‘Why we’re using symbols to mark students’ work’

Share

‘Why we’re using symbols to mark students’ work’

Our decision to stop grading work in key stage 3 had been a success last year. There was no longer the fixation with the numbers at the foot of the page, and whispers of “What did you get?” were a thing of the past.

What began as part of my five-month research project with Year 7 English, Year 8 French and Year 9 geography classes had prevented students from comparing their work with others and, instead, forced them to engage much more with what the teacher had actually written.

As a result, comment-only marking became school policy for KS3.

'Ownership of learning'

But then we began to think: how about encouraging the students to recognise their own mistakes, without comments?

Substantial evidence reveals that the best feedback encourages students’ ownership of their own learning. As educationalist Professor Dylan Wiliam says, "effective feedback should be more work for the recipient than for the donor". With that in mind, we tested a new approach with the KS3 summer exams.

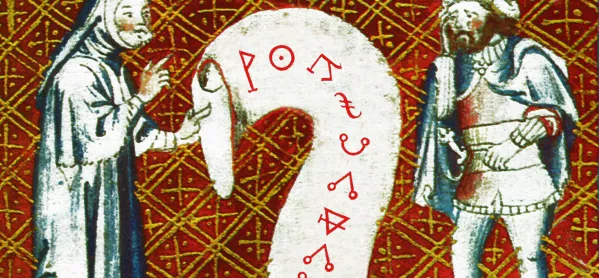

The summer papers had to receive a summative grade, so we instead put an end to all teacher comments other than a brief line of genuine praise. We had given the marking criteria to the students before the exam but, on this occasion, they also received a sheet of symbols with their returned papers. The definitions alongside the symbols explained the seemingly mystical annotations that adorned the margins – symbols identifying that a particular line contained a structural problem, unclear expression or flawed logic, for example. The precise nature of the error, however, was something the students had to determine.

Initially, the students were somewhat surprised. Where were the comments they had come to expect? Still, the tendency they had developed towards reading comments carefully and reflecting on their errors was a transferable skill. With a subtle nudge in the right direction, the students began identifying error after error.

Later in the feedback session, students were given a compiled list of common errors across the cohort, such as “imagery is clichéd or inappropriate”. This gave more support to those finding the task a challenge, but it also allowed students to identify the one or two less-visible errors. By underlining all the errors they had made, students could better understand how the marking criteria had been applied. Their next step was to correct the errors and draw up a list of related targets for a subsequent piece of work and explain how they would achieve those targets.

'Time-saver'

Staff agreed that this approach had led to much better engagement with the marking criteria and individual corrections. They also said it saved valuable time when marking the papers. We will, however, introduce a little more distinction for some symbols and allow some discretion as to whether more than a few words are provided for the least-able students.

We are also discussing whether to return the papers without the grades. The students would then go through the same process but grade themselves at the end. Upon later receiving their actual grade from the teacher, the students might be asked to explain the disparity between the two.

This may seem quite a challenge, but preparing students in the right way during the year might just allow for some of the best feedback possible and with less time spent on teacher marking.

Antony Barton is head of English at Putney High School in London. He tweets @MrABarton