Are we making a mockery of key stage 1 Sats?

Over the past few weeks, thousands of pupils have been spending hours indoors, after school, hunched over desks, staring at previous years’ test papers. But they have not been revising for GCSEs or A levels. In fact, they are not even secondary pupils. These are infants - just six and seven years old - and they have been preparing for key stage 1 Sats.

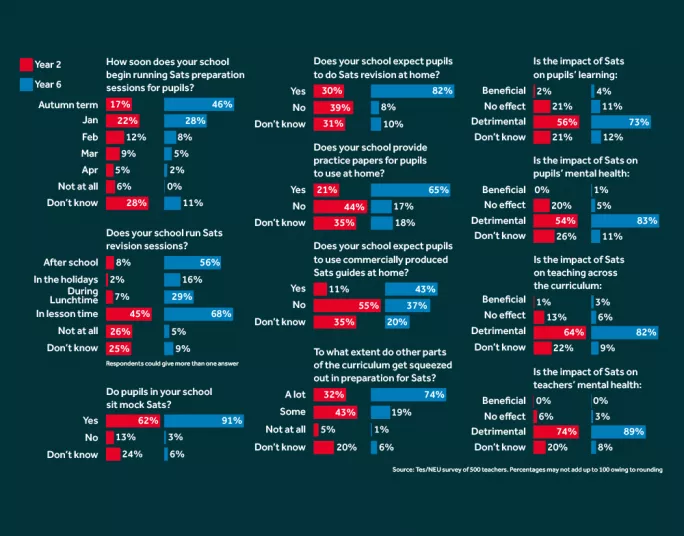

A new survey, conducted by Tes with the NEU teaching union, suggests that one-in-five schools have been sending their Year 2 pupils home with practice Sat papers.

One parent in Cambridgeshire who highlighted the problem explained that his daughter’s school suggested parents buy a pack of revision guides for KS1 Sats during a parents’ meeting.

“It is a good school,” he says. “I’m very happy with the school - and not complaining about them. But for the KS1 Sats, they have had more preparation than I did for GCSE. It’s crazy.”

And it doesn’t stop there: 62 per cent of teachers say their schools hold mock KS1 Sats and 30 per cent say their schools ask Year 2 children to revise for Sats at home.

“I live in fear of being moved to Year 2, as I disagree with the way Sats have taken over and completely ruined Year 2,” one teacher confessed in response to the survey.

Parents also appear to have been gripped by a fear of failure when it comes to Sats for infants. Private tutors are targeting them by advertising revision sessions for seven-year-olds online and publishers are pumping out guides for worried parents.

Squeeze on the curriculum

Perhaps unsurprisingly, most teachers now believe that the tests are detrimental to both pupils’ and their own mental health (see page 18). And that burden is something that primary experts do find shocking.

“I am stunned,” says author and teacher trainer Sue Cowley. “We have moved so far away from what these tests have been presented to us as checking.

“In theory, they are a light check on how kids are getting on. But they have turned into an industry. You go and look at The Book People [online bookshop] and there’s all these ‘Prepare your kids for Sats’ books - a whole industry has developed around it.”

The big question is why? No employer or university will ever ask an applicant how they fared in their KS1 tests, at an age when they were still being put to bed with a story and a teddy bear.

No primary school league tables are compiled with KS1 Sats results. In fact, if anything, the incentive ought to work the other way around - low results in Year 2 would make it easier for the primaries to do well on increasingly important progress measures, when it comes to Year 6.

The actual test results in KS1 will never be reported to the government anyway. The tests may be externally set, but since 2005, they have only been held to inform teachers’ official assessment of pupils.

So how have these supposedly low-key tests become so pressurised that three-quarters of teachers say they are leading to the rest of the KS1 curriculum being squeezed?

It was anger over the effects of testing on young children that led to KS1 Sats being downgraded 13 years ago. A Tes/YouGov poll in 2003 found that more than a third of pupils were stressed and that one in 10 was losing sleep because of the tests.

Soon afterwards, the government acted and announced it was moving away from formal timetabled national tests for seven-year-olds to lower-stakes tests with unreported results that would only be used to inform teachers’ assessment of pupils.

Teachers now say that the pendulum has started to swing back. Since a new, tougher national curriculum was introduced in 2014 - with a corresponding rise in the demands of the tests, which are still externally set - the pressure has increased noticeably.

“Children are becoming numbers and teachers are talking to six- and seven-year-olds about test technique rather than a love of learning,” one teacher responding to the latest Tes/NEU survey comments.

Another is more blunt: “My mental health is suffering and I need to choose to leave Year 2 or stop caring - neither of which I want to do.”

More than 650,000 Year 2 children will sit the tests in maths and reading at some point next month. There is also a non-statutory test in spelling, punctuation and grammar.

The KS1 tests are no longer as formal as those in KS2. They do not have to be taken on particular days, so long as they are taken in May. They are not strictly timed. They are also marked internally and can be taken by groups of pupils on different days.

But over the past two years, the standard the government expects from Year 2 pupils has deliberately been set higher. And that raising of the bar can be seen clearly in the teacher-assessment results drawn from the tests.

In 2016, the first year of the new Sats, 74 per cent reached the expected standard in reading and 73 per cent did so in maths.

It was quite a drop from the previous system, in which 90 per cent of pupils reached the then expected level 2 in reading and 93 per cent did so in maths.

“It will have come as a shock,” Nansi Ellis, assistant general secretary of NEU (ATL section), says of the new standards. “The curriculum changed and teachers feel that in order to help kids do the best they can in the tests at KS2, or KS1, they have to prepare them for it.”

Local contagion spreading

Predictably, the survey of 500 teachers carried out by the NEU and Tes found even more test preparation in Year 6 - with 91 per cent running mock Sats. The future of whole schools, and the jobs of their teachers, have become reliant on the basis of a handful of 45-minute tests taken by 11-year-olds. So perhaps the pressure to do well in Year 6 is spreading to other year groups within primaries? Do heads believe that driving pupils to achieve higher test results in KS1 would lead to improved outcomes for 11-year-olds?

Some think the test-preparation contagion could also be spreading sideways between schools, as well as downwards within them. There is no official guide as to what counts as acceptable test preparation. So if one school starts to do more, will its neighbours be able to resist the temptation to follow suit?

“Many schools will do a lot of moderation of tests and assessments between schools in a cluster,” says Ellis, reflecting on the KS1 problem. “If you go into a school and you are looking at the children’s work, you get chatting. You may find that school is doing these mock Sats and, particularly if you are in an Ofsted window, you think ‘maybe we should be doing that, too’.

“If you are in competition with a school down the road and they are doing something, then it all gets shared, everyone talks.”

Familiarising children with the type of questions they will face is already seen as unremarkable, even sensible. So has sitting mocks in KS1 now also become normalised, as schools try to keep up with each other?

One teacher responding to the survey says: “In the past, we have tried to make [KS1] Sats as relaxed as we can. New deputy and head this year: first year we have done mocks. Before, it was all integrated into lessons.”

And then there is Ofsted. The watchdog wants to see children doing well, and with greater expectations in all year groups, the pressure is on to boost pupils’ attainment early.

The inspectorate often raises KS1 results in its reports on primary schools. “KS1 is weak, as too few pupils achieve both the expected standard and greater depth in reading, writing and mathematics,” an Ofsted report on one North West primary reads.

However, the watchdog’s leadership is also clear that test preparation should not dominate lessons.

“Ofsted’s chief inspector, Amanda Spielman, has repeatedly expressed concerns about schools that overprepare pupils for exams at the expense of a deep and rich curriculum,” a spokesperson says. “This applies equally across all phases of school, including KS1.”

The DfE takes a very similar line, saying that there is “no need” for schools to encourage Sats revision and mocks, or for pupils to experience stress over KS1 testing.

Nevertheless, there have been mixed messages from Sanctuary Buildings. In 2013, the department said that if a Reception baseline were introduced, it could consider making the KS1 assessments non-statutory. In the end, it decided to introduce a non-statutory Reception baseline and keep the KS1 tests as they were. But in 2015, Nicky Morgan, the then education secretary, began talking about a “rigour revolution” and the need to ensure the KS1 assessments were “robust and rigorous”.

Her “rigorous” stance appeared to be a response to the vast majority of primaries choosing a Reception baseline assessment that was based on teachers’ observations rather than tasks or tests.

That attempt at introducing a Reception baseline collapsed in 2016. But the government has just awarded a contract for the new baseline assessments to be developed - this time promising it will scrap KS1 tests if it is successful. So could this flip-flopping have fuelled schools’ distrust over whether KS1 really is lower stakes than it used to be?

Parents are similarly confused about the Sats. Mock tests may be done by schools, but many of the revision practices rely on parents. And some feel stuck in the middle and fear that their involvement only ratchets up the pressure surrounding the testing. “I was very unimpressed to be sent what were essentially past papers for my seven-year-old to do over the holidays,” says one mother in West Sussex. In her case, the school also asked parents to work through the “quizzes” that their children had done in class, when they got home. Parents were expected to make sure the new working was done in a different colour and that the quizzes were returned to school.

“My concern is not only the amount of work the children are expected to do in the holidays, but the involvement of parents,” the mother says. “It starts creating a Sats competition [between parents], which I don’t think would happen if it was handled in the classroom. I haven’t gone through the paper, but part of me is finding it difficult not to. I want to support my child. I’m prepared to do stuff to support the school. But it is not a useful exercise for him.”

Madeleine Holt, spokesperson of More than a Score - an alliance of parent groups and educational groups - says this internal conflict is common. “In the current climate of fear and results-driven accountability, it is totally understandable why schools feel obliged to increase homework and extra Sats preparation in both Year 6 and Year 2,” she says. “But it puts some parents in a very difficult position. They want to help their child, but they are increasingly uneasy about the pressure even seven-year-olds are now being put under.”

It is also tough for headteachers, who have to juggle the concerns of teachers, parents and Ofsted. “Ultimately, schools know that they will face difficult questions from Ofsted if their KS1 results are significantly below the national average and so, yes, there is certainly a pressure for schools to do well in that sense,” says James Bowen, director of middle-leaders’ union NAHT Edge.

“We have a system currently where everyone is set up in competition with each other when it comes to Sats. It’s a zero-sum game with everyone striving to be ‘above the national average’. I’m not sure that level of competition is entirely healthy.”

But Ellis says trying to buck the system - whether you are a teacher or a head - is not the answer. What is needed is a new system.

“It is really hard for school leaders,” she says. “This is not about evil headteachers putting the pressure on. It’s the system all the way through. We need a radical rethink of the assessment and accountability system. Schools are not being held accountable for the right things. We are being held accountable for a few numbers, in a few bits of a couple of subjects.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters