Almost every class has one.

An artist.

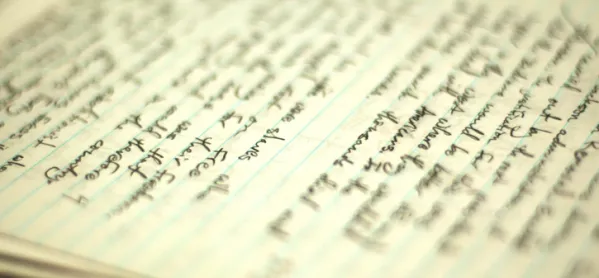

A student whose book is perfectly highlighted, their handwriting beautifully rounded, not a crossing out, scribble or doodle in sight.

Quick read: How to reduce your marking in primary

Quick listen: How misbehaviour can be a sign of language disorder

Want to know more? Should we scrap classroom seating plans?

Their attention to detail is boundless and whenever anyone, be it a parent, head of department or SLT member, happens to look at your books, you hand theirs over with pride, safe in the knowledge that anyone would be blown away by their commitment to their work.

But when they are creating their masterpieces, can they also write a truly perceptive essay on A Christmas Carol?

How many of those students creating colour-coding charts are also giving what you are saying about how to improve their full attention?

Effort and attainment aren’t the same thing

It is not simply that it takes students’ focus away from the actual content of their work, but it also gives them a false sense of security about their own effort and, ultimately, their attainment in a particular subject.

Their friends will see their book and admire it, the SLT member carrying out the learning walk will be reassured that this student is putting in the work, their parents will be impressed by the painstakingly colour-coded, annotated quotes (never mind the fact that they’ve identified a verb as a noun, a metaphor as a simile and their analysis is weak).

It is very easy to conflate effort with attainment; and allowing students and those closest to them to believe that they are the same (or lead to the same outcome) is unfair to them, and detrimental to teachers.

I know that I have praised students for the beauty of their books. I also know that I am just as likely to find amazing content in the book that looks messy. Yet my preconceptions persist.

As professionals, we have to work hard to overcome our immediate reaction to the aesthetics of a book. Yet rarely do we notice our unconscious bias towards the piece of work that looks neat and uniform.

How can we teach our students not to value the presentation of a piece of work as much, if we are not aware that we are implicitly passing our own bias on to them?

We cannot simply order all teachers, students and parents not to appreciate a well-presented piece of work. Nor should we. We spend weeks with new classes setting expectations, including the way they present their work.

When students take neatness too far

It is important to set these expectations and stick to them. However, we need to be aware of when we, or our students, have taken this expectation too far.

We need to be vigilant about when the function of a neat book (to be able to read and look through it clearly and easily) stops and the distractingly, unnecessarily decorative starts.

Tolerating the unnecessary decoration as a particular student’s quirk, or using the opportunity to decorate work as a reward, reinforces students’ notion that their work is somehow better if it looks good.

For some students, the beauty of their work is a short cut to praise.

Therefore, we need to cut off the short cut: to think about the language that we use in the classroom. In our students’ Instagram-filtered society, presentation is all - so let’s stop playing into it in the classroom.

Make a conscious effort to praise the content, not the form.

Sarah Tidy is an English teacher and the head of public speaking at Ratcliffe College in the East Midlands