Governors look after pupils, not government policy

It’s easy not to notice just how much your child’s primary school can become a part of your life. The attachment creeps up on you: the familiar walk, the smiling faces, the “good mornings”, the kiss goodbye, the chat in the playground, queuing for a performance, going into class, the Christmas fair, the school concerts and so on.

I’ve been in my daughters’ classes for lessons, I’ve watched music recitals, I’ve run the dads’ race on sports’ day, I’ve been to countless parents’ evenings, I’ve dashed forgotten PE kits and lunches to the school office. I’ve seen one daughter go from the first day of Reception to the last day of Year 6 and have another who is not far off. It’s part of the fabric of my life and has been for a decade.

Many of my governor colleagues feel the same - and there are some more fecund types who have been doing it even longer than me. So while we, the school governors, are not in the classroom actively changing young lives, we are in the background trying desperately to create the conditions in which this can happen at the school we know and love. For us, every child matters, as the phrase goes. And I mean “every child” - even the little buggers...in fact, especially the little buggers. We know that for some children, school is a place of refuge, certainty, warmth and hope: we cannot let them down.

When I wrote an article for Tes in February on the complexity and weight of a governing body’s decision over a) whether to become an academy; and b) whether to join a multi-academy trust, it was essentially a hypothetical musing. The article’s final three words were “should we jump?”: a question that wasn’t being asked only by us but was troubling governors in thousands of schools facing a similar conundrum. Although the responsibilities of governors have always been more onerous than most people realise, this decision takes it up another level.

In September’s survey report, produced by the National Governance Association (NGA) in partnership with Tes, it was revealed that 40 per cent of governing boards have two or more vacancies and that it is becoming harder and harder to recruit. While recent drives to raise the professionalism and increase the training of governors, as well as focusing on skills-based recruitment, are of course positive things, they are also part of a reconceptualising of governors that can make the job seem a little forbidding from the outside. And once you do become a governor, the management of a dwindling budget and increasing costs falls at your door; the teachers’ and teaching assistants’ P45s are approved by your votes, the once-in-a-lifetime decision over whether to become a MAT is down to you.

Perhaps former Ofsted chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw wasn’t wrong when he said in 2015: “The role is so important that amateurish governance will no longer do. Good will and good intentions will only go so far. Governing bodies made up of people who are not properly trained and who do not understand the importance of their role are not fit for purpose in the modern and complex educational landscape.”

As subtle as a sledgehammer maybe, but worthy of consideration. (He also advocated paying governors, which I think was a misjudgement. The NGA survey figures reflect the consensus, I think, that we overwhelmingly do this to make a difference, not to get paid: that would change the school-governor covenant completely.)

Around the time I wrote the article in February, we began to have discussions with a MAT and all the questions and arguments rehearsed in those discussions were buzzing around my and my governor colleagues’ heads. The particular sense of our decision being monumental, of leading our school on a journey with no reverse, was palpable. Our responsibility to the children, teachers, parents and community both now and into the future had never weighed more heavily.

However, our particular situation demanded that a decision be made and it was not just a matter of principle on which we had to make it but on a genuinely practical set of circumstances that demanded we ask ourselves: “What is the very best decision for the children in our school now and into the future?”

Weighty responsibility

While we took on this enormous decision with the gravity it demanded, there was also something slightly surreal about it. Here, sat in the staffroom on a Tuesday evening, were a group of people, most of whom had never even worked in education, many elected by the votes of parents in low-turnout elections, all volunteers fitting in school governance around their jobs and family. Suddenly, we were being asked to make a decision about our school that set its direction for decades to come, modified its public sector status and potentially had an impact on tens of thousands of children’s education.

It was perhaps a function of the weight of this responsibility that led us to interrogate this issue to an extraordinarily deep level. What we realised after our months of exploration was that we would actually never feel 100 per cent certain of this decision and there had to come a time when we had investigated, questioned and conjectured all we could.

As governors, we had revisited the issue regularly over recent years but we were a “good” school with good results and happy children and we remained ambitious for more. We’d done this as a maintained school and had found no compelling reason to change.

However, when Spencer Academies Trust (SAT), which had already taken over the secondary school into which we feed, was then awarded the right to run the new primary school in our village, it would have been a dereliction of our duty not to find out more.

This, of course, is where the personal and the practical have to overtake the principle. Do I feel the academy project is the answer to all our education dreams? Nope. Have academies across the country covered themselves in glory in recent years? No. Do I think academisation and competition is a better way to raise educational standards than investing in all schools sufficiently to ensure a high standard for every single child, no matter where they live? No, I don’t. (Equally, I recognise that many academies have done extraordinarily positive things and the vast majority are simply trying to work within the current system - and with essentially the same inadequate funding - to deliver the very best possible outcomes for children.)

As a governor of this school, do any of these principles really matter? Not really. Because the principle that casts all others into shadow is a school governing board’s obligation to its children now and in the future. It is not my job to like or dislike certain policies, it is my job to respond to them as best I can for the benefit of the school. For us not to have looked at this opportunity because we wanted to adhere to a political principle would have been a textbook example of cutting off our nose to spite our face.

More practically, it felt to us that when it came to academisation, it was not a matter of “if” but “when”. I know the discourse has shifted a little in recent times but the road from soundbite to passing a bill in Parliament is a long one, littered with casualties.

Foresight, not hindsight

We didn’t want to convert for the sake of it but, equally, we did not want to be late to the party and be forced into a decision we didn’t want to take. For the want of some boldness and ambition, I didn’t want to be standing in front of parents in five years’ time, using the politicians’ favourite excuse: “Hindsight is a wonderful thing...”

So we did our homework: we spoke to all the local MATs, we received a couple of detailed proposals to join from those whose vision matched ours, but it became clear that SAT was presenting us with some unique opportunities, centred around our school’s strong links to the secondary school and to the forthcoming second primary in the village.

So we spoke - freely and frankly - to schools who had joined SAT, and we came away very impressed. They had all retained their individual identities and much of their autonomy.

It’s interesting that the NGA report notes a distinct slowing in the direction of travel towards more academy conversions. The majority of governors not in a MAT are not currently considering this option. The report says: “It is encouraging to see that the majority of governing boards are considering the options available and making the choices they believe best serve the interests of children in their community. It also reflects a lack of clear direction from central government.”

Indeed it does. And that lack of clear direction further muddies the waters for those governors desperately trying to make the right decision for the school.

Our school, Hilton Primary, has always been at the heart of the village community. When the building of a new school was announced, it was a real concern to us that we would no longer be able to offer the shared village school experience in the same way (although a relief that we would be able to stop adding temporary classrooms to the playing fields and needing a degree in logistics to get 850 children through lunch in 75 minutes). It felt like the end of an era. But by joining this particular trust, we could see an opportunity for the two primary schools serving Hilton to work closely together so that the children and staff could develop together.

When you have 850 children in a school, from a village population of around 8,000, the school necessarily plays a central role in community life. The community and parents alike trust the school - and by definition the governing board - to get things right. Friends of mine have said directly to me: “I don’t quite know how being a governor works, but I trust you to make the right decisions for our kids.” This is both gratifying and disquieting. It’s a reminder that this role is never just about dealing with the school as an organisation, it is far more personal than that: it is about the community’s children, my friends’ children, my children. I don’t want to disappoint anyone.

Farewell to all that

The curious thing is that by making a decision in favour of becoming an academy, we volunteer to be emasculated somewhat, to be stripped of our legal rights and responsibilities.

The legal entity becomes the MAT, not the school. I have therefore been on my last headteacher appointment panel and my last pay committee. I have heard my last formal complaint. I have signed off my last budget. And this is not a time-limited situation: this decision stands for good.

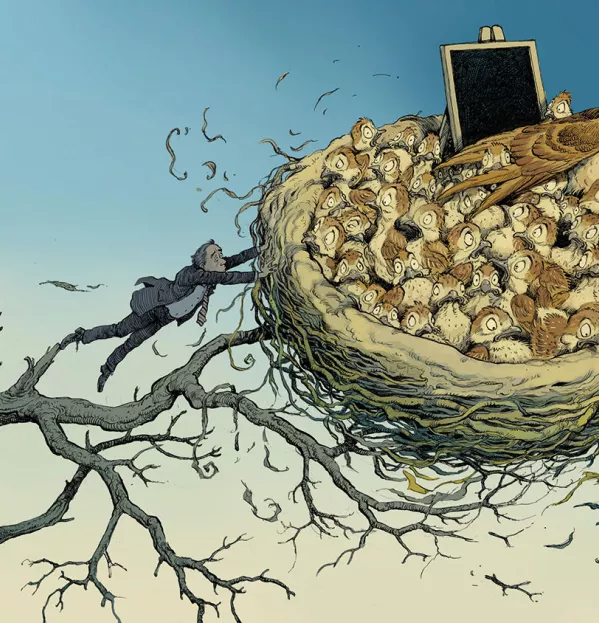

It’s hard not to feel like we’ve fed and nurtured this baby for years, nursed it through the hard times, shared the joy of its blossoming, and now we’re handing over the reins to its new family before it’s fully grown. Currently, we’ve still got custody (in practical terms, we become the local governing board operating in largely the same way as before) but legally we’re no longer in charge.

The bottom line is, this decision is only the right one if it presents new opportunities for our children that would not otherwise have been possible. The decision, one way or another, had to be made by us, this merry band of mums, dads, staff and servants of the community. We asked all the questions we could and we sought - and received - all the assurances that we could. At some point in this process, the talking had to stop and we had to take a leap of faith. That point is now.

Nick Campion is co-vice chair of governors at Hilton Primary School, Derbyshire. The school became an academy and part of Spencer Academies Trust on 1 October

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters