbed, or a victim of terrorist activity, the pathway and the starting point are slightly different to a victim who’s maybe been the victim of chronic crime, for example groomed as the victim of sexual abuse,” says Castle.

It’s important, too, for teachers to give a sense that they are not judging the child, especially when the perpetrator is known to the victim, as is often the case in the school environment, and to regularly go back and check that the situation is improving.

In the most serious cases, when the teacher feels the need to escalate the issue, they should first and foremost refer to the school’s safeguarding policy. “Every school will have one and they should conform to that because it is then recorded,” says Castle.

One particularly delicate area is where the perpetrator is a fellow student. In such circumstances, Castle says that, where appropriate, the school should try to work with that individual, too, since although they may be a perpetrator now, they have most likely become a perpetrator because they’ve been a victim themselves.

“Getting involved with the child who’s the perpetrator may well be the best way to stop it because they may think that whatever they’ve done is normal behaviour,” says Castle. “Making them aware that it’s criminal behaviour may be the catalyst for them to stop.

“This is not easy, but if we’re going to reach a point where the victimisation is going to stop, the perpetrator has to be engaged with,” he says.

A lot of this may seem like common sense, but Victim Support clearly believes that teachers need more support. Ultimately, as with all crime, prevention is better than cure. But when help is needed, teachers are as well placed as anyone to ensure that a young person’s life isn’t defined by a traumatic event and Castle wants to make sure we empower those teachers to do all they can to help.

Nick Hughes is a freelance writer

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters