I never thought I’d find myself feeling sorry for universities. For many years of headship, I was actively involved in helping students into higher education: and, as often as not, was driven to screaming point. That’s just the nature of being part of the assembly line that seeks to send many 18-year-olds on to the courses and institutions that suit their personalities, talents and aspirations: like it or not, that’s a major (but far from the only) part of secondary schools’ work.

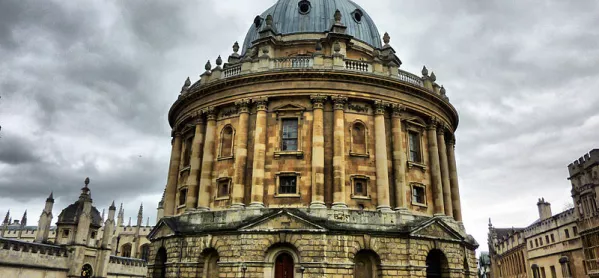

So, over the years, I may have cursed universities at times: but, now that they’re on the receiving end of criticism from all quarters, they have my sympathy. They’ve been slated for the surprisingly large number of unconditional offers made to students: at the same time, Oxford (among others) is in the firing line for the lack of diversity of its entry.

And on Thursday The Times reported, “Fee-hungry universities lower bar to entry”. The thrust of this story is that many candidates are now scraping into university with no more than three D grades: apparently, 80 per cent of those relatively low achievers won places.

Of course, the media - or, at least, the subs who pen the headlines - frequently adopt the tone that the world is going to hell in a handcart. Since the current state of Brexit suggests we’re indeed heading in that direction, who can blame that sense of doom from permeating education stories too?

Nonetheless, it’s worth exploring the implication that there’s something wrong with DDD candidates going to university. Wasn’t it once an ambition that 50 per cent of school-leavers were doing so? Or is that just another Blair mantra that we now reject?

The Times piece was balanced, citing students who achieve disappointing A-levels - usually because non-school elements conspire against them - but succeed in their degree course.

Isn’t one of the purposes of higher education to allow young adults to continue in education and equip themselves academically and intellectually for the rest of their lives? For many years there have (rightly) been alternative access routes for those who don’t get it right aged 18. One is via Further Education, now battered by government and insanely starved of funds.

When it comes to unconditional offers, I regret to disagree with my many erstwhile fellow heads who criticise their growth. The argument is that, having received them, young people take their foot off the accelerator (as I would have done at that age) and saddle themselves with poor grades that, it’s suggested, mar their CV forever.

I’m sorry to irritate those colleagues just before Christmas, but we can’t have it both ways. We’ve spent the last few years bewailing the pressure put on applicants by holding high university offers. Indeed, if we’re honest, those offers were frequently beyond their reach: but schools have known that most universities (not the top selectors, perhaps, but most) nowadays allow latitude for candidates falling short.

So we rightly deplore that particular pressure - but opponents of unconditional offers perversely insist on allow that pressure to build through to the summer of Year 13. As for criticisms of universities “lowering the bar”, it’s surely contradictory to promote life-long learning through HE and beyond and then complain if universities, driven by government policy to pursue student numbers, are prepared to take a punt on those who haven’t done so well at age 18.

There’s an answer to this contradiction. Government, universities and schools should get round the table and plan a workable strategy for students to apply to university with their A levels under their belt. But PQA (Post-Qualification Application) would demand wholesale structural change, and the collective will to embrace it has been lacking for forty years, to my knowledge.

Besides, such change would require consensus which, in the current political climate, isn’t at all the modus operandi: on that, at least, we can all agree.

Dr Bernard Trafford is a writer, educationalist, musician and former independent school headteacher. He tweets at @bernardtrafford