- Home

- ‘We may have travelled a long way from the inkwells of the Victorian classroom, but we are still some distance from a…

‘We may have travelled a long way from the inkwells of the Victorian classroom, but we are still some distance from a curriculum that encourages critical thinking’

“It is doubtless desirable that the poor should be generally instructed in reading, if it were only for the best of purposes - that they may read the Scriptures. As to writing and arithmetic, it may be apprehended that such a degree of knowledge would produce in them a disrelish for the laborious occupations of life.”

This is a quote not from a Dickens novel, but from a justice of the peace in 1807. At the beginning of the 19th century, educating the working classes was seen by many as not only unnecessary, but dangerous: teach a child to think and you might also teach them to become discontented with their lot.

As the century progressed, campaigners for mass education established various schools to offer some basic teaching: Sunday schools taught the poor to read the Bible (but not writing, arithmetic or any of the “more dangerous subjects”); schools of industry were set up to provide manual training; and ragged schools were by 1861 teaching more than 40,000 of the most deprived children in London. In that year, an estimated 2.5 million children out of 2.75 million received some form of education, with the majority leaving school before they turned 11.

‘Stick to facts, sir’

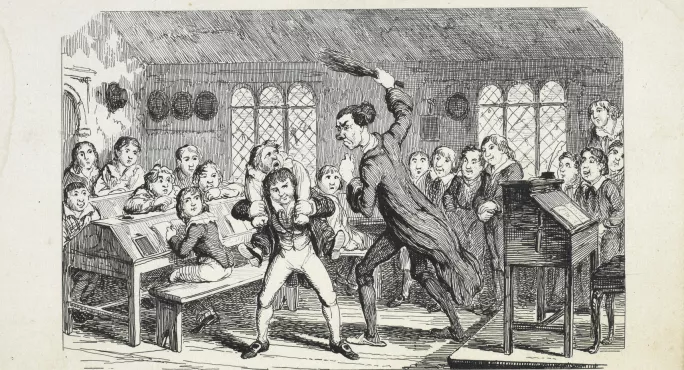

However, the schooling - although better than nothing - was almost exclusively learning by rote, with poorly paid teachers reading facts and scripture to large roomfuls of children. There was no space in such a regime for critical thinking. Independent thinking was considered dangerous.

The upper classes did not, of course, send their sons to any of these schools. They moved from private preparatory schools to the great English public schools, Eton, Westminster, Winchester, Harrow - establishments that inculcated knowledge of Latin and Greek, the virtues of sport, a sense of hierarchy and a strong sense of duty.

New boarding schools (Marlborough, Radley, Malvern) were springing up to accommodate the sons of the growing middle classes. In those schools, too, the emphasis was on facts and assessment; on recitation and repetition. Charles Dickens’ most memorable criticism of that system was Thomas Gradgrind in Hard Times: “Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else… Stick to Facts, sir!”

Damaging the ovaries

Things were rather different for the daughters, whose minds were inferior and for whom too much education would, it was feared, be harmful. Some doctors even suggested that if the “stream of vital and constructive force” was turned to the brain, it could damage the female ovaries.

In the main, girls were taught at home by ill-trained governesses who provided a mishmash of religious instruction, reading, writing, needlework and perhaps French. Girls also worked on their “accomplishments”: drawing, singing, piano playing, flower arranging. The aim of all this was not to enrich the mind - it was to make the girls marriageable. This is why, in my novel The Unseeing, fallen woman Sarah Gale says that her education has prepared her for nothing save for life as a seamstress and a prostitute.

A movement for better education for girls and women began in 1843 with the foundation of the Governesses’ Benevolent Institution, which aimed to provide proper qualifications for governesses. This led to the foundation of Queen’s College in Harley Street in 1848, which adopted an academic curriculum. A similar institution, Bedford College, was opened in 1849.

Pupils from these colleges influenced many areas of feminist life in the 1860s and 1870s, including early suffrage and married women’s property movements. Former pupils included Sophia Jex-Blake, one of the first female doctors in the UK, and Octavia Hill, the social-work pioneer. But perhaps the most important were Dorothea Beale, first principal of Cheltenham Ladies’ College, and her friend Frances Mary Buss, who founded North London Collegiate School. Both became key players in the campaign for girls’ education, countering the belief that educating women was dangerous and unfeminine. Both gave evidence at the Schools Inquiry Commission of 1864-67 after feminists insisted on the commission widening its scope to examine girls’ education. Asked by a commissioner whether there was not a “distinction between the mental power of girls and boys”, Miss Buss responded tartly: “I am sure that the girls can learn anything they are taught in an interesting manner, and for which they have some motive for work.”

But people had been right to fear that education for women would lead to problems: calls for votes for women grew ever louder, leading in 1897 to the founding of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Queen Victoria was furious: she saw absolutely no reason why women should want to vote.

Speculate about the possible

I know many teachers now have concerns that we are returning to a Victorian-style methodology so focused on facts and tests that there is little room in the classroom for creative thought and critical thinking. They are frustrated by a curriculum so geared towards the end result - to grade rather than the content - that they do not have space to encourage children to create and to think for themselves.

Research released by Oxford University Press in June revealed that 56 per cent of teachers are concerned about children missing out on the chance to be inspired by reading in the classroom. In May, many parents in England took their children out of school in protest at the “19th-century-style testing” imposed by the new national curriculum for key stages 1 and 2. Reading through the key stage 2 English paper with my niece, I was reminded of Dr Blimber’s academy in Dickens’ Dombey and Son. There the children “knew no rest from the pursuit of strong-hearted verbs, savage noun-substantives, inflexible syntactic passages, and ghosts of exercises that appeared to them in their dreams”. That, of course, is unsurprising, given that this curriculum is the legacy of Michael Gove and his obsession with rote learning, memorisation and facts. Blimber and Gradgrind would have approved.

We may have travelled a long way from the inkwells and slates of the Victorian classroom, but we are still some distance from a curriculum that is creative, inclusive and which encourages critical thinking. We need to ensure that children’s imagination is nurtured, giving them the capacity to speculate about the possible.

If the chaos of this past week has shown us anything, it is that children must be taught not to follow blindly - not to accept unquestioningly the facts they are told - but to think for themselves.

Anna Mazzola’s debut novel, The Unseeing, set in London in 1837, is published on 14 July by Tinder Press (Headline). She tweets as @Anna_Mazz

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters