Children in care turned away in their hour of need

“Children in care are among the most vulnerable in our society. We know that the vast majority have experienced abuse or neglect and therefore require additional support.”

They should be given the “highest priority” for school admissions.

These are not the words of a well-meaning social commentator. They are taken from a recent letter sent by schools minister Nick Gibb to England’s local authorities.

And they make it abundantly clear how strongly the government feels about ensuring that these children, above all others, have a place in school.

But a Tes investigation has uncovered worrying new figures showing that the reality for looked-after children is that they are often turned away.

The figures reveal that it can take nearly a year for children in care to be accepted at a mainstream school after applying during the academic year.

Almost a tenth of applications for in-year school admissions made on behalf of a child in care is not accepted within the statutory time frame of 20 working days, the findings show.

And applications to non-maintained schools - primarily academies - are half as likely to be accepted within the deadline as those to maintained schools.

England’s children’s commissioner and the virtual school heads who represent looked-after children’s interests blame schools and the pressures placed on them by government accountability measures. Meanwhile, lawyers say that the reasons given by schools for the rejection of looked-after children are often legally dubious.

But many of the schools involved claim that the areas that some children in care are sent to are not thought through, and that decisions by heads to turn them away are based on concerns for the child’s safety.

Whatever the truth, the findings of the Tes investigation are clear - vulnerable looked-after children are being denied a mainstream education for long periods of time, sometimes indefinitely. And this problem isn’t confined to just one or two areas: the freedom of information responses obtained by Tes from 50 local authorities indicate that similar patterns can be seen right across the country.

Missing out on vital stability

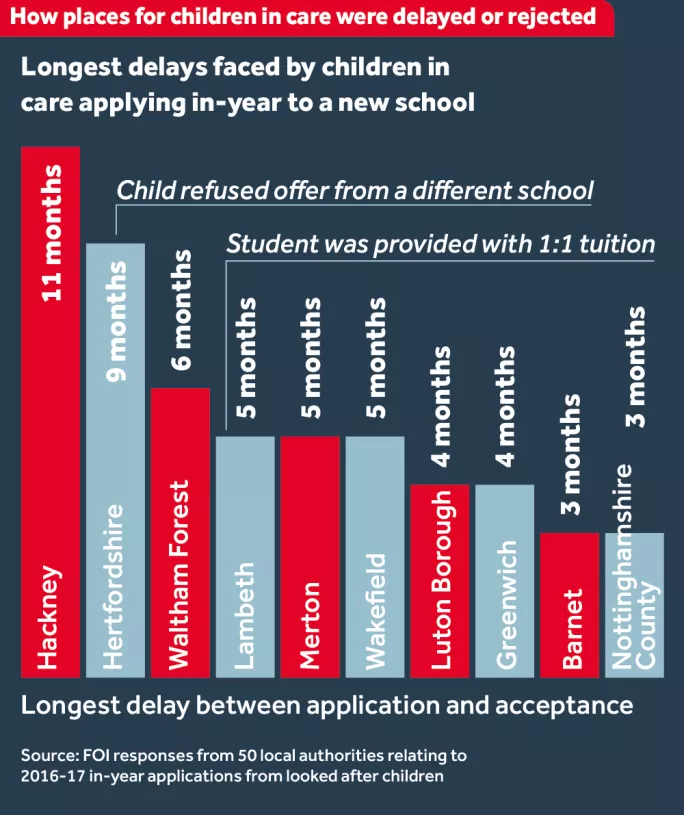

Hackney Council recorded the longest delay of 11 months for a looked-after child waiting for a school place. Nine other local authorities across the country admitted to delays of three months or more.

Not only do the findings appear to contradict Gibb’s message, but they also contrast with the statutory school admissions code, which makes it clear that looked-after children must be prioritised over everyone else.

Many of the delays in 2016-17 were down to schools initially rejecting applications, or simply failing to respond in a timely way, according to the FOI responses.

Help at Hand, a helpline run by the office of England’s children’s commissioner, has recently taken calls “where schools have drawn out the whole process in the hope that a child involved with social services will give up and look elsewhere”.

Being able to secure a timely move to a new school can be particularly important for looked-after children. Many will have been forced to move school during the academic year after being placed in care or after a foster placement has failed or because they are in such serious danger that they need to be relocated urgently.

So at a deeply unsettling time, the stability and routine offered by school can be vital. And, for a group who are behind their peers in every headline school performance measure, staying on top of classwork is essential.

However, many end up missing out on a full-time education while they wait for a school place, according to the National Association of Virtual School Heads (NAVSH), whose members oversee the education of looked-after children in their local authority area.

NAVSH’s immediate past chair, Alan Clifton, says: “They will usually be at [their foster] home, and they may have access to some online learning. But most foster [carers] aren’t paid to be at home during the day, so there might not be anyone from the foster home available to look after them.”

In this situation, it might fall to a social worker to keep the child occupied. “Some virtual schools will have some staff who might offer some teaching,” Clifton says. “But there’s no way that’s a full and balanced curriculum.”

Aside from the educational impact of being turned down by a school, looked-after children - who may already be struggling with feelings of rejection - can become “terribly depressed”, he adds. “The longer they’re out of school, the more they become disillusioned with what’s happening.”

And this rejection will often come at - or even precipitate - a very difficult time in their lives, judging by an Office of the Schools Adjudicator (OSA) report published this month. “For looked-after children, delays in securing a new school place when one is needed can have particularly serious consequences, including jeopardising a foster placement,” it states.

Blamed on ‘bureaucracy’

Why is this happening? Malcolm Trobe, deputy general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says some schools may struggle to add needy children to their roll at a time when funding for pastoral care and other provision is stretched.

“Local authorities and schools are very committed to ensuring that they meet the needs of every single child, but in order to do that they need appropriate, adequate resourcing,” he says.

The vast majority of children in care who require places are accepted by schools, Trobe adds.

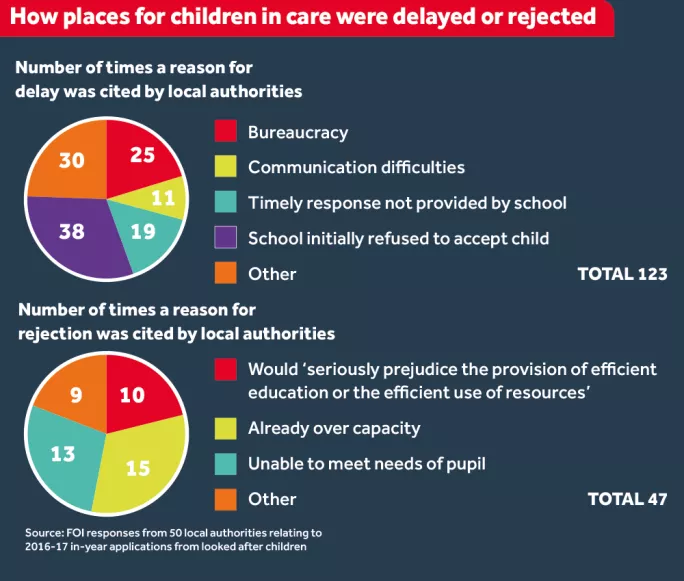

However, patently, this is not always the case. FOI responses show that on nearly a third (31 per cent) of the 123 occasions in 2016-17 when school places were secured only after the 20-day deadline - and for which local authorities provided an explanation - a school had initially refused to accept a pupil.

A fifth of delays were blamed by local authorities on “bureaucracy”, while in 15 per cent of cases, a school failed to respond to an application in a timely manner and in nearly one in 10 cases, there were “communication difficulties”.

Akin to ‘off-rolling’

The FOI responses also provide a detailed breakdown of the reasons why applications were rejected by schools. This shows that schools are frequently rejecting applications for reasons that are - according to a lawyer who has won cases on behalf of looked-after children - legally dubious.

For example, the most common reason given by schools for refusing a looked-after child was that they were already over their published admission number (PAN). But Dan Rosenberg, a solicitor at law firm Simpson Millar, says that there is “no indication” in the relevant legal documents - the School Standards and Framework Act and the School Admissions Code - that this is a good enough rationale.

The only acceptable reason, he says, is that admitting a child would “seriously prejudice the provision of efficient education or efficient use of resources”. And that, he says, is a “high bar” to prove.

But, like many aspects of the law, this appears to be a grey area. Richard Freeth, a partner on law firm Browne Jacobson’s education team, says: “It’s not a sufficient justification to be at or over PAN.

“But if you’re already 21 children over a PAN of 100, then you could argue it would also seriously prejudice the provision of efficient education or efficient use of resources.”

For children’s commissioner Anne Longfield, these rejections and delays are akin to the controversial practice of “off-rolling” - in which schools remove pupils who will detrimentally affect their performance measures.

“I’ve seen from our work on children who fall through the gaps in education that sometimes schools will remove vulnerable children in order to benefit the school rather than provide any benefit to the child,” she says.

“If schools are also denying a place to vulnerable children to begin with, that is also unacceptable and further damages the life chances of some of the most disadvantaged children in the country.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters