Carillion, Learndirect… Once again, the reputation of apprenticeships has been seriously tarnished. How can young people, parents and teachers have confidence in a training system that seems chronically unstable?

Last year, we saw the storm bursting over Learndirect, the UK’s largest commercial training provider, responsible for 75,000 students a year. Ofsted found the company to be inadequate, with 70 per cent of its apprentices failing to reach minimum standards of achievement. It then turned out it was in danger of financial collapse.

Then, this year, we had the spectacular demise of construction and services firm Carillion, and along with it the collapse of its apprenticeship programme. About 1,400 unsuspecting apprentices were left in the lurch with their training abruptly suspended.

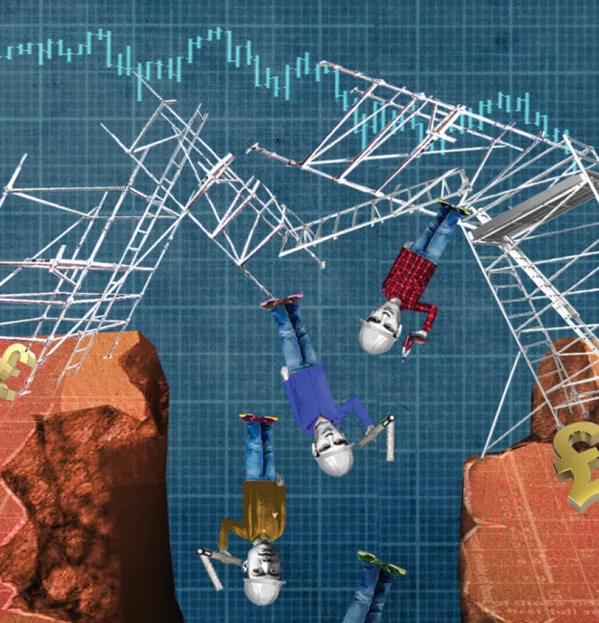

Organisational earthquakes

Many of the individuals caught up in these organisational earthquakes will manage to navigate their way through the rubble and finish their training; other providers will step in, typically FE colleges and charitable training organisations. But the damage has been done. In the public mind, the rickety structure around apprenticeship training has again been exposed. No wonder most young people are sticking to the A level and university route, despite anxiety over student loans.

Apprenticeship scandals are nothing new. Remember Elmfield Training? Most of the training for which it was receiving millions of pounds consisted of little more than giving certificates for skills employees already had. And a year ago, First4Skills went into administration without warning, leaving 4,500 apprentices at risk.

The defenders of private trainers will point out that few go bust and few receive poor Ofsted ratings. They will underline the fact that many colleges subcontract provision to private providers. There’s no doubt that many employers like working with private sector trainers, which are quite often staffed by people who have worked in the industries they supply. But that misses the point. I have no problem with private training companies existing. If people are prepared to pay for private training - just as they are for private schooling or private health - I wouldn’t want to stop them. But why should they receive public money? And why aren’t they more tightly regulated?

It’s time to stop private providers operating, except under strict conditions. We should implement one of the recommendations of the Sainsbury review and ensure that publicly subsidised education should be delivered under not-for-profit arrangements. This way, we could retain those charitable organisations and social enterprises that fulfil an vital role in niche sectors and with trainees who have special needs.

In short, we should keep good-quality providers; just get rid of the profit motive. The quality and reliability of apprenticeships needs to be the number one priority, not their profitability.

Andy Forbes is principal and CEO of the College of Haringey, Enfield and North East London