EAL pupils’ table-topping GCSE results: miracle or mirage?

When the government published its GCSE statistics earlier this year, the data showed something quite extraordinary. In 2017, for the first time ever, students with the apparent disadvantage of having English as an additional language (EAL) outperformed native speakers on all of the Department for Education’s key measures.

The news prompted celebration, with people hailing the educational achievement of pupils from communities that have often been marginalised. But it also raised a whole host of questions: what lies behind this remarkable performance? Is it because immigrant groups are more aspirational? Are the bonds stronger between these communities, parents and local schools? Does speaking two languages bring wider educational benefits, or is the strong performance of EAL learners just a quirk of geography that reflects a “London effect”?

Sceptical voices are questioning whether the statistics are distorted by missing data and methodological problems. There is a risk that rosy-but-inaccurate figures could breed an unhelpful complacency towards pupils who still require significant support. But perhaps the most serious charge - levelled by a group of headteachers in the North West - is that the government’s key performance measure, Progress 8, gives an advantage to schools with a high proportion of EAL students, while penalising those serving white working-class communities. Clearly, then, there’s a pressing need to better understand the EAL figures.

What made the 2017 GCSE statistics so striking was the strong showing by EAL students across all of the main performance measures. The average Attainment 8 score for EAL students was 46.8; for those with English as a first language, it was 46.3. For Progress 8, the gap was much bigger - EAL students scored 0.50 compared with -0.11 for their native-speaking peers.

The strong performance continued across the English Baccalaureate. The percentage of EAL students entering and achieving the EBacc was 45.5 per cent and 24.2 per cent respectively, compared with 36.9 per cent and 20.8 per cent for native speakers.

The idea that there is something noteworthy going on in the UK regarding the education of pupils from immigrant backgrounds appeared to be confirmed by research published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) last month. The OECD’s study was based on data from the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) survey, which explored the performance of 15-year-olds across maths, reading and science. While the study did not find that UK pupils with an immigrant background outperformed their native-born peers, it said the gap in performance was smaller than in other economically developed countries.

In Pisa 2015, 73 per cent of pupils born in the UK, along with 67 per cent of immigrant pupils, attained at least the basic proficiency level 2 in the three Pisa subjects. This 6 percentage-point difference was significantly smaller than the OECD average of 18 percentage points.

‘Extraordinarily high expectations’

So what is behind the high performance of students from an immigrant background in Britain? A common suggestion is that their families are simply more aspirational. This view has some high-profile adherents. Michael Gove, the former education secretary, has said that many immigrant parents have “extraordinarily high expectations” for their children.

“Some of the most demanding parents and some of the most involved parents are those who…might be refugees from Somalia or Kosovo, but they want their children to succeed,” he said. “They have very, very high expectations of the school.”

While many immigrant families may be very driven, it seems unlikely that this is the sole explanation. If aspiration is simply intrinsic to immigrant communities, then why is there such international variance in the attainment of pupils from these groups (see graphic, above)?

Sam Freedman, an executive director of Teach First, suggests something more subtle is going on. Writing for Tes earlier this year, he posited that the answer lies in “the interactions between families, schools and communities”. Freedman highlighted the example of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, in which, after a period of educational underperformance, “the local authority and headteachers worked hand-in-hand with community leaders and parents to change attitudes and build trust”. He suggested such cooperation between schools and families may be challenging in more atomised white working-class neighbourhoods.

Geography could also be playing a part. A significant proportion of EAL pupils live in London, and the capital has seen its educational performance climb in recent years. The capital has been at the centre of a number of policy innovations, including the London Challenge, Teach First and the sponsored academy project.

But, back in 2014, Simon Burgess from the University of Bristol found that the opposite was true, and that London’s strong performance actually seemed to be driven by its pupil demographics - namely, the city’s higher proportion of children with an immigrant background. According to the professor’s research, if London had the same ethnic composition as the rest of England, there would be no “London effect”. He also found no significant difference between the progress of white British pupils in London and the rest of the country.

An alternative explanation to the EAL conundrum is that speaking more than one language has wider learning benefits. A study into the effects of language learning by academics from the UCL Institute of Education in February pointed to the cross-curriculum benefits of language learning.

The study questioned 740 people - mostly adults working in education - and found that almost all were in agreement that learning another language helped analytical and multitasking skills, as well as memory, focus and creativity. Most of those surveyed agreed that learning a new language helped with learning other things.

However, there is a counternarrative to all of this: some people think the appearance of an EAL “miracle” is actually the result of missing data and methodological quirks. A report by the Education Policy Institute (EPI), published earlier this year, highlights the fact that many EAL children are missing attainment data because they arrive at school after the time of the assessment. The thinktank estimates that about three in 10 children with EAL fall into this category in primary schools, and about one in 10 in secondary schools. If these children were included in the data, then the results could look very different.

A more fundamental objection is that our current accountability system could in some respects inflate the performance of children with EAL. Under Progress 8, schools are judged on how much progress their students make between a key stage 2 baseline at the end of primary school and GCSEs at age 16.

Diversity ‘masked’

But the EPI notes that the whole idea of academic progress is “confounded by English proficiency for children with EAL”. Assessments undertaken before a child is proficient in English will naturally underestimate their academic attainment. This means that when they are retested in secondary school at a time when their English is much improved, they will appear to have made enormous progress. Heads running schools with a small or non-existent cohort of EAL pupils find this aspect of our accountability system particularly troubling.

The great danger, of course, is that the way in which we measure student performance could end up telling us a misleadingly optimistic story about how well we are educating EAL children. This could in turn cause schools and the government to take their foot off the gas.

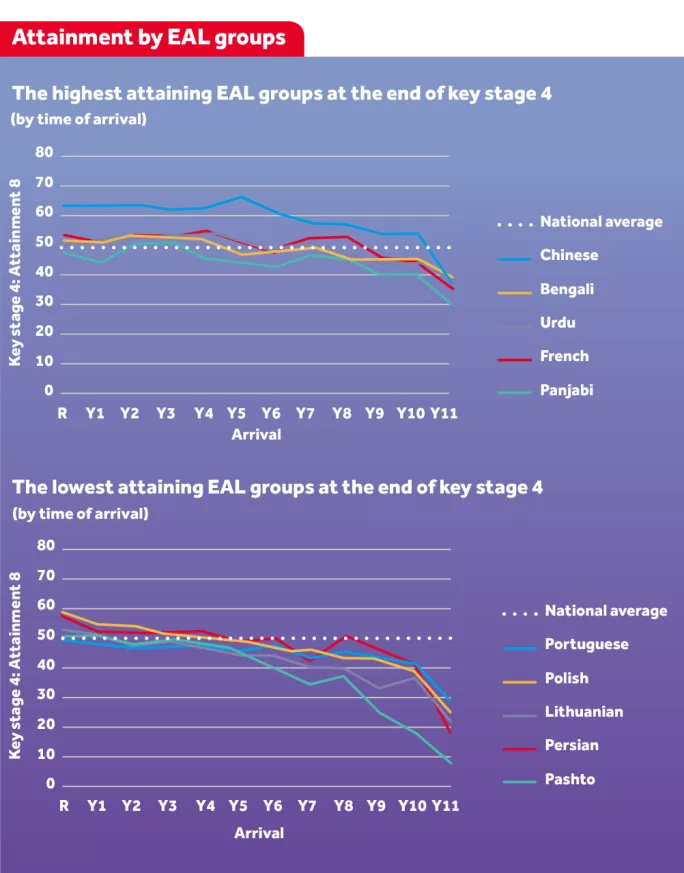

The fact of the matter is that the term EAL covers - and masks - an extremely diverse group of children with attainment varying widely based on a child’s first language and how late they enter the school system. The EPI finds that pupils with Chinese as their first language have above-average Attainment 8 scores at age 16, even if they have arrived as late as Year 10. But pupils with Portuguese as their first language have below-average attainment, even if they have attended English schools since the age of five.

So is the performance of EAL pupils in England a miracle or a mirage? The truth is probably that because of a complex mix of social, cultural and economic factors, children from some immigrant backgrounds generally perform very well, while others perform less strongly. It’s a complicated picture that is further fogged by imperfect data and measurement systems.

Teachers and schools should be applauded for the hard work they do every day with EAL pupils. But our system could benefit from more detailed performance statistics, such as breakdowns by first language and time of arrival in English schools. Only then will we have the confidence to say that vulnerable children are not being left behind.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters