GCSEs 2021: Don’t blame teachers for this free for all

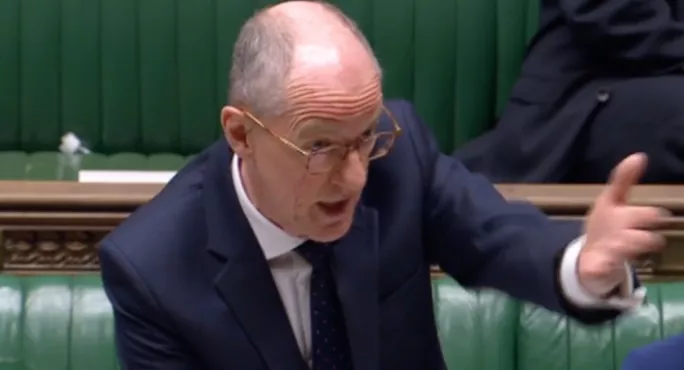

If Nick Gibb sounded a little hesitant at times last month as he did the media rounds to sell the government’s approach to grading this year’s GCSEs and A levels, he could hardly be blamed.

Last August, the schools minister had defended the use of an algorithm for the 2020 results, warning that using teacher assessed grades without moderation “would be misguided and create deep inequities”.

Not only that, but: “Without moderation, there would be grade inflation of 12 percentage points at A* and A, casting doubt on the validity of these grades in the eyes of employers and universities.”

“There would also be severe disparities between schools,” he had continued. “The teachers and schools that had done their best to follow the rules and guidance in awarding grades would see their students at a disadvantage, compared to those which had been more lenient. This is simply not fair.”

Now that unhappy vision is about to come true as a result of his government’s say so. There will be teacher-assessed grades this year, but there will be no exam board and Ofqual moderation in the usual sense, no algorithm to keep grading in line with previous years.

GCSEs 2021: The 5 big problems in Ofqual’s grading plan

GCSEs 2021: Silence on the biggest injustice of all

In full: GCSE and A level 2021 Ofqual and DfE proposals

GCSEs 2021: 4 reasons why more unfairness is inevitable

In full: Williamson’s letter to Ofqual on GCSEs and A levels

Many teachers have welcomed this news. But the danger, as some have already warned, is that it is teachers who will be held responsible for the inevitable mess that will follow. It is teachers who are being expected to make this flawed system work.

Mr Gibb, who is due to face questions from MPs on this issue this morning, has said that his government trusts their judgement because “they are the people that know their pupils best”.

Gaping hole in GCSE and A-level teacher grading framework

But the truth is teachers are not being given all the tools they need to do the job. So far, there is a gaping hole in the framework they are given being to work out what GCSE and A-level grades their students should get this year.

The problem is that it does not look like they will be told what standard they should set grades at. Ofqual chief regulator Simon Lebus has said that “quality assurance arrangements” will expect that teachers “look at performance in prior years” and will expect them to provide an explanation if the grades they come up with are “wildly out of sync” with previous years.

But so far no one has specified what exactly they mean by “prior years”. Do they mean last year when the moderating algorithm was ditched and Mr Gibb’s prediction came true - there was huge grade inflation? Or do they mean the years before, when the “comparable outcomes” algorithm approach kept grades broadly constant at a much lower level?

There is a huge difference between the two and, to date, teachers have been given no guidance on which side they should come down on. But at the same time, it is teachers who are being expected to take responsibility for making sure that the resulting grades are credible.

Ofqual not expecting ‘huge’ grade inflation

In words that may come back to haunt him, Ofqual’s chief regulator, Simon Lebus, said last month that he does not expect grades to go up much in 2021.

“There was a lot of grade inflation last year,” he told BBC Radio 4. “I am not expecting there is going to be a huge amount this year because we are adopting a completely different approach.”

But even if there is much clearer guidance about where standards should lie, that seems fanciful. Ofqual and ministers have set huge store in the “quality assurance” system they are introducing this year. But most of that quality assurance will be internal, within schools.

Exam boards will only be conducting spot checks and those checks are not supposed to be about maintaining a standard, not in the usual sense anyway. “Changes to teachers’ grades should be the exception and will only be if the grade could not legitimately have been given based on the evidence,” Ofqual and the DfE have said.

Pressure on teachers to push GCSE grades upwards

So it will all be on teachers. And teachers will inevitably be facing several huge pressures to push grades further upwards.

The first one is that, even though Ofqual and ministers do not seem prepared to come out, take responsibility, and say it, 2020 must inevitably be their benchmark.

What fair-minded teacher would look at this year’s cohort with all the disruption and difficulties they have suffered and then decide that they should also be graded to a tougher standard than last year?

The second point is that teachers will also know that, as there is no moderating algorithm to counter grade inflation, teacher grades are likely to stand. They will know that their colleagues in some schools are likely to want to be as generous as possible and they will not want their students to lose out by comparison. So there will be a natural inbuilt propensity to push grades ever upwards.

And it seems it is teachers who will be the fall guys when inflation rockets. “We are trying to give teachers the opportunity and the flexibility to exercise their judgment in a responsible way,” Mr Lebus said last month.

Of course, Ofqual and the DfE could yet come out and give teachers more of a steer about where standards should lie - pre- or post-2020. Mr Gibb could say something when he faces MPs today or there could be something more definite in the guidance eventually published by exam boards.

But the signs are not good. The vagueness over where grades should be set sounds like it is the result of a deliberate political decision to avoid any association with the word “algorithm” that became so toxic last year.

As education secretary Gavin Williamson told Parliament last month: “We didn’t feel as if it would be possible to peg [grading standards] to a certain year because, sadly, as a result of doing that it would probably entail the use of some form of algorithm in order to be best able to deliver that.”

That decision may spare his political blushes in the short term. But, as his schools minister has already said, it could have serious repercussions for the longer term “validity” of the exams system.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.