The exam system? It’s all Greek to me

My tutee, Sebastien, sits on the orange plastic chair in front of me. He is 14 and something is troubling him. “So, what’s wrong, Seb?” I ask. He shrugs. But his is no ordinary teenage shrug: Sebastien’s parents are French and, even at 14, his shrugs are heavy with existential significance.

There is a pause. He is weighing up how to tell me something I need to know. “The thing is…”, he falters. “The thing about learning is…”

“Yes?”, I say, encouragingly.

“Well, I’ve just realised that it’s a bit pointless, really, because the more I learn, the more I realise I don’t know.”

In the film version of my life - the one in which I am played by George Clooney and my wife says, as we leave the premiere, “it’s a pity George isn’t as good looking as you” - I stand and turn to a groaning bookshelf in my study (the scene in which this conversation is taking place has Sebastien seated in a leather armchair in front of a crackling fire). I pull out an impressive tome and, translating from the Ancient Greek as I go, I turn and say gravely to Sebastien: “Plato tells us that the great Socrates himself put it thus: the only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.”

But this is not the film version of my life. I am not George Clooney; Sebastien and I are sitting on wobbly plastic chairs in a dingy classroom; I can’t read Ancient Greek, let alone translate it; and what I actually say is something like: “Everyone gets a bit down at this time of the year, Seb, so don’t worry. Cheer up - it’ll soon be Christmas.”

Without his knowing it and my realising it, Sebastien has nailed the Socratic paradox. Not only does he have the shrug of a French philosopher, he holds the wisdom of the ancients. He has, indeed, demonstrated the pointlessness of most learning in school, not in the way he thinks he has but in the way that he actually thinks.

For Sebastien has seen through the veil of the school curriculum and perceived something of the limitless human learning that lies behind it. In doing so, he has realised that he will only ever grasp the tiniest scintilla of all that learning and his despair is born of his realisation. It is as if he has experienced the intellectual equivalent of the Total Perspective Vortex in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Fortunately, Sebastien survived the trauma of his adolescent aperçu, went on to do well in his exams and qualified as a doctor. I am sure he has made a great medic: creative, thoughtful and humane.

My response to Sebastien was inadequate to the moment but at least I kept the truth from him. I didn’t tell him then just how little the rest of his school education would encourage him to explore the profundities that he had glimpsed, or just how little his evident capacity for original thought would be valued in the examinations that would be the key to his future.

I taught him English as well as being his personal tutor. How much worse it would have been to tell him that - for all my enthusing about the importance of wider reading and developing a personal engagement with the text, for all my incorporating drama techniques into my lessons and insisting that we went on regular visits to the theatre, and went to hear poets reading their work - the best effort-to-examination-grade ratio would almost certainly be achieved by doing none of that.

“Don’t worry about what you don’t know, Seb,” I perhaps should have said. “Learn that page of quotes from Of Mice and Men and remember what I’ve told you to say about Lenny and those rabbits. Do that and you’ll be fine.”

‘I never channelled Socrates’

But I was never very much good at promoting “strategic learning”, as it came to be called. Even today, I have been known to tease my colleagues in school by saying things like, “none of my most valuable experiences at school happened in the classroom” - which is mostly true.

What is certainly true is that very few of the intellectual interests that sustained me through school and university, and which remain with me in adult life, derived from learning for exams. And it wasn’t even as if I was the kind of 14-year-old who channelled Socrates without realising it.

I think I can identify when, in England at least, “strategic learning” captured the education system.

In the 1990s, I was a head of English and corresponded every year with our coursework moderator, who lived near Porlock in Somerset. Unlike Coleridge’s original, this “person from Porlock” was no hindrance to my work. Indeed, he became a sounding board, a benign taskmaster and a mentor, unseen but appreciated nonetheless.

We sent him our pupils’ portfolios and he sent back notes handwritten on Basildon Bond paper, saying things like, “I’ve never read Gillian Clarke before, but now I’ve read the poems your candidate wrote about, I certainly want to read more”. Even when he was disappointed, he was supportive: “Overall, the standard this year was weaker than last but I can still tell that they’ve been taught by a crack team of enthusiasts,” I recall him writing once.

Then, one year, instead of a handwritten letter, we received an indecipherable computer printout. No explanation, no feedback. Regretfully, my colleagues now referred to the “non-person of Porlock”, and we imagined him airbrushed out of existence by the exam board for the crime of being excited by the journey of learning on which our pupils had embarked.

My complaints about the soullessness of the new processes had brought only a standard response, citing the requirements of fairness and rigour. But increasingly, in the years that followed, moderated marks varied wildly.

We noticed that when some portfolios were returned, the brief comments from the moderator betrayed a lack of sympathy with candidates’ ambition. Sometimes, they simply betrayed a lack of understanding of the texts they had chosen. Little by little, we felt obliged to advise candidates to be cautious and predictable in what they wrote. Little by little, the “crack team of enthusiasts” became less enthusiastic. But grades went up most years, so that was the main thing.

Much has changed in the intervening decades, but I am not sure much has progressed. People who defend the current state of exam systems across the UK say that exams achieve fairness and rigour. And they are right, in a sense - but it does depend on what you mean by “fairness” and “rigour”.

If “fairness” means that candidates get grades that correspond to their abilities and performance, it would have been very dubious to claim that exams were fair even before the crises of summer 2020. Some recent data in England suggests that 10-15 per cent of candidates underperform simply because they have “a bad day”.

Other research sponsored by the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference had already suggested that some 25 per cent of GCSE grades were wrong. So, in England, fairness does not mean candidates getting results according to their abilities, then. And where is the evidence that it is any better in Scotland or elsewhere in the UK?

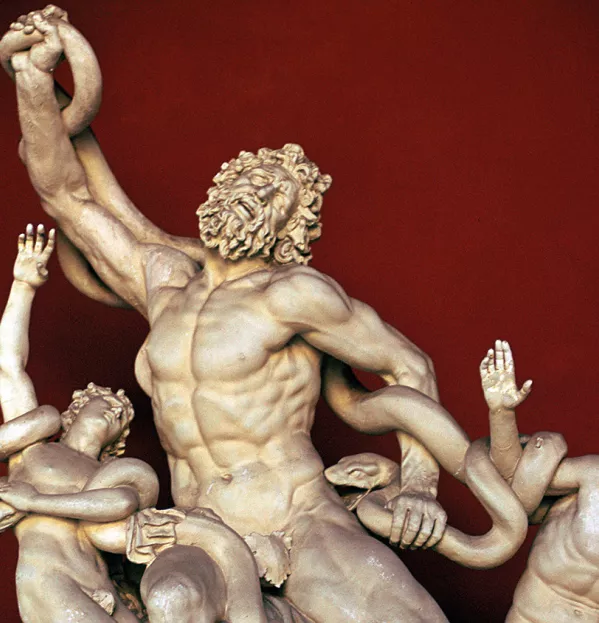

And rigour? Well, if rigour means writing predictable answers based on predictable questions using predictable turns of phrase and a predictable framework, then our exam system is a model of rigour. But it’s the rigour more of Gradgrind than Socrates.

And, as Scotland’s International Council of Educational Advisors (ICEA) wrote in its December 2020 report: “The capacity to apply learning creatively in unfamiliar contexts is increasingly the kind of high-value skill demanded by the workplace of the future. Traditional examinations are not capable of making such assessments on their own”.

In many subjects, there is a fairly brutal trade-off between fairness and real rigour. In order to minimise marking errors, you must reduce the scope for personal interpretation of a mark scheme. But in doing that, you also reduce (or even eliminate) the scope for an examiner to evaluate the personal response that is the very point of a candidate studying the arts and humanities. And you therefore place a premium on teaching strategies that maximise compliance with the terms of the mark scheme rather than extending knowledge and understanding beyond it. There are no marks for being too clever.

Not that there is any absolute guarantee that grades awarded in supposedly more objective subjects, such as mathematics and the sciences, are correct, let alone reflect the innate ability of candidates.

The exam room is inherently unreliable in testing anything other than timekeeping, concentration, handwriting and the ability to stay silent for long periods of time.

These may be useful skills in themselves, and arguably they are analogues for more educationally valuable attributes.

However, the focus on factual recall and the fast-paced sense of anxiety of our current examination system makes it feel like a bizarre cross between Kim’s Game and the Cresta Run. Both of those activities are worthy and require undoubted skill and ability, but you wouldn’t put them together and claim that they gave you a particular insight into the intellectual capacities of a 17-year-old.

It remains to be seen whether we will see a post-Covid end to what the ICEA calls the “one-time sit-down high school examination” and whether latter-day people from Porlock to Perth, Peebles and Portree emerge from their non-personhood to help develop what the ICEA described as the “greater role for internal assessment in determining qualifications that better match the knowledge and skills demanded by wider social and economic change”.

I hope a “greater role for internal assessment” does mean a greater role for coursework, but two important questions must be addressed. First, how to avoid the wasteful consumption of teachers’ and pupils’ time on assessment rather than learning. The classroom must remain a workshop where mistakes can be made, not become a showroom where only the perfect is acceptable.

And second, what about equity? The argument goes that a boy from a socially disadvantaged background with no access to the internet can perform as well in a sit-down examination as a girl from a well-off home with a graduate stay-at-home mum who would happily do her coursework for her.

Pre-packaged knowledge

Maybe traditional exams can provide something like the socially level assessment playing field of myth. But surely it is to massively misunderstand and underestimate the causes of educational disadvantage to think that this is an unanswerable argument in favour of their primacy in our system.

It is depressing that we continue to find reasons to be satisfied with the safe method and the predictable outcome.

Many of those reasons are honourable in themselves but they nevertheless let children and young people down.

An assessment regime that merely rewards pupils for being successful strategic learners will never enable them to be confident or responsible citizens of the intellectual world beyond the scope of our current knowledge, let alone effective contributors to the development of the future that they must shape in order to inhabit. But better assessments, in whatever form, will not help either unless they are seen as tools of the craft of teaching rather than the main objective of the system itself.

I wish we had the courage to embrace the infinite possibilities of human learning that Sebastien glimpsed all those years ago. For us, there need be no crisis of confidence. We can do this. We must do this. We can no longer risk our children and young people simply being consumers of pre-packaged knowledge. We desperately need them to know that learning in every discipline is a creative process and that creativity, by its nature, has no limits to what it can achieve. That should be our only strategy.

Melvyn Roffe is principal at George Watson’s College in Edinburgh

This article originally appeared in the 5 February 2021

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters