The 6 steps to hitting your target

Emma looked at her targets. She then looked at the targets she had set her senior leadership team. Next, she looked at the targets that had been set for the heads of department.

She paused. Already, the number of targets set in her school seemed a little…excessive. But Emma was not yet done.

She looked through the targets each head of department had set each teacher. This was a large secondary school - there were many, many staff. There were many, many targets.

And then she looked at the targets those teachers had set their teaching assistants.

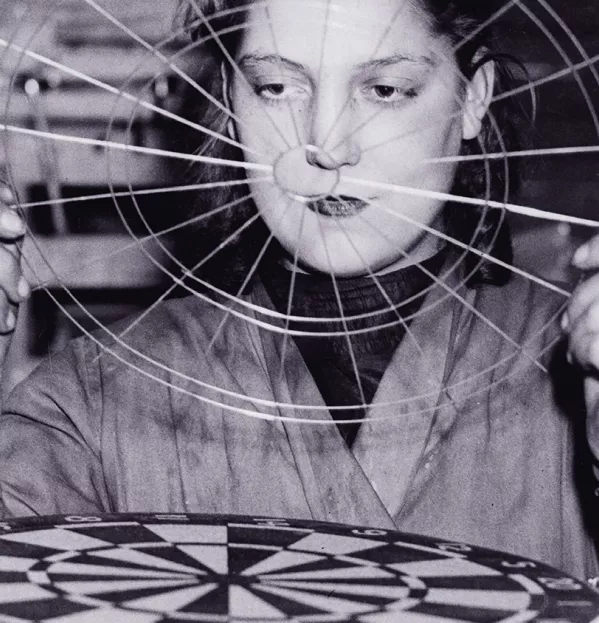

Finally, she looked at the targets the teachers had set their pupils. And that the pupils had set themselves. There were term targets. Annual targets. Target grades. Pastoral targets. Targets for targets.

Not once, she thought, have we taught anyone to set targets; not once have we trained anyone in it. And not once have we really thought about what best practice for target-setting looks like.

This, it suddenly dawned on her, was a rather big problem.

We set targets all the time in schools. While teachers are masters of planning to meet collective learning goals, and in helping students to achieve them, when it comes to individual targets for staff or pupils, particularly pastoral or behaviour goals, it can be like in the fictional school above: it is all done automatically with little attention paid to research on goal-setting. And the research is plentiful.

Admittedly, while goal-setting has been studied within educational contexts, most of what is known is drawn from non-educational sources. But the strength of the research lies in the varied methodologies used, and goal-setting theory is perceived as both reliable and valid.

So let’s join some dots. Our goal: to make goal-setting more effective in schools.

If we seek behavioural change, this doesn’t occur simply through wishful thinking. The person - whether it is ourselves or another - needs to know and understand the behavioural change desired or required.

We could just tell a person, or ourselves, what we want to achieve and leave it at that. In a school, we could just tell teachers to be better; students to get higher grades; the catering staff to make nicer food. We could just say: “I want to lose weight.” But this approach would not get you very far. Most of us understand that goals need to be specific and the route carefully planned. This is what people try to do when they set a New Year’s resolution. “I will lose a stone by Easter and go to the gym each week and eat better to achieve this”; “I will reduce my mobile phone use by turning it off at 8pm every night.”

And this is what can often happen in schools: “Michael, we need a clear behaviour chart by Friday”; “Louise, let’s aim to get this piece of work finished by the end of the lesson.”

Alas, these goals often fail. To set truly effective goals, we need to do a lot more than we do currently.

Edwin Locke, the American psychologist and pioneer of goal-setting theory, suggests that, for a person to be able to achieve their goal, they must be committed to it, have the requisite ability to attain it (and, if not, acquire the ability first), and be free from conflicting goals (Locke and Latham, 2006).

Why do goals, constructed properly, work? Part of the reason is motivation. If the goal is set properly, our motivation increases, so procrastination and the tendency to self-handicap reduces because people who are committed to their goals are far less likely to abandon or delay behaviours that help to achieve them.

But another reason is resilience: when goals are carefully planned and setbacks considered, people are then in a position to negotiate a path through any problems that might arise.

Finally, goals help to raise levels of self-efficacy - the confidence people have in their ability to complete a task. Success breeds success: each time we reach our goal, we become better prepared to face the next one.

Is Locke’s description enough for us to go on, though? From that, can we put better targets in place for staff and pupils?

Owain Service and Rory Gallagher are part of the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team (sometimes referred to as the Nudge Unit) and have been looking at how people might become more effective at positively changing their behaviour through setting and pursuing goals. They narrow the list of strategies down to just a handful of the most important factors: setting the right goal (and only one at a time), planning, commitment, rewarding, sharing and feedback (Service and Gallagher, 2017).

These factors have been tested in a number of environments, including education. For example, a trial of goal-setting in UK further education colleges found that the introduction of formal goal-setting sessions in addition to subject-specific lessons increased achievement in English and maths (Hume et al, 2018).

So let’s assume you have taken Locke’s recommendations on board; now let’s take the Nudge Unit’s points in turn. Let’s build a research-informed goal-setting approach.

1. Set the goal

Who sets the goal? Self-assigned goals increase feelings of autonomy and motivation, yet goals assigned by others can be more effective: for example, teacher-assigned goals have been found to be more effective than pupil-assigned goals because students have been found to struggle to consistently pursue goals that they have set for themselves (Ariely and Wertenbroch, 2002).

In the early stages, it’s advisable to use teacher-allocated goals until students become clear about what good goals look like. In addition, younger children are naturally less well equipped to set their own goals so teachers should play a bigger role in their selection.

When setting goals, there is a tendency to make them vague and open-ended. There is also the danger that the goal is too big and unmanageable, or there are simply too many goals for people to cope with. This can happen because schools are busy places and setting a goal seems so natural - “do x by y”, “make sure x happens before you do y” - so we don’t tend to give it much thought.

But setting a single goal is much more effective than setting multiple goals, and the more specific we make the goal, the easier it becomes to focus attention on it.

In secondary school specifically, then, we need to be conscious of how many goals a single student may be set and whether any are competing with each other; that’s going to require departments to talk with each other, or at least the form tutors, who can act as overseers. This is particularly important for pastoral goals: how many goals is a single student aiming to tick off?

And goals such as “work harder” or “do your best” are simply too vague, as is “behave during every lesson”. However, “raise my current grade from a 5 to a 6 or a C to a B” or “move towards zero sanctions for calling out” allows students to hone in on what is required and measure any change. Working out what exactly you want to be achieved, as the goal setter, is crucial to secure behavioural change in the person working towards the goal.

Next: deadlines. Not only does the person need to know where they are going and have a route to get there, but they also have to know when they need to be there by. This helps with route planning, but also with another crucial part of goal-setting: breaking down large goals into chunks or subgoals, either by time allocation or by breaking them into individual components.

In a study conducted by Albert Bandura and Dale Schunk, children struggling with maths were given intervention booklets consisting of 42 pages of 258 subtraction problems. The children were split into two groups. One group was advised to complete six pages in each of the seven allotted sessions; the other group was given no such advice and could move through the booklet as they pleased during those sessions.

The group who were given the advice not only progressed more rapidly, but they also showed a greater enjoyment for maths at the end of the seventh session (Bandura and Schunk, 1981).

This makes intuitive sense; breaking down, say, a 2,000-word essay into sections with approximate word counts is much less arduous than tackling the task head-on without guidelines.

The second option, breaking goals down into components, follows the theory of marginal gains. The principle underlying the technique involves deciding on individual elements that will help with goal completion. A student who wants to increase their overall grade might break the goal down into subject knowledge, exam technique and time management; improving all three components by just a small amount is likely to affect the larger goal.

2. Make a plan

Goals need to be challenging, but this doesn’t mean that the plan should be complicated. In fact, it shouldn’t be complicated at all (put away your Gantt chart).

There’s a good reason why the 5:2 diet is so popular: it’s simple, you don’t have to bother counting calories, you just eat what you want for five days and then fast - or severely reduce your calories - for two nonconsecutive days. The fasting days might be hard, but they’re not complicated, they eventually become a habit requiring little conscious effort. And habits - at least the good ones - are vital to successful goal completion. (Take note if dieting was one of your New Year’s resolutions.)

So if you want teachers to meet their goals or students to meet theirs, helping them to form habits is essential. Planning does that: it makes a cognitive connection between the goal and the actions required to achieve it. If you plan for something to be heavily routined, then this helps habit formation. Think about a new exercise regime: if you just say you will go to the gym three times per week, then that is a plan of sorts. But if you say you will go to the gym before work on a Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and be at the gym by 6am on each of those days, you can help the behaviour to become cue-dependent.

Similarly, the student who wants to improve by adopting more useful study habits might plan to study at home every evening after dinner. In both cases, the cue is in place (before work; after dinner), and the behaviour eventually becomes habitual, even resulting in feelings of guilt if the action isn’t carried out.

Unfortunately, there is little consensus about how long a habit takes to form.

Schools are ideal environments in which to nurture useful habits, be it falling silent when instructed to do so or using appropriate revision techniques. We’re pretty institutionalised to be habit-forming.

Psychologist Gabriele Oettingen suggests people should also incorporate mental contrasting (or “doublethink”) into their planning (Oettingen, Hönig and Gollwitzer, 2000). This is the process by which people anticipate the obstacles and setbacks they might face, allowing them to be more prepared and far less likely to abandon the plan or place imaginary obstacles in the way.

If you are on a weight-loss drive and know that every time you go to the supermarket you come out with a four-pack of doughnuts, then perhaps not going to the supermarket would become part of your plan and you could do online shopping instead.

Likewise, if you are working with a student to improve their behaviour, then you need to foresee with that student where the goal is at risk of being derailed: perhaps a particular friend helps instigate trouble, or certain dietary habits or routines (staying up late, for example) exacerbate the problems.

3. Make a commitment

Goals often fail because people aren’t committed to them. This is easier to avoid

if they have picked the right goal and have planned effectively, but, even then, people can struggle to stick at it.

According to Service and Gallagher, publicly declaring an intention to achieve a goal increases the likelihood of success; after all, a declaration is like a promise to others that we intend to do something, and we are socialised from an early age to believe that we should keep our promises.

Commitments and declarations link present intentions to future actions, circumventing what is known as present bias (the tendency to opt for pay-offs that are closer to the present time rather than waiting for bigger pay-offs later). Read, Loewenstein and Kalyanaraman (1999) found that if people make a formal commitment in the present to do something in the future, they are much more likely to follow through on their intentions.

There are many ways to publicly declare our intentions, such as signing a pledge or telling people close to us what we are intending to do. Public health campaigns, such as “dry January”, encourage people to commit to give up alcohol for a month following December’s excesses, often coupled with a request for sponsorship for charitable causes to help solidify the commitment.

But in schools, think carefully before making public declarations. While declaring intentions can help in the pursuit of goals, remember that some students might find this uncomfortable and may become anxious. It might be more appropriate to allocate goal partners or referees. Another useful method is to have students formally sign a pledge to pursue their goal; these can be kept in a safe place or attached to a “commitment board” (the latter has been used by members of the Nudge Unit to help them with their own goals).

4. Use rewards strategically

Small rewards at critical moments, either when a goal or subgoal has been completed, can build good habits that contribute to goal success in the future. The nature of the reward will often depend on the individual, and how committed and motivated they are.

Of course, rewards shouldn’t undermine the progress that has already been made - rewarding a weight goal being reached with a huge bar of milk chocolate, for example, would be counterproductive.

One of the main problems with rewarding positive behaviour is that it can backfire in some circumstances. This is often the case when financial or other tangible rewards are offered. As a general rule, if the person pursuing the goal has an intrinsic, personal and self-motivated desire to succeed, certain types of reward will risk “crowding out” this motivation.

One study found that fining parents who arrived late to pick up their children from daycare actually increased the number of late arrivals (Gneezy and Rustichini, 2000). Why should this be the case? It would appear that prior to the introduction of the fines, parents felt a moral obligation not to be late, but once they knew that they would be fined for not arriving on time, this moral obligation transformed into a financial transaction.

In a similar way, if someone is offered a financial reward for doing something that they enjoy (and there was previously no financial incentive), enjoyment then becomes work and motivation can dip.

In schools, be mindful of this effect: any incentives for meeting goals should be carefully thought through.

5. Share goals

Goals tend to be personal, but they can go beyond the individual so we mustn’t neglect the importance of social interactions.

Sharing goals with others or appointing someone to oversee goal pursuit increases the likelihood that the goal will be achieved. This is one reason why support groups can be so successful for people struggling with addiction or mental health problems, and why couples who share goals (such as giving up smoking) are more likely to succeed than those who go it alone.

Asking someone to oversee our goals is particularly powerful; Ayres (2010) found that appointing a goal “referee” increased the likelihood of success by up to 70 per cent.

Sharing not only increases commitment, it also garners support and encouragement which, in turn, increases the desire to succeed. In schools, we need to be careful again, as with public declarations, to not cause children anxiety. Letting pupils share goals with trusted friends, or form partnerships of their own choosing to act as goal referees for each other, can be useful.

6. Focus on feedback

As people work towards their goal, they need to know where they are in comparison with where they want to be. Feedback should be timely, specific, actionable and focused - there’s no point offering feedback so late that it doesn’t allow us to change direction, adapt strategies or jettison habits that are holding us back. This is why many corporations are moving from annual employee reviews to twice-yearly, or even more regular, reviews.

Feedback needs to be specific or personal. People need to know if they are off track and they then need actionable guidance on how to get back on it.

Teachers are more than familiar with the use of effective feedback; indeed, the Educational Endowment Foundation has highlighted the vital nature of providing the right feedback for academic outcomes. But do we always apply this to our goal-setting for those we line manage, or for our pupils in non-academic situations? Have we set the child a goal of no sanctions during the week, but only checked in with them at the end of the week to see how they had done? Have we told them to finish a piece of work by the end of the lesson, but not regularly checked in to see if they were encountering any barriers?

Obviously, following all of the advice above will not mean every goal you set will suddenly be met. It won’t ensure easy journeys towards goals, either. But it will mean goal-setting will be more successful than it would otherwise be. And that, I would say, is a pretty decent goal to have.

Marc Smith is a chartered psychologist and teacher. He tweets @marcxsmith

References

* Ariely, D and Wertenbroch, K (2002) “Procrastination, deadlines and performance: self-control by precommitment”, Psychological Science, 13/3: 219-224

* Ayres, I. (2010) Carrots and Sticks: Unlock the power of incentives to get things done, Bantam Dell Publishing

Bandura, A and Schunk, DH (1981) “Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3/41: 586-598

* Gneezy, U and Rustichini, A (2000) “Pay enough or don’t pay at all”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 3/115: 791-810

* Gollwitzer, PM and Sheeran, P (2006) “Implementation intentions and goal achievement: a meta-analysis of effects and processes”, Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38: 69-119

* Hume, S, O’Reilly, F, Groot, B et al (2018) Retention and success in maths and English (The Behavioural Insights Team/Department for Education)

* Locke, EA and Latham, GP (2006) “New directions in goal-setting theory”, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5/15: 265-268

* Oettingen, G, Hönig, G and Gollwitzer, P (2000) “Effective self-regulation of goal attainment”, International Journal of Educational Research, 7-8/33: 705-732

* Read, D, Loewenstein, G and Kalyanaraman, S (1999) “Mixing virtue and vice: combining the immediacy effect and the diversification heuristic”, Journal of Behavioural Decision Making, 4/12: 257-273

* Service, O and Gallagher, R (2017) Think Small: the surprisingly simple ways to reach big goals (Michael O’Mara)

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters