Are new GCSE targets having ‘a racist impact’?

They were the changes designed to tackle the “soft bigotry of low expectations” and expose the schools that ministers said were failing black and ethnic minority pupils.

But now a leading professor of race studies has claimed that the introduction of tougher GCSE benchmarks for schools - aimed at encouraging them to achieve better results - has actually had “a marked regressive and racist impact” that “served to maintain black disadvantage”.

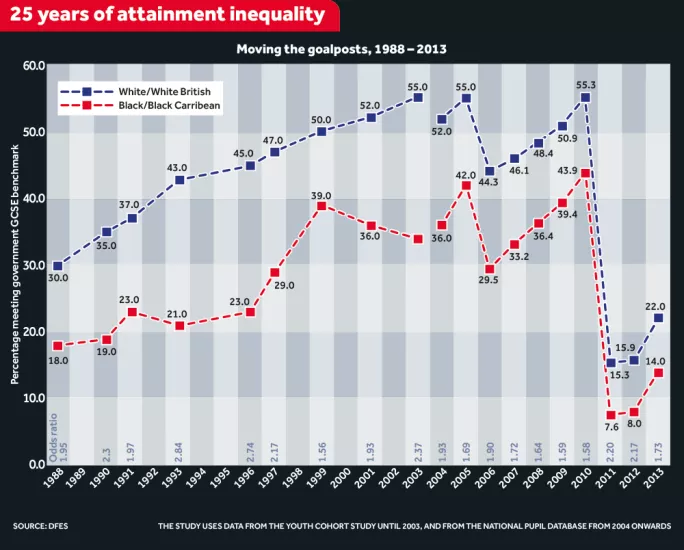

The accusation comes in a paper, “Moving the Goalposts: education policy and 25 years of the black/white achievement gap”, due to be published in the British Education Research Journal, which examines the gap between the GCSE attainment of white students and their black Caribbean peers over a 25-year period, starting from 1988, when the qualification was introduced.

Initially, the government benchmark was for pupils to gain five GCSEs at grade C or above but during these two-and-a-half decades, the government twice introduced tougher targets, designed to increase academic rigour.

First, in 2006, there was what the Department for Education and Skills referred to as the “gold standard”: five GCSEs at grade C or above, including English and maths. Secondly, in 2011, the English Baccalaureate (EBacc) was introduced.

The researchers examined the odds of white British students achieving the benchmark, relative to their black peers. When the resulting odds ratio is “one”, the two groups are equally likely to meet it. A higher number means white pupils are more likely to achieve it, with “two” meaning white pupils are twice as likely to do so.

The paper finds that, in both cases, the introduction of a new benchmark increased the odds ratio in favour of white pupils, compared to black Caribbean pupils.

The expansion of the GCSE benchmark to require English and maths resulted in the ratio rising from 1.69 to 1.90 between 2005 and 2006, before falling for four consecutive years.

The academics suggest the initial increase in the gap could reflect the use of tiered papers in English and maths, where a disproportionate number of black students are entered in the lower tier.

When the EBacc was introduced, the odds ratio rose from 1.58 to 2.20, a level not seen since 2003, before then starting to fall again.

The academics suggest this could reflect the under-representation of black Caribbean students among those studying the more academic subjects that make up the EBacc.

Decisive and immediate impact

Despite talk of closing the gap between the two groups, the odds ratio has remained above 1.5 during the whole 25-year period, meaning that in each year white pupils were at least one and a half times as likely to achieve the benchmark.

“Changes to the headline measure of educational achievement have a decisive and immediate impact,” the researchers write. “In England to date such changes have had a marked regressive and racist impact; redefining the benchmark has led to a wider black-white gap.”

David Gillborn, director of the Centre for Research in Race and Education at the University of Birmingham, who co-authored the paper, says: “This is a story about institutional racism, but those processes work for other groups as well. Any time you raise the bar, you will raise the inequity for any disadvantaged group because of the way they are distributed through the system.”

But these benchmarks are designed by the government to hold schools, rather than pupils, to account.

So does this research show that the tougher benchmarks disadvantage black Caribbean pupils? Or, conversely, do they shine a spotlight on the system’s failings and potentially benefit black pupils by pressing the need for schools to do better?

Gillborn believes the former, arguing that when employers and universities make decisions about applicants, they are influenced by what the government says the benchmark is - thereby disadvantaging groups who are less likely to meet it. However, he acknowledges his evidence for this behaviour is anecdotal. “It’s nice to be seen to say you are raising the bar, and being tough, but these are thousands of children whose chances in the labour market and higher education are being fundamentally rewritten, sometimes literally overnight,” he claims.

“These kids did not suddenly get stupid overnight. They are being held to a threshold that has not officially existed before, and which they have a less of an opportunity to get.”

But Sir Michael Wilshaw points out that the GCSE benchmarks “hold schools to account rather than individual children”.

The former chief inspector of schools dismisses the argument that “moving the goalposts” has a “racist impact”, as “nonsense”.

“We must not start patronising children and creating artificial benchmarks for particular racial groups,” Wilshaw, a former Hackney comprehensive head, says. “We have to make sure that they get the right teachers.”

He adds: “I think we are going down a really bad road of not treating children fairly if we have lower expectations of one group over another. It’s not fair to the children and it’s certainly not fair to society.”

Treating children fairly

It is a view echoed by Tony Sewell, chief executive of Generating Genius, which works to widen access for young people from disadvantaged homes to top universities.

He recognises the gap between black Caribbean pupils and white pupils - but notes there are other groups of black children of different heritage who perform much better - and is worried by any implication that the benchmark should be “made easier or dumbed down in order for them to succeed”.

“I do think we have got to attribute the underachievement to a range of factors, rather than the government trying to make the education system much more accountable and something that has rigour and internationally can stand up,” he says.

Sewell argues that the priorities for addressing the attainment gap should be looking at pupils’ family situations, peer group pressure, and the transition from primary to secondary school.

A DfE spokesperson said: “We are driving down the attainment gap between all disadvantaged pupils and their peers. The attainment gap has been steadily decreasing since 2011.

“We are determined to ensure that all children, regardless of their background, get the education they deserve. In 2015-2016 black pupils had higher than average Progress 8 scores, showing that our reforms are working.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters