- Home

- What your handbag can teach you about memory

What your handbag can teach you about memory

“I’m not going in there,” my husband whimpered. “You can’t make me.”

I’d only asked him to try to find my keys in my handbag - my very messy, full-to-bursting, portable filing cabinet of a handbag.

But he had a point: it was impossible to find anything in there. There was simply too much stuff, badly organised, to make finding anything straightforward.

My mother’s handbag, on the other hand, was a model of organisation. She only ever bought bags with compartments and pockets, and everything was filed away in its proper place. Finding her keys was a breeze.

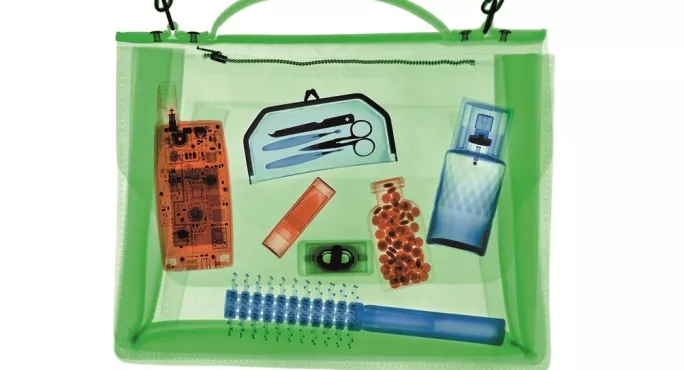

Long-term memory is a bit like a handbag. We can store a vast array of memories in it, but how well we are able to find them when we need them depends on how organised it is.

And organising memories is where retrieval practice comes in. You have probably heard of retrieval practice - you may even have used it - but here’s a refresher for your NQT year.

Trying to remember

Retrieval practice is a way to organise our memories, making them a lot easier to find. It is the act of rummaging around in our long-term memory in order to rediscover something we’ve forgotten.

Unlike handbags, however, long-term memory is self-organising. The very act of searching for a memory strengthens that memory. It’s as if, each time we try to remember something, our brains file it in the “this might be useful” folder, making it easier to retrieve the next time.

If we keep practising retrieving a specific memory - the seven times table, for example - our brain gets the message that we definitely want to remember this stuff. The memory gets promoted to the “definitely useful” folder and, ultimately, with enough practice, to the “I know this automatically without even thinking” folder.

If we don’t practise trying to find a memory, the brain reasons that it can’t be that important, so it sinks down to the heap of other unsorted, unloved memories in the deep recesses of the mind. It’s in there somewhere; it’s just the devil of a job to actually find it.

Simply put, retrieval practice is the process of actively trying to remember something.

This has profound implications for the classroom. As teachers, we want our students to remember all sorts of different information. We therefore need to give them lots of opportunities to search their memories, without any priming from us, so their brains get the message that what they are trying to retrieve is important.

But for this process to work, there has to be an element of struggle; it has to be at least a little hard to remember. This is why re-reading notes is such a poor way of revising for an exam; it’s too easy. The same problem occurs if we re-teach something right before retesting.

Of course, it’s easy to (briefly) remember something when you have just been told it, in the same way that it is easy to find something in your bag when you’ve just put it in there. It’s finding it a week or a month later that really counts.

So what should retrieval practice look like in the classroom?

Giving students quizzes is the most obvious approach. To be most effective, these quizzes should include a mix of questions from past topics as well as the ones currently being studied. Quizzes can be multiple choice, or involve writing short answers on a whiteboard, or use an app such as Plickers. You could start lessons by playing Jeopardy (“If magma is the answer, what is the question?”). You could ask students to match vocabulary to definitions, or give them the definitions and have them recall the vocabulary, or, harder still, give them the vocabulary and have them write the definitions.

Again, to be most effective, this should include recall of information that was learned weeks, months and years ago, not just what is currently being studied.

Whatever form retrieval practice takes, it should be low stakes and low stress. This is about strengthening memory, not about assessment - let alone grading.

If you do this, it is possible you may get some confused glances from colleagues. As effective as retrieval practice is, some corners of our profession remain ambivalent about it. Many teachers have a strong negative reaction to what they see as mindless drilling.

Anything that might be perceived as rote learning is anathema, the very worst kind of educational practice. They view it as regurgitation without understanding. See, for example, the furore surrounding the idea of learning times tables by heart. There is a deep aversion to students memorising things without exploring them.

But rest assured, the ultimate goal of retrieval practice is for students to be able to understand what they know and be empowered to use that knowledge in creative ways. When students really know something, they can use that knowledge to think critically and transfer it to new contexts.

Self-organising memory

The journey to deep learning starts with shallow learning. Retrieval practice is a powerful tool for freeing students to think for themselves; when key information can be remembered automatically, students have so much more mental capacity to work with.

Contrast, for example, the child who knows automatically that 5 + 7 = 12 with the one still working this out on their fingers. The first will have spare capacity in their working memory to think about how place value operates when learning the vertical algorithm for addition. The second is too busy counting to be able to think about columns.

Or how about the young person who knows Macbeth really well, including

some quotes by heart. They are much better placed to write a thoughtful essay than the one who doesn’t. What’s more, once internalised, those quotes belong to that student, becoming a part of them and their intellectual capital forever, not just for tests and school.

The self-organising handbag is, regrettably, some way off. The self-organising memory is already here, so we should exploit its full potential by embedding retrieval practice into our teaching. Let’s strengthen our students’ memories and free them to think.

Clare Sealey is a primary headteacher in London. This article was published as part of the ‘Tes guide: Your first year in teaching’, a guide covering everything you need to know as an NQT about pedagogy and staying healthy.

Order your copy of the guide now. Order now.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters