- Home

- #ToYouFromTes: The myth of inclusion

#ToYouFromTes: The myth of inclusion

Meet Reece. We join him in Year 5. He has a global learning delay and his expressive and receptive language skills are underdeveloped for his age. Each day, Mandy, a teaching assistant (TA), takes Reece out of the classroom with Sula and Nathan to work on their social language. They practise important skills such as greeting people, talking in turns and not interrupting.

But here’s the thing: Sula and Nathan have communication difficulties, too. And while Mandy does a great job of trying to initiate and sustain conversation among the three children, progress is slow.

Fast forward to Year 9. Reece is sat with Jacqui, another TA, at his designated table in bottom-set science. His teacher is explaining that Mars’s orbit of the Sun is almost twice as long as Earth’s orbit.

It’s not dissimilar to the teachers’ orbit of the classroom. Because Jacqui is on hand to help, the teacher checks in with Reece about half as often as he does with other pupils.

And these are just snapshots of Reece’s time in school. If you were to sit with him every day, you would witness a journey through the education system that is pockmarked with separation, segregation and unintentional outcomes.

Reece’s story is a composite one. He is an example of what it is like to be a child with SEND in the school system. Findings from longitudinal research that I led along my UCL Institute of Education colleague, Professor Peter Blatchford, suggest that Reece’s experience is a typical one.

We conducted two studies: one in 2011-12, the other in 2015-16. The most recent is the SEN in Secondary Education study, which involved 60 pupils with statements of special needs or education, health and care plans (EHCPs) in Year 9 across England. This project replicated our earlier Making a Statement study, in which we tracked 48 pupils when they were in Year 5. Thirty of the students involved appear in both studies (see box, page 45).

It is, to our knowledge, the largest classroom observation study ever conducted in the UK on pupils with SEND. Our researchers visited 88 schools, shadowing pupils for up to five days. They also collected comparison data on 260 average-attaining pupils. In all, we spent 1,340 hours observing pupils and carried out 490 interviews with staff, parents and pupils.

The findings raise important questions about how schools “do” inclusion. The main one being: do we actually do it at all?

Separation and setting

We found that pupils with EHCPs in primary schools spent the equivalent of more than a day a week away from the mainstream class - effectively separated from the teacher, the curriculum and their peers. When they worked in groups, it was mostly with other low-attainers and those with SEND.

What we found in secondary schools was very close to a form of “streaming”. Seventy-five per cent of lessons in English Baccalaureate subjects for pupils with and without SEND were taught in attainment groups. Pupils with EHCPs were taught mainly in what they themselves referred to as “bottom sets”, with at least one TA working alongside the teacher.

Compared with average-attainers, pupils with EHCPs spent more time in smaller classes. They were taught in classes of 16 or fewer pupils in 54 per cent of instances (compared to 11 per cent for average-attainers), and in classes of 21 or more in 26 per cent of instances (69 per cent for average-attainers).

School leaders tend to justify “ability” grouping across year groups and within classes as part of a wider teaching strategy. We were struck by how this was described as a main form of differentiation. In some cases, grouping appeared to eliminate the need for providing different tasks for pupils with EHCPs.

This is problematic. Research has consistently found that while “high-ability” pupils benefit from the positive affirmations of being top of the class, there is a corrosive effect for those in “bottom sets” in terms of their confidence, self-concept and how they view their place in school. As one Year 9 we interviewed (see box, below) put it: “I don’t like telling my friends I’m in the bottom set, because I think they would find me different.”

Becky Francis, director of the IoE, is leading an Education Endowment Foundation-funded trial into ability grouping. She says: “Research shows that pupils in these low-attainment groups make less progress than their peers in higher-attainment groups.

“The present project, Best Practice in Grouping Students, is seeking to address the practices associated with low-attainment groups that research has identified as contributing to these poorer outcomes. The approach includes ensuring that these groups have equal access to experienced, subject-expert teachers, high expectations and a rich curriculum.”

The potential self-fulfilling prophecies for those placed in low-attainment groups and labelled “low ability” are harder to address, she adds. “Likewise, while all educators believe we have high expectations of our students, there is a need to think about how this actually translates into practice.”

In short, the way we separate out children with SEND into low-attainment groups in secondary, and take children away from the teacher, curriculum and peers in primary, is highly problematic and detrimental to their individuals concerned.

Time with teachers

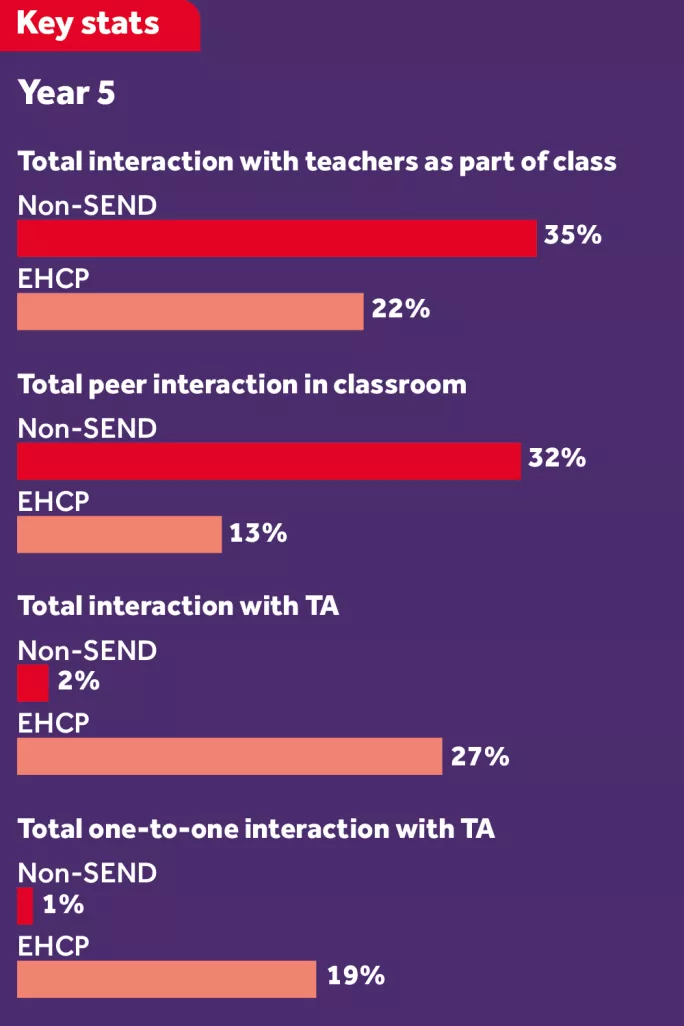

In Year 5, we found interactions with teachers comprised 35 per cent of average-attainers’ overall classroom experience; for pupils with EHCPs, it was 22 per cent.

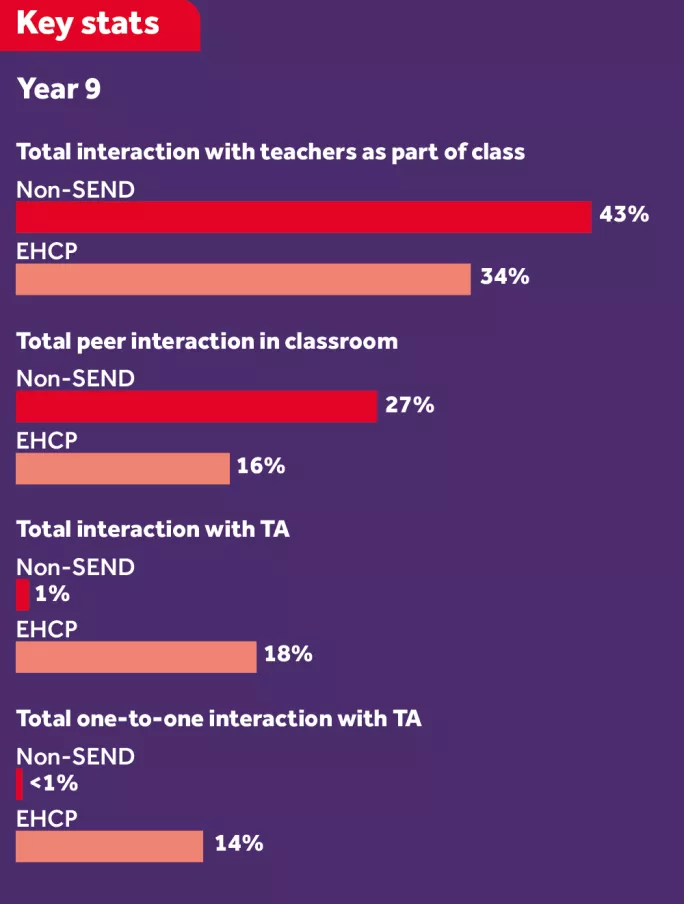

In secondary settings (where pupils weren’t withdrawn from the classroom as much), it’s less marked (43 per cent vs 34 per cent).

These results matter, because it shows that the pupils who need the most time with the teacher get the least interaction.

Peer interaction

We found that compared to those without SEND, pupils with EHCPs have strikingly fewer opportunities to interact with their classmates. For average-attainers in primary settings, 32 per cent of all classroom interactions were with peers; for those with EHCPs, it was 13 per cent.

In secondary schools, interaction among average-attaining pupils accounted for 27 per cent of classroom interactions; for those with EHCPs, it was 16 per cent.

To put it more bluntly: pupils with SEND mix and interact mostly with one another. That has numerous downsides.

For example, as our composite scenario with Reece illustrates, pupils who need to practise and develop their communication skills do so together, rather than with peers who can model good speaking.

And pupils who learn together in particular attainment bands tend to form friendships together. Those with SEND can be a vulnerable group, less at ease with the bustle of a crowded playground. The learning support department often doubles up as a place for them to spend break and lunchtimes. While there is nothing intrinsically harmful about this, it does lead to these pupils being isolated in social as well as learning contexts.

The presence of TAs

The explanation for why pupils with EHCPs have fewer interactions with teachers and peers is writ large in our data on interactions with teaching assistants. For typically-developing pupils, TAs make up 1 per cent and 2 per cent of all interactions they have with peers and adults in secondary and primary settings respectively. Yet for pupils with EHCPs, talk with TAs makes up 27 per cent of all interactions in primary school, and 18 per cent in secondary school.

The bulk of these pupil-TA interactions occur on a one-to-one basis. On the face of it, this is common-sense: if you struggle with learning, more individual attention from a TA looks like an appropriate makeweight for less interaction with teachers and classmates. Teachers can then focus on the rest of the class.

Yet research tells us there are three distinct problems with this set-up.

Firstly, it leads to subtle forms of separation, such as “stereo-teaching”. This is where a TA will repeat verbatim what the teacher says as she delivers her whole class input. For the teacher, it’s like experiencing a satellite delay, as you hear your words echo in a corner of the room. But more importantly, it interrupts the pupil’s experience of your teaching, as they have to toggle between talk from two adults: not helpful if one of your primary difficulties is related to attention.

Secondly, it fosters dependency and learned helplessness. At worst, pupils “outsource” their learning to a well-meaning TA, who completes tasks for them.

Thirdly, the more TA support pupils with SEND receive, the less well they perform academically, compared to their less-supported peers (bit.ly/DISSproj).

This lack of progress isn’t due to pupils’ underlying SEND or prior attainment, nor because TAs aren’t doing a good enough job. What it is, however, is an indication that the model of inclusion we have drifted towards over the last 25 years stands as a proxy for unresolved questions about how pupils with SEND are taught in mainstream settings.

Conclusions

The picture our research paints is best understood in terms of less than effective leadership for SEND. I’ve seen what great school leaders can do to improve the impact of TAs (bit.ly/TA4tips) - and, conversely, the confusion and inconsistency that results when important decisions about TAs’ role and purpose are left unresolved.

But improving how we include and educate pupils with EHCPs in schools cannot and will not be resolved merely by making better use of classroom TAs.

The quality of SEND coverage in initial teaching training must be addressed. Tensions and flaws in the SEND assessment system - identified by its original architect, Baroness Mary Warnock (bit.ly/SENDsystem) - must be ironed out. In particular, we need to emphasise that what matters most is the quality of support (what pedagogical inputs are required, who delivers it, and how), not the quantity of support, which is too often couched in the currency of TA hours.

Schools are the best engines for change. We urgently need headteachers to take responsibility and apply the same tenacity to SEND that they devote to other areas of school improvement. In short: it’s time to make SEND a priority.

We need to take decisive action to make our schools more inclusive and productive environments for our most vulnerable children and young people.

So, what can leaders do?

First, review the institutional arrangements and classroom practices that get in the way of pupils with SEND being on the receiving end of high-quality teaching. Inclusive practice isn’t just where pupils are “in” the class; they need to be “of” the class - actively engaged in learning.

Second, improve the social mix. Schools could take the bold step of introducing mixed attainment grouping for at least some subjects, if this is not something that they do already.

Compared with “ability” grouping, mixed attainment teaching has greater potential to improve outcomes for all pupils. At the least, teachers should ensure pupils with SEND aren’t routinely put together for paired or group work, and create opportunities for them to work with, learn from and interact with others.

Third, school leaders should rigorously define the role and contribution of TAs as an effective part of - not the sole solution to - SEND provision. A good place to start is the free guidance that we have developed with the Education Endowment Foundation (bit.ly/EEFTA).

Finally, schools should institutionalise leadership for SEND in their career progression systems: no-one should move up the leadership ladder without evidencing how great they are at improving outcomes for pupils with SEND.

Will any of this happen? I can only hope so. With the issue of selection continuing to rear its head - most recently in the Conservative manifesto - children and young people with SEND and their families need strong and committed leadership now more than ever.

We need to stand up for these young people and stop this inclusion illusion we are currently all buying into, which continues to undermine the life chances of this already vulnerable group.

Rob Webster is a researcher at the Centre for Inclusive Education, UCL Institute of Education. He tweets @maximisingTAs. The SEN in Secondary Education (SENSE) study was funded by the Nuffield Foundation. Download the SENSE study Final Report from bit.ly/SENSEstudy

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters