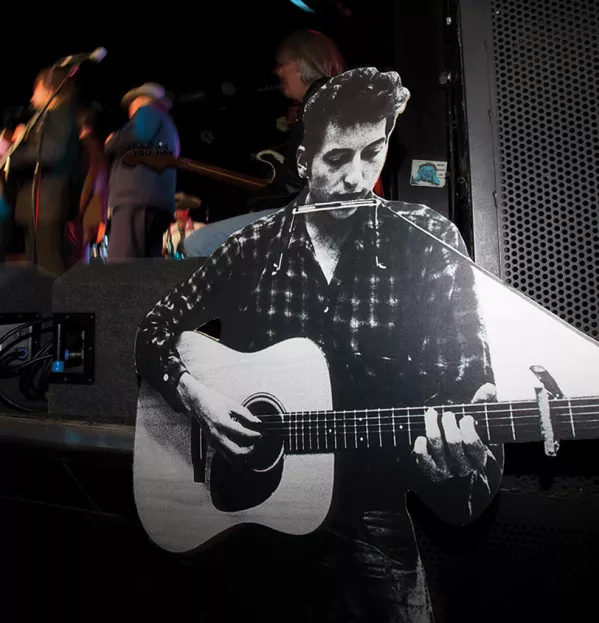

While studying Higher English, I had to write a critical essay - as pupils are still required to do to this day - on a novel, short story, poem or play. I asked if I could write about the lyrics of a Bob Dylan song, but I was told that this was hardly a work of literature and that I should “stick with Shakespeare”. Well, the poet Bob Dylan was recently awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Where are our former teachers when we want to reminisce?

Assignments and folio works dominate our National and Higher courses. One of the benefits on offer, to compensate for the considerable workload that they entail, is the freedom for pupils to research and write about topics they are particularly interested in.

In too many cases, however, pupils’ interests and enthusiasm are dampened by rigid guidelines and concerned teachers, who fear that the choice of esoteric topics may prevent young people from attaining the sort of marks that they are capable of achieving. Safe choices, and safe thinking, prevail.

Creativity is being squeezed in favour of formulaic ideas, often dictated by teachers or downloaded from the internet

Take the Star Trek fan who wanted to investigate the possibility of alien life in places where no one had ever travelled. The adventurous Trekkie was advised that such an endeavour might be too risky and was persuaded to join his class’s group investigation into the physics of effective seat belts. Then there was the impassioned young student who, quite unusually these days, had strong and interesting political opinions but was told he would have to keep those thoughts to himself.

Less clear-cut was the case of the 17-year-old pupil who wanted to write about her experience of losing her virginity for one of the folio pieces she had to complete in Higher English. The young lady was informed that the subject wasn’t appropriate.

Creativity is being squeezed in favour of formulaic ideas, often dictated by teachers or downloaded from the internet. Marking schemes offer little incentive for originality and creativity. In one subject, many pupils follow a 20-point plan showing how each of the 20 marks can be earned.

Instructing pupils on what to write, and how to write it, defeats the whole purpose of assignments and folios. There is so much more to be gained by encouraging freedom of thought and expression. Risk-takers with imagination, and a willingness to think outside the box, are the people most likely to succeed in the 21st century.

I commend a colleague who encourages her pupils to write essays that have never been written before. I am also happy to endorse the astute words of the winner of the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature: “Don’t follow leaders, watch the parkin’ meters.”

John Greenlees is a secondary teacher in Scotland