Check with Maslow before coming down hard on students

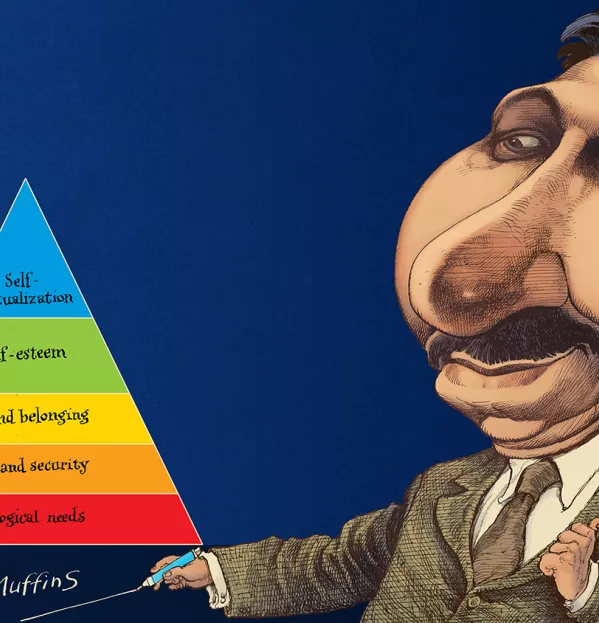

If you’ve ever wondered why thinking about that tray of muffins in the corner of the staffroom is making it hard to knuckle down to your marking, it could be time to reacquaint yourself with the work of Abraham Maslow. Maslow was a pioneer of humanist psychology which, in the middle of the 20th century, became the third force in psychology, challenging the dominance of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory and the new science of behaviourism.

Humanist psychology explored positive aspects of the human mind rather than focusing on why things went wrong. In short, it was about how to be your best self.

In Maslow’s most famous contribution to psychology, The Hierarchy of Needs, we might also find the key to helping the children in your classes become better students.

Maslow believed that human behaviour could be best understood by recognising that we’re all constantly trying to satisfy a number of needs, ranging from basic survival needs all the way up to finding deep-seated psychological fulfilment. Maslow ordered these human needs into a neat pyramid with five tiers, starting with physiological needs such as warmth and hunger, moving up through needs of safety, love and esteem, to the apex of self-actualisation.

What we’re ultimately all shooting for is to become the person we feel destined to be. This end point of self-actualisation will be different for different people. As Maslow states: “In one individual, it may take the form of the desire to be an ideal mother, in another it may be expressed athletically and in still another, it may be expressed in painting pictures or in inventions.”

These needs were arranged in what Maslow termed a “hierarchy of pre-potency”, meaning that until you had satisfied the lower needs, it would be difficult to achieve anything higher up the list. Regardless of where the end point lies, what’s vital to recognise is Maslow’s suggestion that the first needs will “monopolise consciousness” until they are satisfied.

As teachers, we’re faced every day with a group of people whose needs are different and who are at different stages of having those needs met.

It’s worth remembering just what it is that we’re asking students to do when they step into the classroom. They’re expected to sit still, to stay quiet, to control the urge to go to the loo, to control the urge to shout at someone who might be repeatedly flicking their ear, and all while listening to something it’s quite possible they have zero interest in. Add to all that the fact that half of them didn’t get to sleep until gone 2am and may only have eaten a bag of Quavers for breakfast. And then we get angry with them because they’re not giving their full attention.

According to Maslow, before a student can hope to tackle demanding cognitive processes, such as learning new skills or acquiring knowledge, they must first fulfil their basic physiological needs. It’s just no good trying to get a kid who’s tired or hungry to learn that the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides. (To be honest, it’s probably hard enough to get a peppy, well-fed student to pay attention to that.)

Spot the problems early

So, how do we use this knowledge? As far as possible, we have to spot the problems as early as we can. This might come with having a good background knowledge of our students: of whose parents are going to have made sure their kids got to sleep by 10pm the night before and packed them off to school with oat bran and blueberry granola, and whose parents are going to let them stay up playing Fortnite till dawn and then send them out to greet the day with a can of Red Bull and a clip round the ear.

If we already suspect who the students are who may not be having their basic physiological needs met, then we probably need to get some fundamental interventions in place. This can be tricky, but regular reminders regarding the importance of sleep and eating breakfast will help. Try anything that might work. I once baked a loaf of bread for a child in my form when she told me that she only ever ate Haribos for breakfast. (I’m not sure it did much good; I have a sneaking suspicion she swapped it for some Tangfastics.)

Beyond physiological needs, students’ safety needs have to be met. This means that they should feel emotionally and physically safe within the classroom to have much chance of making any intellectual progress in lessons. This, too, can be a problem in the roiling emotional cauldron of the schoolyard. A student who’s being bullied or who’s worried about what might be awaiting them in the playground at breaktime is going to find it hard to concentrate on much else.

Similarly, too often a student is worried about something going on at home: a parent who’s ill, a sibling with depression, a friend with an eating disorder. The fundamental issue is that if a student is worrying about something, they may have little psychological or cognitive space left over for anything else. It’s hard enough for adults to be able to compartmentalise all the different things that might be floating around in their heads at any one time and still focus on their work, so it’s no wonder kids find it so tough.

I recall an incident with a student I had noticed using her phone in class, evidenced by the repeated surreptitious glances down in her lap every few seconds. I gave the standard warning, without a direct accusation, that if I saw anyone with a phone out in class I’d be obliged to confiscate it. She went back to work for about 30 seconds before she was drawn back to her phone. I had a quiet word with her, directly this time. She nodded in acquiescence, got back to work and I went back to my desk.

A minute later, there she was staring down into her lap again. This time I asked her to step outside the classroom. When I told her I’d have to take her phone, I could see the expression on her face run through a variety of emotions, none of them good. So I asked her, probably in that slightly sarcastic way teachers sometimes do, what was so important it couldn’t wait until breaktime.

It turned out that her older sister had tried to kill herself the previous night, and her mum was updating her from the hospital on her condition, which was far more important than learning why Henry VIII decided to break with the Catholic church. There was no way she was going to be thinking about her history lesson while also dealing with this, and it would be bizarre to insist that she did.

So I told her she could call her mum. After that, she came back to the class and I can’t say she did much work, but she didn’t need to use her phone again that lesson.

I know there’ll be some concern that if you let one student use a phone, however valid the reason, the floodgates will open and, before you know it, every kid in the class will be fielding calls from their distraught mothers. But I just don’t think that’s how it works. Kids tend to have a very heightened sense of fairness, and I’m sure most would recognise that the circumstances here were unusual and wouldn’t feel the need to demand the same treatment. The work’s important, sure, but it’s not always the most important thing there is.

Don’t bang your head

How do we try to overcome these issues? Obviously, you can’t just let students do nothing, or do whatever they like whenever they like, and you may not be able help very much with the problems they may face elsewhere. What you can do, if you suspect a student is having problems with their needs at the bottom of the pyramid, is to stop banging your head against a brick wall, trying to get them to complete another worksheet.

And you can try not to add to their troubles by giving them a hard time. And, just maybe, if you can squeeze it in with the other 30 kids in the room you’re looking after, and the learning walk that’s about to happen, you can grab a minute to ask them how things are and let them know you’re on their side.

It’s only what most teachers try to do all the time, of course: to create a supportive environment in the classrooms and show the students that they’re valued, although God knows that can be hard during last period on a rainy Wednesday.

It’s not an easy fix and it takes time. But, as Maslow points out, the rewards are significant and extend far beyond the classroom, not only creating students who are stronger and healthier but helping them develop personal responsibility and go on to “actively change the society in which they live”. That’s got to be a goal worth working towards.

In his later years, Maslow refined his theory to recognise that the hierarchy is not as rigid as he first assumed, and that one can make progress without necessarily passing through all the stages in order - although it will doubtless be more of a slog to do so. He also admitted that there were significant individual differences in how we managed progression up the hierarchy. Some people cope with unmet needs better than others. This is now what we refer to as having “resilience” or “grit”.

Maslow also points out that such are the drives to create and fulfil these deeper, more abstract needs that some people can achieve them even when their more basic needs remain unfulfilled - think of starving artists who keep working towards the elusive masterpiece or musicians who keep plugging away in pubs and clubs for nothing more than a free pint and a few tips.

And here lies a final way we can use Maslow’s ideas to help our students. If we can find what it is that will lead a student to the top of their own pyramid - the thing that drives them, the spark that ignites their educational fire - and we can help them to recognise this and work for it, it can allow them to overcome all manner of other disadvantages and obstacles.

As a teenager, Maslow had wanted to be a philosopher rather than a psychologist, but says he gave up after becoming frustrated “with all the talking that didn’t get anyplace”. Take note of his work on the hierarchy of needs, and you might save yourself and your students from the same frustrations.

Callum Jacobs is a supply teacher in the UK

This article originally appeared in the 20 March 2020 issue under the headline “Bare necessities”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters