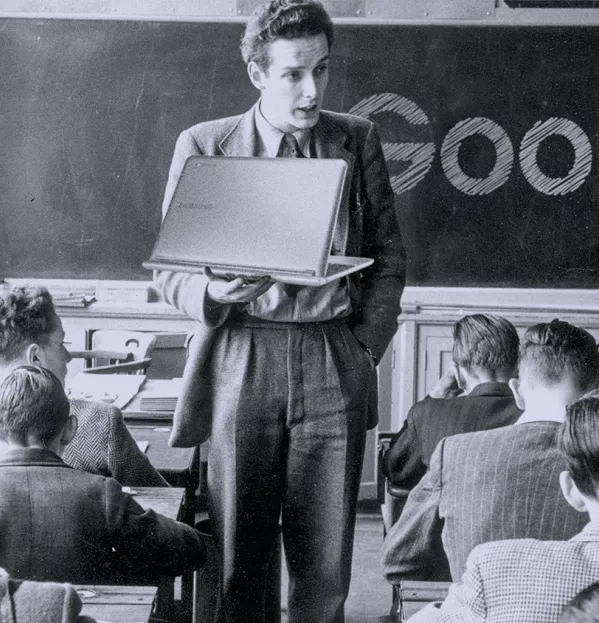

The Chrome age: Google goes back to school

Take a look around your classroom. Would you say it has been “googlified” yet?

If it hasn’t been, there’s a good chance it soon will be. Google has already conquered classrooms in the US. From almost no education footprint less than a decade ago, it is estimated that almost half the devices now shipped to American schools are Google Chromebooks and half of children in schools now use Google apps: predominantly its G Suite for Education tools, including Gmail, Drive and Docs, but also its Classroom tool that has feedback and homework applications. Now, tech experts and teachers think it could be about to repeat the trick in the UK.

The success of Google’s education enterprise in the US is certainly impressive. Since launching the Chromebook and G Suite in 2011, it has eaten away at the market share of Apple and Microsoft with its mix of free software (its apps) and low-cost hardware, (the Chromebook).

The trajectory in the UK has not been as sharp as that in the US. Data from analyst firm Futuresource Consulting indicates that Chromebooks accounted for 12 per cent of all mobile device unit sales into schools in 2016, from zero in 2012. Apple sales were 37 per cent and Windows mobile devices sales - ie, not including desktop machines - was at 47 per cent.

On the software side, Google says that it cannot break down users by country, but reveals it currently has 20 million users of Google Classroom worldwide and 70 million users of G Suite for Education. Microsoft did not reveal its figures for software, but so ubiquitous is Office 360 and Windows in schools that one would assume, safely, it is still way ahead of its rivals.

Mike Fisher, associate director of the education division at Futuresource Consulting, says that Google’s market share is likely to increase. “It is a well-packaged offering that resonates with teachers, IT and admin staff,” he says. But will it resonate enough for Google to become dominant?

Google-certified teachers

Google has been certainly smart about marketing its products in the US; it has rolled out the same successful approach here. It gets teachers to become its advocates by offering Google-certified status to those proficient in using its products and those who can train others or innovate using its products. The message: this is a product that teachers endorse, that they help to create and that they control.

Teachers tend to trust each other, not salespeople, so it’s likely that Google will get through the door of some schools because of this tactic.

With its G Suite for Education, Google Classroom and Chromebook, some teachers claim it has the tailored education products to persuade schools to make the switch.

Ian Addison, a Year 6 teacher and ICT leader at Federation of Riders Infant and Junior Schools in Havant, Hampshire, says it has transformed his classroom practice.

“It’s fantastic” he says. “When, for example, we did class presentations about Greece, I had the children working in teams of four, each with their own device. They were all working together, sharing information, collaborating and making notes. All the time, I was able to watch what they were doing and make comments and suggestions.”

Ben Foote, director of learning commons at Devonport High School for Boys, is also a fan: “When the Chromebook was released, it introduced a very low-cost solution to have quick access to all the required features [G Suite] that we needed.”

And you only have to log onto Twitter to read accounts of more and more teachers using Google Docs for collaborative working and other classroom tasks.

However, the statistics demonstrate that the converts to Google are still relatively few in number. That could be because of a number of issues. The first is that not everyone is convinced Google really does have its product offering right for the classrooms.

José Picardo, assistant principal of digital strategy at Surbiton High School, certainly thinks the Chromebook is problematic for teachers. “You have to have them open on the desk in front of the pupil almost as a barrier between them and the teacher, and that changes the dynamics of the lesson,” he says. “We were concerned it would not be a natural use of technology and setting up and booting up times could interrupt the flow of the lesson.”

He also feared that the presence of a keyboard on the device would be to the detriment of students.

“We didn’t want to reduce the amount of handwriting pupils do,” says Picardo. “As they are examined with handwritten answers, this is important. Lots of research also shows that people learn better writing than typing.”

Another potential issue for Google is price. Many schools say that they made the switch because of the low cost. Google’s head of education for EMEA, Liz Sproat, is more than happy to admit cost is a key factor in the rise of the Chromebook.

“As the demand for teacher and student devices increases, schools are increasingly in need of cost-effective devices that are easy to manage and meet budgetary restrictions,” she argues.

However, Google’s rivals claim they can be just as cost-effective. Ian Fordham, UK director of education for Microsoft, is bullish that Windows devices can more than hold their own - and price does matter.

“Choosing tech in school is always going to be a compromise of what’s needed versus cost,” argues Claire Lotriet, assistant headteacher at Henwick Primary School and Tes columnist.

If rivals can truly compete on cost, does that wipe out some of Google’s USP?

Then there is the issue of incumbent tech. It has been a fight in many schools to get teachers using technology at all. As a result, where technology has seeped in, there is a reluctance to switch from the first platforms that were adopted, as those schools that have attempted to convert to Google completely have found out.

Troubled conversions

“For a lot of classroom teachers, the thought of converting from PowerPoint was a big concern,” explains Lee Cross, from Leigh Academies Trust. “Theoretically it can be done, but we decided it would not be worth the bloodshed it would have caused if we had forced it on schools.”

The school now has a mixed approach to tech, with different companies providing tech for different uses. Both Lotriet and Picardo say that this is common. Google may be trying to cover all options, but most doubt that this is possible.

Finally, there are the concerns about privacy that have been expressed in the US. Some parents and commentators fear that Google could be monetising the data it collects and using its education products to hook children in to the brand for life. Google has denied those accusations in the US and Sproat reiterates the point.

“Let us be totally clear - we do not sell student G Suite data to third parties,” she says. “G Suite for Education is not funded by advertising and is an ad-free service. It is an enterprise product and is provided with a specific contract, in line with European data protection legislation, that governs how we use your data. Google does not own or manage the student’s data.”

Ultimately, it is careful consideration of the above points by teachers that should determine whether the tech giant does or does not repeat its US success in the UK.

But where Google is more likely to face the most problems is the polarised debate in the UK, where tech is often viewed as a homogenous beast - not the intricate web of different products it really is. Myth and rumour rule. This continues to hold back ed tech in general from progression in the UK - the debate is much less mature than in the US - and it may well be the thing that holds back Google, too.

Dan Watson is a technology journalist

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters